Lecture

Notes

Lecture

Notes

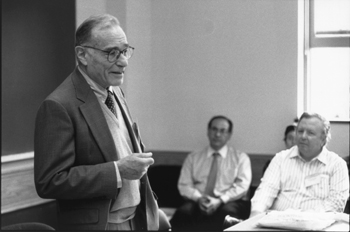

Seeing

beyond the eyes

How

do humans see? "The commonsense view is that we have eyes,

and so we see," says Sidney Schulman, the Ellen C. Manning

professor emeritus in the Biological Sciences Division. "But

the truth is we see with more than our eyes."

This

fall students in Schulman's course, Neurology and Kant's Theory

of Knowledge, are learning to see with philosophical as well

as scientific eyes, using one perspective to illuminate the

other.

"Immanuel

Kant didn't talk about the nervous system-he didn't even know

it existed," says Schulman, SB'44, MD'46. "But reading

his works, I began to see connections. The question for both

is: how is this piece of organic matter called the human being

able to know the space and matter around him?"

Schulman,

who has taught at the University since 1950 and has taught this

course since 1980, began closely studying the 18th-century philosopher

after finding arguments similar to Kant's theories in the works

of Heinrich Klüver, a German neurologist.

"Kant's

theory of perception is strikingly in accord with present-day

scientific thinking," says Schulman. "Neither sensation

alone nor thinking alone can account for the human experience

of the world around us. Both are essential and must work in

partnership."

The

approach is unusual, Schulman admits. "Many scientists

scorn and make fun of philosophers, but science started with

philosophy. It's a curiosity about the world that drives them

both."

The

class is a small discussion group of five students, mostly biology

concentrators. They read the first half of Kant's Critique

of Pure Reason, scientific papers on neurology, and Donald

Hebb's Organization of Behavior. Requirements include

a midterm, a final exam, and the occasional pop quiz.

-W.W.

![]()

Lecture

Notes

Lecture

Notes