Beyond

the bomb

>> The

physicists who gathered at Chicago to commemorate the centenary

of Enrico Fermi's birth celebrated not the father of the atomic

age, but a man they recall as a remarkable colleague and teacher.

Enrico

Fermi would have been 100 years old this year, and although he

died in 1954, well short of that mark, there are still enough

of his former colleagues and students around to celebrate. On

September 29, the centenary of Fermi's birth in Rome, dozens of

them gathered at the University of Chicago to swap anecdotes,

relive old experiments, and remember a man who did as much as

anyone to unlock the secrets-and the power-of the atom.

September's

gathering was not the first time Fermi had been formally remembered

at the University. Fermi, who came to the quads in 1942, three

years after he received a Nobel Prize for his research into subatomic

particles, joined the faculty in 1946 and spent most of the rest

of his life at Chicago, working on theories of cosmic ray acceleration

and smashing atoms with the university's new cyclotron, then the

most powerful particle accelerator in existence.

It

was for another experiment, of course, that Fermi earned his reputation

as father of the atomic age. In 1942 in a squash court under the

stands at Stagg Field, he and a group of coworkers secretly assembled

a pile of graphite and uranium that yielded the first controlled,

self-sustaining nuclear reaction. The "atomic pile,"

as they called it, was a crude atomic reactor that opened the

way for the peaceful use of atomic power-but also, and more immediately,

for the bombs that fell on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945.

The

work at Stagg Field has been commemorated regularly, most recently

on its 50th anniversary in 1992. This year the focus shifted away

from Fermi's contribution to the Manhattan Project to his legacy

as a colleague and teacher.

The

chain reaction "has been celebrated here so many times,"

explained James W. Cronin, SM'53, PhD'55, University professor

emeritus in physics and astronomy & astrophysics and the reunion's

host. "What has not been celebrated here is Fermi's work

after the war. It was basic science. It wasn't bombs." Cronin,

also a Nobel laureate, learned some of his physics as a student

in Fermi's classrooms. "Fermi from 1946 to 1954 was really

trying to understand nature in all its aspects," he said.

"That's what I wanted to bring out. Also, it's about the

last chance to bring back people who can remember that time."

Indeed

many of the physicists who crowded the lobby of Ida Noyes Hall

on a sunlit September morning were gray and frail, although it

became clear as the day wore on that they were undiminished in

their enthusiasm for Fermi. About 70 physicists who knew Fermi

attended the reunion. Their number included four Nobel laureates,

reminders that Fermi's years at Chicago marked the University's

golden age of physics. Altogether the event drew as many as 300

people, including physicists and aspiring physicists too young

to have known Fermi but well aware of their debt to him.

"Fermi's

footprints are all over everything I do," said Henry Frisch,

a professor of physics at Chicago. "I think of him a lot.

The particles I deal with all the time, he would have been delighted

to see-and not terribly surprised."

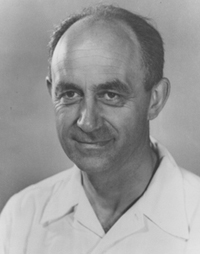

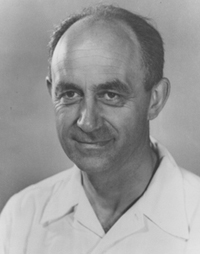

Fermi

was honored first not by his old colleagues and students but by

the U.S. Postal Service, which opened the celebration by unveiling

a 34-cent stamp bearing his image. The stamp shows Fermi standing

at a blackboard in a three-piece wool suit, his left hand in his

pocket, his right holding a piece of chalk, his broad face wearing

a genial smile. (Although it wasn't mentioned from the podium,

the chalked notations contain an error, and Cronin says Fermi

may have been asked to put some scientific-looking stuff on the

board as background for the photo session: "He might have

been pulling our leg.") Proclamations were read: the mayor

and the governor had declared it Enrico Fermi Day. From then until

well into the evening, breaking only for meals and refreshments,

Fermi's colleagues and students reminisced about their absent

friend.

Predictably,

they devoted much of their conversation to sheer physics. Frank

Wilczek, AB'70, a professor at MIT and a self-described "great-grandson"

of Fermi, spoke on "Fermi and the Elucidation of Matter,"

and from then on the air was thick with talk of pions and neutrons,

beta radiation and cosmic rays, angular dependence and phase shift

analysis. The physicists bent forward to hear accounts of Fermi

bouncing neutrons off mirrors and scattering pions with his cyclotron,

or any of the other experiments he carried out a half century

ago. "He loved those experiments," said Albert Wattenberg,

PhD'47, who as a student and researcher helped Fermi with many

of them.

Nothing

excited Fermi so much as a new problem to solve. It hardly mattered

what the problem was. Wattenberg recalled one afternoon when Fermi

sat with a group of students at a long table in Hutchinson Commons.

"He looks up at the dirty windows and asks, 'Well, how thick

will dirt get before it falls off?' He made us feel we could really

calculate anything. He, of course, could."

Fermi

shone brightest at Thursday afternoon seminars in Room 480 of

the Institute for Nuclear Studies. That was when he and his colleagues

gathered to discuss whatever happened to be on their minds. Faced

with a problem that stumped other physicists, Fermi often would

turn to the blackboard, pick up a piece of chalk, and solve the

problem with ease. Roger W. Hildebrand, today the Samuel K. Allison

distinguished service professor emeritus in physics and astronomy

& astrophysics, recalled the day when a colleague wanted to

know "if the age of water at the bottom of the ocean could

be explained by the churning of surface waves. Fermi said, 'Let's

see if we can work it out.' And he did. He did it using characteristics

of monster ocean waves that he had learned on a transatlantic

voyage. The oceanographers at La Jolla had worked on it for three

months. Fermi worked it out on the board in 15 minutes."

Part

of Fermi's gift as a scientist, as well as his effectiveness as

a teacher and his appeal as a human being, lay in his simplicity.

"He didn't care for fancy solutions," said Jack Steinberger,

SB'42, PhD'49, a former student now with CERN. He would explain

a difficult problem so clearly that he made the answer seem obvious.

"That was the way it was with Fermi," Hildebrand agreed.

"If something crossed your mind that you had never thought

of before, you thought it was your own idea."

Fermi

was brilliant; he was also modest, hardworking, and generous with

his students. "There were some gifted students, and some

of us who were less gifted," said Nobel laureate Steinberger.

"He was equally kind to us all."

Much

of the Fermi lore exchanged had little to do with physics or the

classroom. Colleagues recalled his proud athleticism, whether

swimming in Lake Michigan off Promontory Point, careering undeterred

down a half-snow, half-grass ski slope outside Chicago, or gleefully

outpacing younger hikers in the mountains near Los Alamos. Murray

Gell-Mann remembered how, at the Quadrangle Club one afternoon,

Fermi discoursed on how he might still, in theory at least, become

Pope. Fermi was fascinated by Li'l Abner, Gell-Mann said.

He read the comic strip faithfully in the hope that it would improve

his knowledge of American English. Uri Haber-Schaim, PhD'51, showed

a snapshot of Fermi working the handles of a foosball game. "He

thought statistically," Haber-Schaim explained. "He

used to whirl the thing like mad to increase the probability that

the ball would be hit. It didn't work." Richard L. Garwin,

SM'48, PhD'49, who worked under Fermi at Chicago and Los Alamos,

recalled Fermi's remark after an encounter with colleague and

sometimes rival Edward Teller (father of the hydrogen bomb): "That's

the one monomaniac I know with more than one mania." Garwin's

audience chuckled.

The

day was filled with such moments: nostalgic, affectionate, reflective.

"There's a fading away, although a hell of a lot of stuff

has been remembered," said Wattenberg, at 83 one of the oldest

of Fermi's former colleagues in attendance. "It's a wonderful

thing to reminisce about." Wattenberg had a lot to remember

himself; he began working with Fermi at Columbia University in

1939 and later followed him to Chicago. "I was very fortunate.

When I was a young college student, I thought my goal in life

was to help a Nobel Prize winner do experiments. I feel very good

about what's happened."

Although

the purpose of the reunion was to remember the physicist as a

teacher and colleague, the larger events of Fermi's day cast their

shadow, just as they had cast their shadow over Fermi's life.

His career corresponded to the rise of fascism, World War II,

and the early years of the Cold War, and like many physicists,

he played an important part in public affairs. "All these

men and women were caught up in a historical period of great difficulty,"

said Nina Byers, SM'53, PhD'56, a physicist at UCLA.

Byers

recalled the debate, in which Fermi played a central role, over

whether to use the atomic bomb against Japanese civilians in 1945.

Some physicists, including Leo Szilard and other members of the

University of Chicago faculty, argued that the bomb should be

exploded over an uninhabited area as a demonstration. But Fermi,

who was associate director of the Manhattan Project, agreed with

Robert Oppenheimer: "We can propose no technical demonstration

likely to end the war," they wrote in a report.

Darragh

Nagle, a colleague of Fermi's for many years, recalled Fermi's

chain reaction experiment by showing a photo of Stagg Field. "I

always thought of the architecture as Gothic," he said. "The

malevolent monster, of course, that was the pile. And instead

of chains to subdue the monster, there were control rods."

But

as Fermi knew, the creator could not long control his creation.

After dinner, Jim Cronin concluded the day's events on a sober

note by reading from a speech that Fermi wrote in 1954, near the

end of his life. In it, Fermi expresses a faith that the technological

and industrial applications of scientific discoveries can "revolutionize"

our lives. "It seems to me improbable that this effort to

get at the structure of matter should be an exception to the rule,"

he says. "What is less certain, and what we fervently hope,

is that man will soon grow sufficiently adult to make good use

of the power he acquires over nature."

For

the most part, Fermi's 100th birthday was not a day to ponder

such difficult questions. It was a day for the remnant of a disappearing

generation to remind one another, maybe for the last time, what

made Enrico Fermi so special. They described a man who loved science

and felt an insatiable desire to understand the world around him;

who was brilliant and accomplished but also modest and generous.

"He was truly a great man," said Jerome L. Friedman,

AB'50, SM'53, PhD'56, one of Fermi's students and a Nobel laureate.

"Nearly a half century later, I still look back on him as

a great physicist and a remarkable human being."

But

what stood out as memorably as the man they tried to describe

was the depth of their affection for him. Fermi was respected

and admired, but he was also loved. "Enrico Fermi was the

most important person in my life," Richard Garwin said bluntly.

"I was more affected by his death than by my father's."

One

of the day's most emotional moments came when Murray Gell-Mann

described the last time he saw Fermi, as Fermi lay dying of stomach

cancer at Billings Hospital. "When we got to the bedside,

Enrico kept telling us not to be downcast," Gell-Mann said.

"It is not so bad, he said." Gell-Mann's eyes brimmed

for a moment with tears as he recalled Fermi's parting words.

"'Now,' he said, 'it is up to you.'" Nearly a half century

later, it was still hard to see Enrico Fermi go.

Richard

Mertens, a student in the Committee on Social Thought, is a freelance

writer and frequent Magazine contributor.

![]()