Moon

Unit Zappa steps from the podium after reading to a large crowd

from her new novel, America the Beautiful. She is the

celeb author du jour, just the next in a procession that includes

the likes of Adam Gopnick, Salman Rushdie, Garrison Keillor,

and Jonathan Franzen.

Moon

Unit Zappa steps from the podium after reading to a large crowd

from her new novel, America the Beautiful. She is the

celeb author du jour, just the next in a procession that includes

the likes of Adam Gopnick, Salman Rushdie, Garrison Keillor,

and Jonathan Franzen.

Thirty

years ago big-name authors bypassed Portland, Oregon. And then

there was Powell's. Now the authors who come to the bookstore

for readings make sure they leave time for browsing.

"I

would like to move in here," sighs Zappa. "Just a

cozy spot. It doesn't have to be a queen-sized bed. If they'd

just let me hang out here."

It's

not the décor that draws authors, booklovers, and tourists.

The floors of the nondescript building-a former auto dealership-are

bare and the shelves simple. But those shelves are filled with

rows and rows of new and used books on four labyrinthine floors

that bibliophiles navigate with the help of color-coded maps.

Aptly named Powell's City of Books, the main store houses most

of the company's inventory of 1.5 million books.

This

is the bookstore that Michael Powell built: the largest independent

new- and used-book store in the world. Its foundations lie in

what was once a tiny student co-op in the Reynolds Club basement

at the University of Chicago. The co-op, which bought students'

books on consignment, became in the early 1960s a source of

spending money for Powell, then a graduate student in political

science.

He

was soon scouting neighborhood thrift shops for salable books,

lugging his prizes to the co-op by bike. Later he bought an

old car, just so he could carry more books. Every Sunday morning

he waited by his roomy 1955 Chrysler for the Maxwell Street

flea market to open, so he could fill the car with books for

the co-op.

Eventually

the spoils of his scavenging made up about one-fourth of the

store's inventory. When the manager left, he tapped Powell as

his successor. "He knew I had a stake in the store,"

says Powell.

Although

he already had a dissertation topic (the selection of Supreme

Court judges in Oregon), Powell came to realize he was more

entrepreneur than scholar. He managed the co-op for a couple

of years, then tried catalog book sales under the tutelage of

Joseph O'Gara, a Hyde Park bookseller from 1937 until his retirement

five years ago. One day in 1970 O'Gara suggested they share

a building at 57th and Harper. O'Gara would sell hardbacks;

Powell would sell paperbacks.

"I

said I would consider that, but I didn't have any money,"

Powell recalls. "He said, 'They want to talk to you.'"

"They"

turned out to be three U of C professors in the habit of playing

fairy godfathers to struggling Hyde Park bookstores. Sociology

professor Morris Janowitz, PhD'48, spoke for the group, which

included sociologist Edward Shils, X'37, and author Saul Bellow,

X'39, both from the Committee on Social Thought. The three floated

Powell a loan of $3,000, and Powell's Bookstore set up shop.

Years

later, Powell was ensconced in the front row of Portland's Arlene

Schnitzer Concert Hall, surrounded by other business and civic

leaders, all part of a sold-out crowd listening to a lecture

by Bellow. Someone in the audience asked, "Is it true you

started Powell's Bookstore?" Bellow's answer was quick:

"No, I didn't start Powell's Bookstore; Michael Powell

started Powell's Bookstore. I loaned him some money-and he paid

me back!"

Powell

remembers settling back into his seat with relief. "I thought,

'Thank God! I don't have to slink out of town.'"

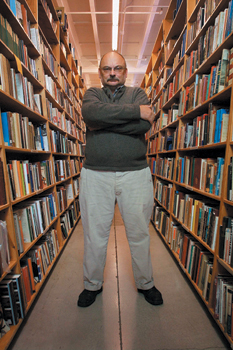

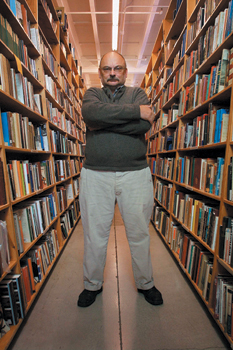

Not

likely. At 61 Powell-looking a bit like a stocky Vladimir Lenin

with his bald pate and beard-is so highly regarded in his hometown

that he is occasionally touted as the ideal mayoral candidate.

"I wouldn't have the tolerance," he scoffs. "I

have the inclination to tell idiots they're idiots, and that

wouldn't go over very well in politics." But with his stake

in the future of Portland and an educated citizenry, he embodies

the slogan inscribed on the town's oldest fountain: "Good

citizens are the riches of a city."

Powell

is a good citizen, contributing to the community as a businessman

and as a champion of literacy and First Amendment rights. A

former board member of the American Booksellers Association,

he was the treasurer of and continues to be active in the American

Booksellers Foundation for Free Expression. Closer to home,

he has served on the boards of the Portland School Foundation

and Multnomah County Library.

"We

have higher library use than almost any other place in the nation,"

notes Ginnie Cooper, director of the Multnomah County library

system. "I think one of the reasons we're so high-people

say it's the rain-but I actually think it's Mike Powell. He's

helped us be a city of readers, a city that values books and

knows they matter."

His

civic interests go beyond the literary. He is concluding his

second term on the Port of Portland Commission, which oversees

the airport, drydocks, marine facilities, and land development.

A board member of the Association for Portland Progress, he's

considered the engine behind some of the city's transportation

innovations: a light-rail line that goes from downtown to Portland

International Airport and a 4.7-mile streetcar line-the first

urban streetcar built in the United States in 60 years-that

just happens to pass his bookstore.

When

voters were faced in 1992 with the first of a succession of

anti-gay measures that targeted schools and school libraries,

Powell was a general in the battle to defeat it. "We turned

the bookstore into a billboard on that issue," he says,

raising more than $60,000 to fight the ballot measure through

sales of buttons and bumper stickers. He donates books to prisons,

children's homes, and charitable organizations. To date, his

company has donated books valued at half a million dollars to

local school libraries. In addition, he is a sponsor of Portland

Arts & Lectures, the series that brought Saul Bellow to

town.

Avin

Domnitz, chief executive officer of the American Booksellers

Association, describes Powell in the same terms most Portlanders

would use. "He has always considered himself a part of

the community, never above the community, even though the scale

of his operation has transcended what most independents in this

country have accomplished. He is a real contributor to the bookseller

community."

BY

1979 POWELL'S BOOKSTORE had taken over the entire

Hyde Park building originally shared with O'Gara (O'Gara's stayed

in business, moving several blocks west on 57th and then, as

O'Gara & Wilson, several blocks back east). Powell and his

wife, Alice Karlin Powell, AB'68, AM'78, a Montessori teacher,

might have stayed in Chicago forever. But his father, Walter,

who had run the Hyde Park shop one summer for his vacationing

son, had started his own used-book business, Powell's Books,

in Portland in 1971. Now it was Walter Powell's turn to ask

for help, and his son returned to Oregon.

BY

1979 POWELL'S BOOKSTORE had taken over the entire

Hyde Park building originally shared with O'Gara (O'Gara's stayed

in business, moving several blocks west on 57th and then, as

O'Gara & Wilson, several blocks back east). Powell and his

wife, Alice Karlin Powell, AB'68, AM'78, a Montessori teacher,

might have stayed in Chicago forever. But his father, Walter,

who had run the Hyde Park shop one summer for his vacationing

son, had started his own used-book business, Powell's Books,

in Portland in 1971. Now it was Walter Powell's turn to ask

for help, and his son returned to Oregon.

"He

had lost his lease, which seemed like a terrible thing at the

time," recalls Powell of the predicament facing his father,

who died in 1985. "But it actually gave me an opportunity

to put my imprint on a new store and be involved in that move,

the layout, design, and decisions. A year later we moved to

the current location."

That

location-1005 W. Burnside Street-was a square block that had

housed an American Motors dealership. Powell's Books used half

of the 40,000 square feet and leased the rest to various industrial

concerns, including a tow truck company. They eventually grew

into the whole building and then outgrew it. With the addition

of two floors to the building's north side in 1999, the main

store contains 98,000 square feet.

Powell's

decision to scrimp on décor, he says, merely shows that

he takes books more seriously than interior design. "I've

always thought the point here is to get the author's voice to

the reader's ear and be as invisible as possible in the process."

He wants his store to have the feel of a good library, the kind

of place where a person can literally get lost in the stacks-as

one man did a few years back. Engrossed in books, the reader

hadn't noticed that the store had closed. At 1 a.m. he called

Powell at home and asked the owner to get out of bed and come

let him out.

Many

travelers come to Portland just for Powell's; according to the

city's visitors association, it's second only to the International

Rose Test Gardens as a local tourist attraction. Some people

love the store's funky ambiance so much that they have chosen

to begin their married lives in its aisles, with wedding guests

squeezed among the bookshelves. There are those who say that

stepping into Powell's makes them feel like they've died and

gone to heaven, and indeed the bookstore is the final resting

place for one customer; his ashes were interred in the pillar-constructed

to look like a pile of books-at the store's north entrance.

"There's

a great deal of pride about Powell's and almost community ownership,"

Powell says. "Every once in a while a rumor goes around

that we're going to sell. It would be almost like selling City

Hall."

The

company's prodigious inventory is contained in the main store,

two warehouses, and seven satellite stores around town, including

a travel specialty store, a cooking and gardening bookstore,

a technical store, and two shops at Portland International Airport.

In Chicago he maintains half ownership of Powell's Bookstores,

which include the Hyde Park store, two other retail stores,

a wholesale division, and an annual trade show for buying and

selling remainders. When he moved to Oregon he turned the entire

operation over to co-owner Brad Jonas, X'80.

"When

Mike left, this was a great, solid, strong, scholarly used-book

store, but we have evolved," says Jonas. "I think

that's a strength of Mike's that he brings a lot of good people

together and then he gives them enough room to operate."

The

only problem with operating a bookstore named Powell's, says

Jonas, is that his customers expect him to have the same monumental

inventory as Powells.com, the Portland store's vast Web site.

Internet sales, 85 percent to customers outside the Northwest,

account for one-third of the entire Powell's Books business.

Online sales have doubled every year since 1994, when Powell's

technical store first put up a rudimentary site. Now the site

is almost ready to launch its first foreign-language editions,

in German and Spanish.

"The

site is known for a certain eclectic approach to books and a

slightly wacky feel," says Powell. With features such as

author interviews, staff recommendations, and book reviews from

Salon.com, Atlantic Online, and the Utne Reader,

it was listed in Forbes magazine's Spring 2001 Best of

the Web issue. Yahoo's e-shopping guide for 2000 called it the

best book site.

There

are no discounts, but Powells.com has what Amazon.com and Barnes

& Noble don't: a sea of used and out-of-print books. The

other two buy books from Powell's to fill their own orders.

Many

of the used books come from Powell's customers. Each store has

used-book buyers, with most of the 30 buyers at the Burnside

Street store. On an average day they buy 3,000 to 5,000 books

from walk-in sellers. Buyers are regularly dispatched to house

and estate sales and auctions, sometimes as far away as England.

The store also occasionally buys the complete inventory of a

used-book store going out of business.

"Michael's all about this. He sees himself as a used-book

buyer," says Michal Drannen, Powell's marketing manager.

Indeed,

at a book auction in Chicago, Powell landed a first edition

of The Whale, the title of Herman Melville's Moby-Dick

when it was published in Britain in 1851. Powell bought the

book for himself but is deliberately vague about its value-somewhere

between $50,000 and $100,000, he says.

Adventure

and sea stories have long been among his favorite books. He

still re-reads the Horatio Hornblower tales that ignited his

imagination as a child in Portland, where he was raised by his

Ukrainian father, a schoolteacher and painting contractor, and

his schoolteacher mother, who was from a long line of commercial

fishermen in Oregon. While in high school and as an undergraduate

at the University of Washington, Powell spent his summers fishing

on the Columbia River with his grandfather, earning spending

money by catching salmon, steelhead, and sturgeon.

These

days when he wants to get close to nature, he heads for the

high desert of eastern Oregon where he and his wife have a vacation

home they call the All Hat Ranch. (Their 22-year-old daughter,

Emily, lives in San Francisco.) The ranch's name refers to an

expression of disdain Texans have for weekend ranchers, people

who are "all hat and no cattle."

Powell

admits that he almost became more than a weekend rancher after

his 500-plus staff voted by a narrow margin to join the International

Longshore and Warehouse Union. The three-year contract they

demanded was signed in August 2000 after ten months of sometimes

bitter negotiations. The reserved, even shy bookseller, whose

wages and benefits were generous by industry standards, was

hurt that he was demonized in the process, depicted as a rapacious

bully, with some employees picketing and parading a life-sized

puppet of the boss around the store.

"One

of the things Oregonians pride themselves on is a certain civility

of conduct, a certain commitment to honest interaction,"

says Powell. "What I hated was the contentiousness of it,

I hated the personal vilification that's involved in the process."

Believing that his staff didn't need the kind of support and

protection that unions offer, Powell argued that he bent over

backwards to provide extra benefits and high wages.

Now,

he says, he has moved past the battle though the memories are

still painful."My greatest fear was that I would become

so disenchanted with the business that I wouldn't want to be

involved any longer. I thought that would be a tragedy of a

high order for myself because it's been my life."

Today

Powell's Books is back on an even keel. The aisles are filled

with book lovers every day of the year, and nearly every evening

a touring author gives a reading, often brushing shoulders with

other customers later while browsing for buys.

Alison

Dale-Moore, director of Powell's Rare Book Room, where the used-book

buyers' "finds" are displayed, was recently embarrassed

that she hadn't recognized the distinguished gentleman carefully

thumbing through the books. It was Salman Rushdie.

Not

to worry. Her faux pas can't top her boss's. Soon after Powell

had used the $3,000 loan to open his Hyde Park store, one of

his benefactors dropped by to put some books on hold. Powell

didn't recognize him.

"I

said, 'What name should I put it under?'" Powell recalls.

"And he said, 'Saul Bellow.' And I misspelled Saul. He

had to correct my spelling."

Susan

G. Hauser, AM'75, is a freelance writer in Portland, Oregon.

For 16 years she has been a regular contributor to the Leisure

& Arts page of the Wall Street Journal.

![]()

Moon

Unit Zappa steps from the podium after reading to a large crowd

from her new novel, America the Beautiful. She is the

celeb author du jour, just the next in a procession that includes

the likes of Adam Gopnick, Salman Rushdie, Garrison Keillor,

and Jonathan Franzen.

Moon

Unit Zappa steps from the podium after reading to a large crowd

from her new novel, America the Beautiful. She is the

celeb author du jour, just the next in a procession that includes

the likes of Adam Gopnick, Salman Rushdie, Garrison Keillor,

and Jonathan Franzen.  BY

1979 POWELL'S BOOKSTORE had taken over the entire

Hyde Park building originally shared with O'Gara (O'Gara's stayed

in business, moving several blocks west on 57th and then, as

O'Gara & Wilson, several blocks back east). Powell and his

wife, Alice Karlin Powell, AB'68, AM'78, a Montessori teacher,

might have stayed in Chicago forever. But his father, Walter,

who had run the Hyde Park shop one summer for his vacationing

son, had started his own used-book business, Powell's Books,

in Portland in 1971. Now it was Walter Powell's turn to ask

for help, and his son returned to Oregon.

BY

1979 POWELL'S BOOKSTORE had taken over the entire

Hyde Park building originally shared with O'Gara (O'Gara's stayed

in business, moving several blocks west on 57th and then, as

O'Gara & Wilson, several blocks back east). Powell and his

wife, Alice Karlin Powell, AB'68, AM'78, a Montessori teacher,

might have stayed in Chicago forever. But his father, Walter,

who had run the Hyde Park shop one summer for his vacationing

son, had started his own used-book business, Powell's Books,

in Portland in 1971. Now it was Walter Powell's turn to ask

for help, and his son returned to Oregon.