|

||

|

Features ::

Lives of a Poet

Hayden Carruth, AM’47, has the trappings of a successful writer, including the National Book Award for Poetry. But his long road to literary laurels has had more than its share of agonizing detours.

Hayden

Carruth was 33 years old when doctors told him he would never again

live a normal life. He had served in the Second World War, earned a master’s

degree at Chicago, and gone on to edit Poetry magazine, one of

America’s most distinguished literary journals. In 1949 Carruth, AM’47,

took the bold step—bold for such a young and unknown editor—of

defending Ezra Pound, scorned for his pro-Fascist wartime broadcasts, when

Pound received the Bollingen Prize. He envisioned a long career as a poet,

critic, and editor.

Hayden

Carruth was 33 years old when doctors told him he would never again

live a normal life. He had served in the Second World War, earned a master’s

degree at Chicago, and gone on to edit Poetry magazine, one of

America’s most distinguished literary journals. In 1949 Carruth, AM’47,

took the bold step—bold for such a young and unknown editor—of

defending Ezra Pound, scorned for his pro-Fascist wartime broadcasts, when

Pound received the Bollingen Prize. He envisioned a long career as a poet,

critic, and editor.

But this promise seemed lost when he suffered an alcoholic breakdown in New York City and ended up at the White Plains branch of New York Hospital, formerly the Bloomingdale Asylum. In The Bloomingdale Papers, poems composed during his hospitalization, he wrote:

The diagnosis is

Anxiety psychoneurosis

(Chronic and acute)

Complicated by

Generalized phobic

Extensions and alcoholism.

Fifteen months in the “loony bin,” as he calls it, failed to cure him. His crackup was in part the result of phobias and anxieties that had haunted him all his life, complicated by the alcohol he drank to keep them at bay. After his release he spent most of the next decade in seclusion, too wracked with fear to venture out. He continued to write, but it was, he has said, “like squeezing old glue out of the tube.”

He never recovered completely, but he did manage to reenter the world. Drugs helped, as did the friendship of an understanding psychiatrist. So did music, work, the love of women, and two decades spent scraping a living in northern Vermont. There, far from the trodden paths of literary advancement, he began to regain his footing and find his voice. He did it by becoming “a yokel, a countryman, a guy who split wood and worked in a potato field”—and a poet of unusual range and power.

His first book of poems, The crow and the heart, came out in 1959, five years after he left the hospital. Some 30 books followed, mostly poetry but also a novel, an anthology of American poetry, a collection of autobiographical essays, and a volume of letters to the poet Jane Kenyon published last September. He has published several collections of reviews—work taken to pay the bills but that has earned him a reputation as a first-rate critic. And he has written a book of essays on jazz and the blues, lifelong fascinations.

His poems explore the landscape of suffering and loss and are finely pitched to what Keats called the “still sad music of humanity.” Carruth is also a poet of the erotic, alert to and grateful for the possibilities of joy. His poems are technically accomplished—and deeply personal. He draws upon philosophy, history, and literature while writing about everyday matters, from the hard lives of Vermont hill farmers to his struggles with mental illness. Gritty and unsentimental, his poems are disarmingly forthright. Wendell Berry, the Kentucky farmer and poet, has said, “In his poems mind and heart speak as one, and his work has, in rare degree, the quality of trustworthiness.”

Yet

for many years Carruth earned little recognition. Vermont named him

poet laureate only after he had left for upstate New York. But at 83 he

has accrued a growing band of admirers and earned honors that long eluded

him, including the National Book Critics Circle Award and the National Book

Award. Writing in the Nation in 1991, editor Ted Solotaroff, AM’56,

praised him as “a people’s poet, readily understood, a tribune

of our common humanity, welfare and plight.” Carruth, he said, “has

worked as much in the American grain as any figure of his generation.”

Yet

for many years Carruth earned little recognition. Vermont named him

poet laureate only after he had left for upstate New York. But at 83 he

has accrued a growing band of admirers and earned honors that long eluded

him, including the National Book Critics Circle Award and the National Book

Award. Writing in the Nation in 1991, editor Ted Solotaroff, AM’56,

praised him as “a people’s poet, readily understood, a tribune

of our common humanity, welfare and plight.” Carruth, he said, “has

worked as much in the American grain as any figure of his generation.”

Carruth today lives in the hilly limestone country between Utica and Syracuse. He and his fourth wife, Joe-Anne McLaughlin-Carruth, have a small red house perched on a hillside just outside the town of Munnsville, with a wide view of Stockbridge Valley. He bought the house on impulse in 1988 while on the faculty at Syracuse University, where he taught for a decade after leaving Vermont. A birdfeeder stands crookedly out front, and daisies and hawkweed flower in a nearby meadow. Traffic whooshes past, too close, on New York State Highway 46.

On a gray, drizzly day last August, he rises late and eats breakfast at 1:30 p.m. This is typical for Carruth, who even as a child suffered from insomnia. With a raspy but cheerful “Come in! Come in!” he walks to the door in slippers, baggy shorts, and a sleeveless undershirt. His green eyes are small and watery, his skin sallow from too much time indoors. He trails a line of clear plastic tubing that delivers oxygen to his nostrils from a pump humming in his living room—the consequence of emphysema from a lifetime of smoking. With untrimmed white beard and flowing gray hair, he has an ancient, wild look.

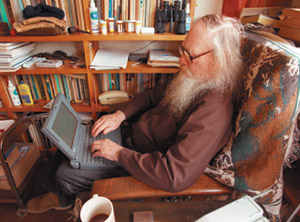

Since open-heart surgery three years ago Carruth has moved more slowly. He sometimes shuffles up the road, pushing his oxygen tank in front of him, but even this modest exercise is difficult. He hardly goes anywhere except to accompany his wife to the store, or to visit her relatives in New Jersey. He gives occasional readings, as he did last fall in Vermont, but spends most of his time at home, watching birds at the feeder, listening to the radio or watching TV, or slouched in a soft chair in the middle of a cluttered study, tapping out letters or other work on his laptop.

Carruth’s wife, also a poet, hovers near him, a slender woman with thick auburn hair. Despite a 30-year age difference, the two are close; they share their solitude in a town where both feel like exiles. Carruth’s poems pay frequent homage to his wife and her predecessors, sometimes in ways too personal for her taste. “He just has no sense of privacy,” she complains. “None! He’ll tell people anything. And he thinks that’s the way you should be in the world.” Carruth grins. Bluntness and candor are old habits.

Women have been an indispensable ingredient in his life. Whatever pain his relationships have caused—and there has been plenty on both sides—women have led him again and again out of the prison of his anxieties and back into the human community. He has married them, left them and been left, longed for them, depended on them—and written about them, as in “Wife Poem”:

…His last

cigarette, his final gulp of chardonnay,

and he presses against her warm glow,

thinking of how he swam as a boy

of twelve in the warm pond beyond

the elms and hickories at the meadow’s

edge. He turned like a sleepy carp among

the water lilies, under the dragonflies

and hot clouds of the old days of summer.

Rejecting God and religion and what he sometimes dismisses as “Christian bullshit,” Carruth seeks no more transcendence than what human love affords. “The women in my life got me through, and sex with them got me through,” he says. “I think it’s more fun than anything else in the world, and more meaningful than anything else. Now I’m old and decrepit and I can say these things.”

Carruth celebrates communion of all sorts. As singular and outspoken as he can be, he thinks the ideal of American individualism is dangerous and inherently violent. He knows too well the costs of solitude, and his poems display a respect for ordinary people. He has a soft spot for animals. Smudgie—or Miss Smudge, as he calls the cat more formally—was a thin, disease-ridden stray when he took her in a decade ago. “She’s nothing but bones and fur,” he says, picking her up and stroking her lank body. “But she’s a nice little cat. And she likes me and I like her, so we take care of each other.”

Carruth admits to being “a pessimist, skeptic, and grump.” He has written an entire poem against the assumption, perpetuated by the movies, that when someone hangs up the phone the person on the other end hears a dial tone. He has a sly, often self-deprecatory sense of humor. In “While Reading Bashõ” he addresses the Japanese poet:

Had you air, Bashõ?

I mean enough to climb those

mountains? Or did you

stop every ten steps,

leaning on your staff and gasping

like a fish ashore?

Heavy drinking has at times made him difficult company. And yet he has the gift of friendship. He has been especially helpful to the young poets he has known. The Vermont poet David Budbill describes Carruth as “a temperamental, explosive, cantankerous, wonderful, generous, kind person.”

On the day after his 83rd birthday, Carruth is in excellent spirits. His wife brews coffee and serves leftover birthday cake, which he eats with relish. Sitting at the kitchen table, he talks for hours—by turns gracious, opinionated, and funny. “I’m pumped!” he says late in the day.

Carruth, whose grandfather wrote speeches for Eugene Debs, calls himself an “old-line anarchist” and a “rural communist with a small c.” On this day he grumbles about President Bush. In 1998 he declined an invitation to the Clinton White House for a celebration of American poetry, explaining in a letter that “it would seem the greatest hypocrisy for an honest American poet to be present on such an occasion at the seat of the power which has not only neglected but abused the interests of poets and their readers continually, to say nothing of many other administratively dispensable segments of the population.” He has long resisted the notion that politics—or anything else—doesn’t belong in poetry. His poems are democratic in the broadest sense, siding with the weak against the powerful, oppressed against oppressor. His sympathies extend even to despised creatures like rats and car salesmen. “I’ve always felt sorry for the rats,” he says.

A cry of protest rings through his work, an echo of what the New Yorker called his “well-tuned orneriness.” He has written antiwar poems protesting Bosnia, Vietnam, Korea, Waterloo, and Troy. In “Emergency Haying” he uses an anecdote about helping a neighbor bale hay to condemn suffering on a much wider scale:

…. My hands

are sore, they flinch when I light my pipe.

I think of those who have done slave labor,

less able and less well prepared than I.

Rose Marie in the rye fields of Saxony,

her father in the camps of Moldavia

and the Crimea, all clerks and housekeepers

herded to the gaunt fields of torture….

… And I stand up high

on the wagon tongue in my whole bones to say

woe to you, watch out

you sons of bitches who would drive men and women

to the fields where they can only die.

For Carruth the world is suffused with sadness. In a 2003 interview he recalled as a child “looking at the stars in the summertime…and feeling a tremendous sorrow from simply knowing that they are not permanent.” But his awareness of impermanence does not keep him from finding opportunities to celebrate and affirm. Music, especially jazz and the blues, has given him many. In Chicago he taught himself to play the clarinet and frequented jazz clubs like the Bee Hive on 55th Street. After his hospitalization he played the clarinet for hours each day, sometimes accompanying Music-Minus-One recordings. His essays have celebrated jazz musicians and explored links between jazz and literature. Calling jazz “an eloquent articulation of every serious artistic, social, cultural, and philosophical happening in my lifetime,” he suggests in the poem “Freedom and Discipline” that, at some level, poetry and jazz are one:

Freedom and discipline concur

only in ecstasy, all else

is shoveling out the muck.

Give me my old hot horn.

Carruth

grew up in Woodbury, a small country town in western Connecticut.

His father and grandfather were writers and editors, and he assumed he would

follow in “the family racket.” He studied journalism at the

University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, where he worked for the student

newspaper and met his first wife, Sara Hudson, AM’47, PhD’58.

“He was interesting and full of life and ideas,” recalls Hudson,

professor emerita of English at Auburn University. “We were all gung-ho

New Dealers. We had a lot in common that way.” They married in 1943

on graduation day and enlisted in the Army, Carruth in the Army Air Corps

(serving in Italy) and Hudson as a WAC. After the war they took advantage

of the G.I. bill to enroll at Chicago.

Carruth

grew up in Woodbury, a small country town in western Connecticut.

His father and grandfather were writers and editors, and he assumed he would

follow in “the family racket.” He studied journalism at the

University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, where he worked for the student

newspaper and met his first wife, Sara Hudson, AM’47, PhD’58.

“He was interesting and full of life and ideas,” recalls Hudson,

professor emerita of English at Auburn University. “We were all gung-ho

New Dealers. We had a lot in common that way.” They married in 1943

on graduation day and enlisted in the Army, Carruth in the Army Air Corps

(serving in Italy) and Hudson as a WAC. After the war they took advantage

of the G.I. bill to enroll at Chicago.

“We just thought it would be more fun to go to school than to get a job,” Carruth says. It turned out to be an intellectual awakening. His earlier literary education had been fusty and antiquarian. At Chicago he took courses in 20th-century literature, bought literary magazines at the 57th Street bookstores, and made friends with other aspiring writers, such as Henry Rago, a poet and teacher who became one of his closest friends. Carruth had been writing poems since childhood; now he began to write more seriously and with a heightened understanding of poetry’s possibilities.

“Coming to Chicago, at that time and in that atmosphere, which you can’t altogether recover...was a very liberating experience,” he says. “You can’t read Ezra Pound and T. S. Eliot and people like that without getting the idea that poetry is really important, and that poetic language is pure and has a certain element of social significance to it, and social influence. I bought that line completely.”

Realizing that he was not cut out for academe, he abandoned his studies and went to work at Poetry magazine, which had already begun to publish his poems. Soon afterward, in spring 1950, he was promoted to editor. Poetry had a distinguished record of discovering and championing the best new American poets, and its offices were still a crossroads of literary activity in Chicago. Yet Carruth felt the magazine had grown staid. As he would write to his successor, Karl Shapiro, “Poetry was a pussyfooting magazine for so long it damn near collapsed, & what it needs is a little life.”

He tried to give it that life. He expanded its prose section of essays, reviews, and editorials, some of which he wrote himself. He campaigned in the magazine in support of Ezra Pound and the committee that had awarded him the Bollingen Prize, praising Pound as “the poet whom nearly all of us would have to nominate as the single living person who has done the most to explore and develop the technical capacities of poetry in English.” On a broader, more philosophical level he defended modern poetry and decried “the enemies of poetry, who are also the enemies of life.”

Carruth’s Chicago years shaped his sense of vocation, but they also brought growing difficulties. His anxieties became pronounced. He suffered from extreme stagefright and once fled a class he was teaching at a Gary, Indiana, college. Walking down the street was equally harrowing: several times he collapsed on the sidewalk from the strain. He began to see a psychoanalyst, but it didn’t seem to help. “He was getting worse,” Hudson says. “He said he’d rather be blind than have what he was afflicted with.”

Carruth drank a lot—everyone seemed to. “We had great parties, and probably too much drinking,” says Hudson. His domestic life grew increasingly tumultuous. When upset, he’d jump in his car and drive off, sometimes disappearing for days. “Hayden is very headstrong and is determined to do, often against his best interest, what he feels he has to do,” Hudson says. “I can only describe it as compulsive. And it was self-destructive.”

His job at Poetry also soured. He clashed with the magazine’s trustees, who felt uncomfortable with his forays into literary politics. For his part, Carruth chafed at restrictions: the trustees had insisted that other editors approve any poems the young editor published. Carruth’s behavior also offended. In the middle of the night, Hudson recalls, Carruth called up trustee Marion Strobel and, with his wife imploring him not to, told Strobel he was quitting. In January 1951, less than a year after he became editor, Poetry’s trustees replaced him.

Losing his job was a blow, but a worse one followed. Months after the birth of their daughter Martha (a painter who died in 1997), Hudson left him, returning to Alabama with their child. The split would haunt him for years. It was, he once reflected, the “principal and determinative fact of my life.”

Carruth found a new job at the University of Chicago Press, where he met Eleanor Ray. When Ray moved to New York he followed, and they both found publishing work. Their marriage in 1952 was short-lived. Carruth’s mental state was fragile, and in summer 1953 he fell apart. His psychoanalyst found him drunk in his apartment and urged him to seek hospitalization. “I had one of my abandonment crises,” Carruth explains. “That’s a phobic part of my psychopathology. Nobody knows what started it exactly. But I can’t stand to be alone. I go completely off the rails.”

So Carruth entered Bloomingdale. At first his doctors urged him to write poems as therapy. He used a portable typewriter, sitting before the window of his small cell. Two decades later, in 1975, the University of Georgia Press published The Bloomingdale Papers, which gives an account of the forces that led to his breakdown:

I don’t mean to say

There weren’t good times.

The bad predominated.

Booze helped immensely.

Work also, but not,

Unfortunately, writing.

Friends and parties and lovers

Lent ease to my unease

Sparingly. The doctors kept

The anxious pot aboil.

So passed the years.

The writing therapy failed to cure him. A few months later, he was transferred to a ward for chronic cases and underwent a series of electroshock treatments. For the rest of his stay he wrote no more poetry. Instead he watched the McCarthy hearings on television and played, by his count, 1,500 games of solitaire. But he kept trying to get his poems published. On June 26, 1954, he sent a batch of poems to Shapiro, Poetry’s new editor, with an apologetic note: “I am very sorry to submit to you such unprintable manuscripts, and without any return postage, but that is the best I can do in this place. I hope you don’t mind. Please exercise your judgment severely on these.”

When he left the hospital he was in worse shape, he says, than when he entered it. He spent the next five years living in an attic room in his parents’ house in Pleasantville, not far from White Plains. In 1999, in a short essay in The Sewanee Review, he described his state of mind:

Agoraphobia is when a stranger enters the house and you go to the attic and lie down with your face pressed into the darkest corner, under the slanting slats of the roof. It’s the scream lurking in your gorge, so ready to burst that the least noise above a cat’s purr makes you tremble: when the marching band from the high school practices in the street outside you sit in the back of the closet, when the March wind lashes the treetops at night you crawl behind the sofa. Agoraphobia is when every night at 2:00 a.m. for five years—that’s 1,825 nights—you go out loaded with Thorazine to walk in the street beneath the dark, blank windows of the houses on either side, and you never get more than a hundred yards from your door. ... Agoraphobia is when you breathe and eat the dust of oblivion.

Carruth was not especially close to his family. Although his younger brother Gorton attended the U of C when he did, their paths seldom crossed. “He ran his life and I ran mine,” says Gorton, PhB’48, now living in Briarcliff Manor, New York. It didn’t help that Carruth wrote unflattering accounts of family dynamics. Of his lifelong smoking habit, which began when he picked up cigarette butts as a nine-year-old, he wrote that it was one way to defy “the whole mind-set of Carruthian secular and neurotic puritanism” and “the fear of talking about it, of talking about anything that might be charged with negative feeling”:

Cigarette smoking was a way to cross the immense barrier between the Carruths and the rest of the world, which I wanted to do more than anything. I wanted to be ‘out there’ with the others, away from solitude and fear. I never made it and never will. Precisely how this dynamic knot of attraction and repulsion evolved over the years and became an ineradicable component of my being, is unknown to me. I doubt anyone could figure it out except in gross, uninteresting terms. But I know it is there, close to the heart of my psychopathological life, creative and destructive, a strength, a weakness, a function of the basic energy that has always driven me.

Carruth tried with difficulty to keep up with friends. “You do have your beautiful lake, though, which I think of often with great longing,” he wrote to Henry Rago, who had become editor of Poetry. “Someday I hope to see it again.” In 1958 he sent Rago some poems but suffered doubt, saying, “I am timorous about many of these things because I know they are not in the fashionable mode and, aside from my poor talents, may seem simpleminded. I work as I must, however.” Turned down for a Ford Foundation grant, he despaired, “I begin to perceive that I am pretty much a has-been in this literary business.”

His most pressing concern was how to make a living. An office job like those he’d held in Chicago and New York was out of the question. His publishing contacts eventually helped him pick up contract work, reviewing books, writing blurbs, ghostwriting, and editing encyclopedias. He spent four years compiling his anthology, The Voice That is Great Within Us: American Poetry in the Twentieth Century. Once, desperate for work, he typed manuscripts for $1 per page. This “hackwork,” as he called it, occupied his time and energy for the next 25 years. He resented it but took it seriously. “I did a good job,” he says. “I know grammar up and down and backwards. I had a pretty good vocabulary. I can fix up people’s manuscripts—I spent my life doing it, poetry and prose. And I’ve done it for money when I could get it.”

During his isolation Carruth continued his education. “On the weekends I read Aristotle, who strains my inexperienced brain fearfully,” he wrote Rago in 1959. “My aim is to live to be 90 and complete my education at 85. This will give me a five-year vacation.” Of the hundreds of books he read, Camus struck him most forcefully. As much as the writer’s existentialist convictions, he admired his commitment to truth, and resolved to adopt a similar stance: “I had to say to myself when I was in my 30s, with Camus in mind, that I’m going to write what I know is honest and true about myself with my own talent,” he says. “I started out writing formal poetry, not only formal in language but formal in attitude, trying to be the big Eliot-type person. And it wasn’t for me at all. I realized if I was going to get anywhere at all, either in literature or in life, I had to change, and I had to become open, totally.”

After five years in his parents’ attic Carruth improved enough to move to Norfolk, Connecticut, where he lived in a cottage that belonged to James Laughlin of New Directions books—Ezra Pound’s publisher—whom he’d met while at Poetry. He did editorial work for Laughlin, and he met Rose Marie Dorn, a young refugee from Eastern Europe. In 1961, at age 40, he married for the third time. The couple had a son, David, and when they went looking for a home they concluded that the only place they could afford to buy was in northern Vermont. They found a house with 14 acres and a creek outside the town of Johnson, near the spine of the Green Mountains, 25 miles from Canada.

Carruth worried that the residents would distrust him because he was college

educated and wrote poetry. But when he proved he could fix machinery and

cut wood, they accepted him. “I had a lot of friends, many country

people, in the town of Johnson and surrounding towns. I worked on their

farms, and they helped me on my place.”

He helped his nearest neighbor, a dairy farmer named Marshall Washer, do

chores in exchange for milk. He raised a garden, kept ducks and chickens,

and sold eggs. It took him a month each year to cut enough wood to heat

his house during the long winter. As he makes clear in “Concerning

Necessity,” this was no rural idyll:

ho we say drive the wedge

heave the axe run the hand shovel

dig the potato patch

dig ashes dig gravel

tickle the dyspeptic chain saw

make him snarl once more

while the henhouse needs cleaning

the fruitless corn to be cut

and the house is falling to pieces

the car coming apart

the boy sitting and complaining

about something everything anything

Earning a living meant doing manual labor during the day and hackwork in the evening. Only after midnight could he turn to poetry. In his workroom, a one-cow barn he had wired and fitted with a woodstove, he wrote until five or six in the morning before going out to shovel snow or to split wood.

“It was a hard life, but it was not impossible,” he says. And it did him good. Everything about his life in Vermont—the work, the land, the seasons, the people, his family—seemed to carry him toward “a gradual triumph over the internal snarls and screw-ups that had crippled me from childhood on.” Budbill says that Carruth couldn’t ride a bus or read his poems before an audience but functioned well enough with the individuals and small groups he might run into on trips to town. “He’d stand around and jaw with whoever was there, for hours,” Budbill says. “In those kinds of contexts, with ordinary people, in the feed store, restaurants, wherever, he was as gregarious as any human being could be.”

Vermont also transformed Carruth’s poetry. At times his work made writing poetry impossible, and he almost forgot he was a poet. Yet his poetry became more vital, liberated. “I could write poetry about things I really knew something about,” he says. “I could write about simple things in simple language and I wanted to do that. ... I didn’t want to be Robert Frost exactly. I mean I definitely didn’t want to be Robert Frost. I didn’t like much of his poetry and many of his attitudes. But I did want to be a country poet who was appreciated and read as widely as possible.”

His country poems are among his most popular and highly praised. Poems like “Marshall Washer” describe with intimacy and straightforward affection the land, its inhabitants, and a way of life that was dying even as he wrote about it.

They are cowshit farmers, these New Englanders

who built our red barns so admired as emblems,

in photograph, in paint, of America’s imagined

past (backward utopians that we’ve become).

But let me tell how it is inside those barns.

Warm. Even in dead of winter, even in the

dark night solid with thirty below, thanks

to huge bodies breathing heat and grain sacks

stuffed under doors and in broken windows, warm,

and heaped with reeking, steaming manure, running

with urine that reeks even more, the wooden channels

and flagged aisles saturated with a century’s

excreta.

Carruth has a sharp eye for nature and humanity. Until recently, his wife says, he carefully recorded the daily weather, including temperature, rainfall, and barometric pressure. His Vermont poems adopt the voice and point of view of ordinary people, like this old hill farmer in the long poem “The Sleeping Beauty”:

...I mind

When them old hooters had plenty eating material

Round these parts, and other folk too. Course

That were times gone. You could prevail

With but fourteen head of cows

Then, if you had the makings.

Makings?

What I call

Makings of a man. And that means straight out all

The time, with children on the way,

An orchard, guarding, a fair stand of hay,

Pigs, chickens, you know—what we meant by farming

In those days. It’s all changed now.

In Vermont Carruth was not cut off entirely from literary society. In summer he had visits from such admirers as Mark Van Doren, Denise Levertov, and Adrienne Rich. The 1960s back-to-the-land movement also brought younger poets to Vermont. He encouraged their writing, though their friendships were not primarily literary, says Budbill. “It was mostly based on country life, exchanging recipes, helping each other split wood, smoke a pig. We talked a lot more in those days about pickups and quality of the wood than about poetry and iambic pentameter.”

By 1979 Carruth was working 80 to 90 hours a week and still earning too little to support his family. He tried unsuccessfully to find full-time work at a Vermont college or university, and when Syracuse University offered him a professorship in its graduate program in creative writing, he left Vermont—and his wife—for suburban Syracuse and the more conventional academic life of a contemporary poet. It took him time to get used to teaching. His anxieties persisted; too afraid to cross the university quadrangle, he skirted around the edges. In 1985 he returned to Vermont, but a year later was back in Syracuse. In 1988 a breakup with a girlfriend led him to attempt suicide.

Still, Syracuse led to a new stage in his development as a poet. Living on the city’s outskirts he began writing poems inspired by people he encountered along the commercial strips, poems gathered into Asphalt Georgics (New Directions, 1985). And a series of honors arrived. It was the professorship, Budbill suspects, that finally admitted Carruth “into the circle of acceptance” and led to his Collected Shorter Poems: 1946–1991 (Copper Canyon Press, 1992) earning the 1992 National Book Critics Circle Award. Four years later Scrambled Eggs & Whiskey: Poems 1991–1995 (Copper Canyon Press, 1996) won the National Book Award.

The awards have made him feel no less an outsider. He remains bitter about what he considers his marginalization by the literary establishment. Yet his admirers have not stinted their praise. As long ago as 1986 M. L. Rosenthal declared in the New York Times that Carruth “has now become our elegist par excellence.” Joseph Parisi, AM’67, PhD’73, another of his Poetry successors as editor, admires Carruth’s perseverance. “It’s a remarkable story of endurance, of tremendous power of will,” Parisi says. “I think it’s a heroic life myself. Hayden is a genuine poet who has never been one to play the game, which is what so many writers do now. Instead of being a smooth, glad-handing, conference-going kind of guy, he kept his energies focused on what was important, which was his work.” Writes Pulitzer-winning poet Galway Kinnell, “More than in the case of any other poet, Carruth responds to Whitman’s words: ‘I was the man, I suffer’d, I was there.’”

For Carruth struggle has been the stuff of life and poetry. “If you’ve got any courage and any sense of responsibility, you’ll do what you have to do,” he observes. “I don’t give myself any extraordinary credit for that. But the difficulties were there and the difficulties made my poetry better. I’m convinced of that.”

The final adversary, old age, is, and has been, upon him. He has written about that too, in poems like “Song: Now that She is Here”:

Old age is failure. Natural

Exhaustion, mind and body letting go,

Words misremembered, ideas frayed like old silk.

Carruth still writes poems, but not often, and none that satisfy him. He has abandoned his most ambitious project, a four-part epic called American Flats, which was to have begun with the conquest of Mexico. He’s too old, he says, tapping his forehead. More and more thoughts of death crowd his mind. Most of his old friends are gone, including his Vermont neighbor, the farmer Marshall Washer, who died in 2003.

What is left? In an autobiographical essay, Carruth compares writing a poem to sexual climax. “In the ecstasy of composition,” he says, the poet “is most himself, yet…at that very moment is also aware of his communion with many others, or with the great Other at the center of humanity.” When the poem is finished, he says, the knowledge of communion doesn’t vanish. It remains:

So it is for the old man in his cave of darkness, regretting his arthritis and impotence and failing imagination. The knowledge of communion is still there.

Richard Mertens is a freelance writer and a doctoral student in the

Committee on Social Thought.