|

More than ten years after the last review, the College Council

voted on March 10 to revise the undergraduate curriculum.

To be implemented in October 1999 for the Class of 2003 and beyond,

the new curriculum will divide undergraduate coursework into thirds:

the Common Core, a concentration, and free electives. Previously,

the Core made up half the coursework, with the re-mainder split

between the concentration and electives.

|

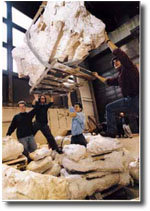

| Twenty-five

tons of dinosaur bones arrived on campus in February,

courtesy of U of C paleontologist Paul Sereno (in light

blue shirt) and a research team that included (from left)

College student Noel Heim and graduate students Hans Larsson,

SM’96, and Jeff Wilson. Found in the Sahara Desert during

the team’s four-month 1997 expedition, the bones comprise

several skeletons, including a new species of sauropod. |

|

Dean of the College John Boyer, AM’69, PhD’75, broached a

curricular review when he took office in 1992. Beginning with

a series of retreats with faculty from the collegiate divisions,

he next organized a College-wide faculty retreat in December

1995. In January 1996, Boyer then commissioned the “Friday

Group” to study the College curriculum.

Named for its meeting day, the Friday Group consisted of

the five collegiate masters, the seven members of the Committee

of the College Council, and the eight members of the College

Curriculum Committee. The group met throughout the 1996–97

academic year, holding Q & A sessions and hearing presentations

from faculty leaders in Core instruction.

|

In spring 1997, a drafting committee prepared a curriculum proposal

that was modified by the Friday Group and then introduced to the

40-member College Council in June 1997. Early this year, the council

debated the proposal in six meetings, then approved the revised

curriculum by a 3-to-1 vote. At the same time, the council called

for another review of the curriculum no later than 2002.

Boyer compares the new cur-riculum to another “new” set of courses—the

New Plan of the 1930s, which required undergraduates to take 15

quarters of general education in their first two years in the College.

This was accomplished through five yearlong survey courses, representing

each of the four divisions and a course in writing. The second two

years were devoted to more specialized study.

The undergraduate curriculum has changed frequently over the intervening

decades. In what was known as the Hutchins College of the 1940s,

it focused almost exclusively on general education. President Hutchins’s

successor, Lawrence Kimpton, ushered in a two-plus-two structure,

calling for half of students’ education to be de-voted to general-education

courses, with the rest divided between a concentration and electives.

The general-education portion of the curriculum was not termed

the Common Core until 1966–67. While its name has stayed the same

for 30 years, its content has varied. At times, it consisted of

only prescribed courses and at other times of a combination of prescribed

courses and a “menu” of options. Often, the Core has taken many

students more than two years to complete.

Designed to allow students to complete their common studies in

the first two years and to spend the next two on advanced work in

concentrations and electives, the new Core will consist of six quarters

of natural and mathematical sciences, six quarters in the humanities

and civilizations, three quarters of social sciences, and—rather

than required coursework—demonstrated competency in a foreign language.

Students will divide the balance of their courses—a total of 42

are required for graduation—between concentrations and free electives.

The number of concentration courses will hold at current levels,

while the number of elective opportunities will increase.

“The new curriculum is the outgrowth of an exhaustive process,”

says Boyer. “The faculty are passionately committed to providing

the best possible liberal education for our students, which is why

they have spent three years thinking about the vital issues that

informed the construction of this new curriculum.

“The Chicago Plan—which is what I personally hope our new curriculum

will come to be called—introduces students to several broad domains

of knowledge while explicitly focusing on the intellectual habits

of inquiry, analysis, and writing.”

Boyer sees several advantages to the new curriculum, especially

that it continues to offer “a rigorous program of general education,”

but concentrates the Core classes in the first two years, helping

students to make the transition between high school and higher learning.

Currently, many students don’t finish the Core requirements until

the third or fourth year.

“[That] makes no pedagogical sense,” notes Bert Cohler, AB’61,

the William Rainey Harper professor in the College and the spokesperson

of the Committee of the College Council. “Juniors and seniors should

be doing advanced work. There are few other places in the country

where they have the opportunity to hunt for dino-saur bones one

week and visit a clinic for chronically mentally ill patients the

next.”

Boyer adds that the general-education courses will become more

interdisciplinary, integrating work in the humanities and social

sciences as well as in the biological and physical sciences. And

in another echo of the New Plan of the ’30s, “resources devoted

to the development of student writing will double,” Boyer points

out.

Students will also have more electives with which to explore on

an advanced level interests stimulated by their Core courses. “To

the extent that the new curriculum allows many students to move

more quickly to higher levels of learning, it should result in a

more challenging educational experience,” he says. “We believe that

allowing our students more opportunity to play to their considerable

strengths will strengthen the College.”

In addition, Boyer says, students will also be able to use some

of their elective courses for advanced foreign-language learning

and foreign-study opportunities, as well as advanced courses in

writing. For example, the College has be-gun a global-learning initiative

and a foreign-language-proficiency certificate program. The College

will also increase support for the Little Red Schoolhouse and add

advanced courses in creative and expository writing.

Boyer is enthusiastic about the new Chicago plan: “The dedication

of our faculty to designing and teaching imaginative general-education

courses and superior concentration programs lies at the very heart

of the University’s traditions, and such dedication will continue

to define the work of the College in the coming century.”—K.S.

|