Home,

home in the Reg

>> Love

it or hate it, College students still live at the library.

For

Ray Gadke, the Joseph Regenstein Library is more than a building-it

is home. Every morning at 7 a.m., Gadke walks into the empty library.

Wearing his trademark Hawaiian shirt, he slips on his sandals,

reads the Chicago Tribune, and makes his rounds on the

third floor, turning on microform machines and tidying up tables

and shelves for the morning crowd.

For

Ray Gadke, the Joseph Regenstein Library is more than a building-it

is home. Every morning at 7 a.m., Gadke walks into the empty library.

Wearing his trademark Hawaiian shirt, he slips on his sandals,

reads the Chicago Tribune, and makes his rounds on the

third floor, turning on microform machines and tidying up tables

and shelves for the morning crowd.

Head

of the microforms department, Gadke, AM'66, has worked at the

library since it first opened in 1971, and after 30 years he no

longer notices the 4 million books or the 2,897 study spaces.

He sees the library in anthropological terms-as a microcosm of

the University. In this 577,085-square-foot cultural petri dish,

Gadke, a former social-sciences lecturer, studies the strange

behaviors, social patterns, and life of the College student.

More

than 804,000 students, faculty, and staff swipe through the library

turnstiles each year and, on average, 2,258 per day. That number

fluctuates from the busiest day, Tuesday-when up to 3,500 students

fill the library, cramming for exams and racing to finish papers-to

the slowest day, Saturday-when the same students, minds numb from

the week's work, will go anywhere but the library and do anything

but study.

There

are rumors around campus of students who never leave the library-those

who have found intellectual nirvana in the Regenstein's hidden

corners and now meditate on Plato, organic chemistry, and linear

algebra in straight 12-hours sets. But for the average student,

the library is less a temple and more a dorm away from dorm. Many

spend whole days there. Most have picked a favorite floor and

table and claimed them as their own.

What

is it about the library that moves so many to call it home? I

decide to find out, walking in Gadke's footsteps past the deeply

grooved limestone walls, through the turnstiles, and into the

world commonly known at the University as the Reg.

Among

the regulars on this particular Tuesday late in fall quarter,

Ben Carroll, a comparative-literature concentrator, finds his

spot on the fourth floor with practiced familiarity. "I practically

live at the Reg," explains the fourth-year. "It's my

one-stop place for socializing, napping, and researching. At my

dorm there's too much distraction. Harper's too social. And Crerar's

too quiet," he adds, dissing both the College's Harper Memorial

Library and the science divisions' John Crerar Library. "The

Reg has just enough distraction."

The

most tempting distractions are the plush sofa chairs by the windows

on every floor. Their soft red, blue, and gray seats beckon the

weary student. "Sleep," they seem to say.

A veteran library sleeper, Catherine Shim hears the call all the

time and says she responds all too often. Her favorite technique

is pulling together two chairs and catching blissful Zs between

the cushions. "But I can just fall asleep anywhere,"

says Shim, '03. "Tables are good too. You just have to make

sure you don't drool." And for that eventuality, Carroll

offers this advice: "If you put your sweater on top of a

Harrap's French dictionary, it makes a perfect pillow."

Demonstrating

a different technique on the fifth floor, Vikram Nidamaluri sits

before his laptop, head in his hands, closed eyes still facing

the screen. He has fallen asleep writing a paper due the next

day. When he wakes up, the first-year smiles wanly and explains,

"I haven't slept the last two days…tonight I'm averaging

30 minutes per paragraph, so just two more hours and I'll be done."

The

fifth floor has a reputation for hard-core students like Nidamaluri.

Offering texts from distant Asian countries, the floor itself

is an exotic land. During final exams, students' desks seem more

like makeshift dorm rooms, complete with personal minilamps, alarm

clocks, blankets, and pillows.

Yuh

Wen Ling, a die-hard fifth-floor fan, sets up her cubicle with

a laptop, CD player, headphones, and fluffy jacket for a pillow.

"But I'm not that bad," the third-year whispers, pointing

to others around her. "I know some on this floor who even

keep a change of clothes and toothpaste in their lockers."

The

beige lockers, stacked four high, stretch in long rows throughout

the library. Each stands about seven books high, 20 books wide,

and five deep, but even that's not enough for Colleen Daly, who

is considering a second locker. She seems slightly embarrassed

as she turns the latch to reveal a cubby overflowing with texts.

She rented the $4-per-year locker when she started on her B.A.

thesis over summer. With the thesis due soon, Daly, '02, has studied

in the Reg every day of fall quarter, holing up in her favorite

cubicle with a stack of books. Staring at the piles still waiting,

Daly sighs, "There are definitely times when I feel like

I should be doing more."

Like

the smell of books, such guilt seems to permeate the Reg's atmosphere.

With computers, friends, and sofa chairs conveniently near, students

are always just an e-mail, conversation, or nap away from procrastination.

Alejandro Ortiz, another library regular, says guilt is useless

and unproductive. He considers himself a guru of sleeping and

studying at the library-skills he's been developing since high

school. "When I fall asleep studying, I wake up automatically

in 20 minutes," he says. "It's like my body just knows

I can't afford to miss time."

An

orderly person who keeps his glasses wiped clean and his hair

brushed in neat lines, Ortiz has strict study habits. He sets

up books, fruit, and a water bottle at his table and checks e-mail

beforehand so he won't have excuses to get up. After three years

in the College, Ortiz has his cramming formula down pat. "Past

18 hours of work, the perfect nap is an hour and 15 minutes,"

he explains. "Your learning curve decreases the more sleep-deprived

you get."

Like

most students, Ortiz describes his chosen study spot in personal

terms. "I'm a third floor kind of guy," he says. The

third floor represents a compromise-a Taoist balancing of priorities.

"It gets quieter the higher you go up, but the pretty girls

are usually on the lower floors."

Walking

through the different levels, I see the Reg's social pockets unfold

like layered civilizations in an archaeological dig. History graduate

students pore over their research on the third floor. Members

of the Greek system dominate the second. On the first floor a

group of Asian students discusses its migration this year from

the second floor. "A little noise is good," says one.

"Two's always been overrated anyway."

The

basement's upper floor, A-level, is mostly filled with economics

majors and business school students. For every person who passes

through the double-door entrance, students glance up from their

books, and the new entries are either dismissed or filed away

for future reference. Longtime A-leveler Dan Egel, '02, notes,

"The girls are always looking at the guys, and the guys are

definitely looking at the girls."

The

library has always been the social center of the campus, says

Gadke-who was a graduate student when the Reg first opened-"so

it becomes the arena when people want to deliver a message or

want an audience." During the student protests in the 1970s,

he recalls people pulling fire alarms almost every day, and every

spring fraternity pledges streaked naked through the library.

In the 1980s there were reports of a shoe thief prowling the Reg,

preying on students who removed their shoes to study. According

to Gadke, when police eventually caught the culprit, they found

his apartment overflowing with footwear.

In

the most recent prank library staff remember-besides the track

team's annual streaking, which they try to forget-two years ago

students sneaked in small chickens and set them loose on the third

floor. Tyjuan Edwards, who was working at the circulation desk,

remembers seeing the little balls of fluff. "I didn't have

to catch them myself," says Edwards. "Not that I'm scared.

I just don't like grabbing livestock."

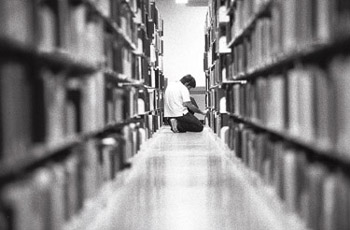

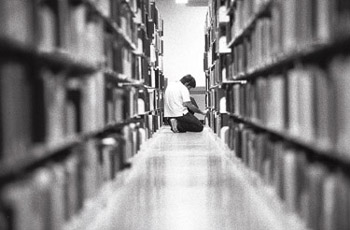

Study

purists, who shun this social side of the Reg, find refuge in

the book stacks on the west half of every floor but the first.

The stacks' abandoned rows of books are ghostly silent, except

for the steady hum of the ventilation. Student worker Angela Zielinski

is one of the few inhabitants of this dark underworld. The second-year

glides between rows, jamming to her headphones while shelving

returned books. "At night it gets a little creepy because

it's so quiet and dusty," she admits. "But you get a

lot of time to think. I work on math problems while shelving.

I take Attic Greek too, so sometimes I decline nouns in my head."

Every

year the library system hires 235 student workers like Zielinski

to do everything from cataloguing new books to uploading scanned

texts. Most jobs pay $8.67 to $9.27 an hour, but some, requiring

specialized skills such as language translation, cross the $10

mark.

The

book stack department hires the most students, 45 per quarter,

and for the long-distance shelver the job can often be depressing

and lonely. Full-time managers give frequent pep talks to motivate

student workers and encourage shelving together to ward off boredom.

"It can be a depressing job because the books just keep coming

and never end," Zielinski says. "You have to remind

yourself that what you do is important…. It's like Plato-shelving

is for the common good, for the good of the state."

Over

time the job becomes a test of the soul and will. For some, long-term

exposure makes them indifferent to the cause. For others, the

work becomes an almost sacred task. "For people with obsessive-compulsive

tendencies like me, it's a perfect job," says Zielinski.

"I think of myself as the guardian of books."

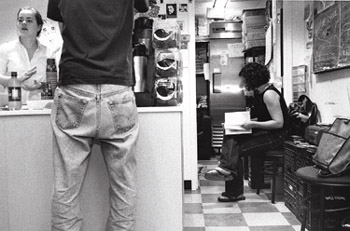

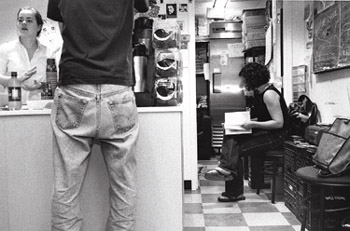

If

shelvers are the Reg's sacred guardians, workers at Ex Libris

are the sacrilegious jesters. Manager Lauren Kroiz says the student-run,

University-funded coffee shop is much more than a business. "I

don't know if it's really a charity, business, or support group,"

says the fourth-year art-history concentrator. "It's like

a club where people come to hang out." Most of the staff

show off their Ex Libris pride by wearing the shop's eX logo on

backpacks, pants, and T-shirts. White and gray eX socks dangle

from the door, a handwritten sign offering them for $2 a pair.

Located

just below the lobby, the eccentric café is covered with

other quirky, homemade signs. A Polaroid by the Thai food shows

an employee squished onto the bottom rack of the fridge. The caption

reads, "Where are your children right now?" Another

sign in orange and black warns, "What if napkins were made

of people?!?…YOU COULD BE NEXT!"

The

shop is famous for its edgy personality, says Cian O'Day, who

has worked there for two years. "We pride ourselves on giving

our customers a little attitude. I mean, what's more memorable:

a 'please' and 'thank you' or throwing a curveball in their day

that will stick in their minds?"

Some

of the curveball pranks have become legendary among employees.

O'Day, a history concentrator, opens the file cabinet to show

a Saran-wrapped plastic cup labeled "Gene's soul." He

explains that bored employees once advertised free food for customers

willing to sell their souls. "We ended up getting eight or

11 souls before we got in trouble with the manager," says

the fourth-year. "Needless to say, most of the signers were

people from the B-school and Law School."

"But

it's all serious work now," claims O'Day, while another employee

smirks and shakes her head behind him. The conversation among

staff slowly drifts to faith in God and disillusion with society

to boyfriends and strange customers.

"We talk about the customers a lot," admits Susan Catapano,

a second-year employee. "Everyone knows Decaf Guy,"

she says, referring to a customer who exclusively buys raisins

and decaffeinated coffee. "Then there's Excessively Meek

Woman, The Three Nice Ladies, and Medium Man."

"And

Quarter Man," adds O'Day. "He buys one bagel, takes

like 14 things of cream cheese, and wants all our new quarters…you

know, the ones with state landmarks. But he's really nice-nice

but eccentric."

The

description fits the employees just as well as the customers.

The workers find themselves at the shop-even on days they don't

work-just to hang out and check in with their friends. Relaxing

in a chair in the back room, Catapano explains, "The library

is my home. This is just my living room."

![]()

For

Ray Gadke, the Joseph Regenstein Library is more than a building-it

is home. Every morning at 7 a.m., Gadke walks into the empty library.

Wearing his trademark Hawaiian shirt, he slips on his sandals,

reads the Chicago Tribune, and makes his rounds on the

third floor, turning on microform machines and tidying up tables

and shelves for the morning crowd.

For

Ray Gadke, the Joseph Regenstein Library is more than a building-it

is home. Every morning at 7 a.m., Gadke walks into the empty library.

Wearing his trademark Hawaiian shirt, he slips on his sandals,

reads the Chicago Tribune, and makes his rounds on the

third floor, turning on microform machines and tidying up tables

and shelves for the morning crowd.