A

Run for Our Money

>> Before

the bubble finally burst...the

numbers reported by a handful of universities almost strained

belief.

Duke

averaged annual investment returns of 33 percent for three straight

years, growing its endowment from $1.8 billion to $3.6 billion

between 1998 and 2000. Notre Dame increased its holdings by an

amazing 59.7 percent in 2000; its endowment went from $1.2 billion

to $3.2 billion in just three years. Harvard, with a more modest

rate of return of 36.1 percent, brought in more than $5 billion

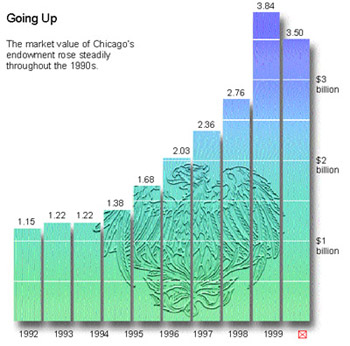

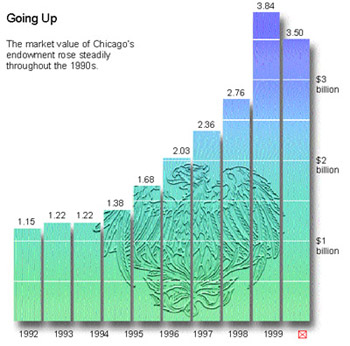

in a single year. And the University of Chicago, with a 40.9 percent

rate of return for the year, socked away $1 billion in investment

returns between June 1999 and June 2000, bringing its total endowment

to more than $3.8 billion.

The

financial press was agog. Universities weren't the slow-moving,

overcautious investors they'd been for decades. Instead, especially

in the elite circle of billion-plus endowments, they emerged in

the 1990s as among the smartest and most sophisticated of institutional

investors. In the world of venture capital they were everywhere,

and many made remarkable returns.

When

the bubble burst, as everyone knew it would, there was no question

that universities would take a hit. But how much? The strategies

that led institutions into venture capital and other nontraditional

investments were designed not just to take advantage of events

like the high-tech run-up of the 1990s. They were also supposed

to render the endowments safer from market downturns by diversification.

This spring, anticipating the release of preliminary data from

the two annual surveys of university endowments, observers waited

to see how well those strategies had worked. Would the combination

of a battered domestic stock market and a train wreck in venture

capital drag the universities down, or would the same tactics

that had produced colossal returns for the past four or five years

pay off now by protecting endowments from the beating so many

investors were taking?

When

the survey numbers were released by the National Association of

College and University Business Officers (NACUBO) and the college

and university investment service Commonfund, the news was not

bad at all. Yes, endowments were down, a bit more than 3.5 percent

across the board. Of the 41 schools reporting billion-plus endowments

in 2000, all but six lost ground-the first time a substantial

number of university endowments had experienced a loss since 1974.

But in the same period the Standard & Poor's 500 stock index

was off 14.8 percent. Among the billion-plus institutions-those

most likely to have engaged in sophisticated portfolio tactics-the

average drop, according to NACUBO, the more comprehensive of the

surveys, was only 1.6 percent, a remarkable achievement in a dreadful

market. Even among the harder hit, including Chicago-which lost

8.6 percent, mainly through losses in private-equity investments-the

results were still substantially better than the stock market.

Long-term

returns, the ones that really count to university investors, were

holding in well above the 10 percent or so that many institutions

look for. Chicago, for instance, had five- and ten-year average

returns of 16.4 percent and 14.2-a respectable performance and

one that probably understates how well the University's investment

strategy is doing today, in the wake of a series of changes that

began in 1998. The value of Chicago's endowment was $3.5 billion

as of June 30, 2001, the end of the most recent fiscal year. As

of January 1, 2002, it was at $3.2 billion-still a dramatic improvement

over the mid-1990s, when the endowment was only about $1.5 billion.

No

one denies that 2001 was hard. At the same time it marked a giant

step for higher education. Universities missed out on the bull

market of the 1950s; they lost their shirts in the 1970s. But

thanks to a process of evolution that's been in the works for

the past 25 years or so, they've left the roller coaster of the

late 1990s comfortably ahead of the game.

THE

REVOLUTION STARTED in the 1960s. Until then, the typical

university endowment was invested in bonds and stocks chosen for

their ability to pay dividends, not for growth potential. The

institution held on to the principal and spent the income. It

was the way things had always been, but in the face of inflation-and

a bullish stock market-one major donor to university endowments

was up in arms. "The Ford Foundation saw the real value of

investments declining," explains John Kroll, who as the University's

associate comptroller is in charge of endowment accounting. "A

fund that would pay for 20 scholarships a year in 1920 was only

paying for two by the 1960s." Ford issued an influential

report urging universities to put more of their money into growth

stocks and to adopt rules that would let them pursue a "total

return strategy," taking advantage of market appreciation

as well as interest and dividends.

The

proposal was smart-but not necessarily legal. Endowments were

governed by trust law, and under trust law it wasn't clear that

universities were allowed to put endowment principal into risky

stocks, even as part of a diversified portfolio, or that they

would be allowed to spend money earned through appreciation. In

most states it was illegal for an institution's trustees to delegate

the power to make investment decisions.

The

legal problems were essentially solved by the Uniform Management

of Institutional Funds Act, a model law submitted to the 50 states

in 1972 and since adopted by all but a handful. It set the stage

for schools to dive into the ebullient, fast-growing stock market.

And dive some did-just in time to get whacked by the bear market

of the 1970s. The combined endowments of the Ivy League plus Stanford

and Chicago, measured in constant 1967 dollars, were worth $3.16

billion in 1971-72. A year later they had dropped to $2.2 billion,

and they continued to erode slowly for most of the decade.

Although

burned, universities didn't turn back. Over the next few years,

they cranked up the horsepower of their investment committees,

hired talented managers, and drew on the investing expertise of

trustees and alumni.

The

goal was diversification. If the 1960s proved that a portfolio

of bonds wasn't sufficiently diversified, the 1970s proved the

same for stocks. The savviest investors started looking for other

places to put their money. One of the first places they turned

was to venture-capital funds. These companies, which let investors

take a stake in a pool of start-up businesses, were a good fit

for well-connected, long-horizon players like universities. Persuading

trustees took effort, says William Massy, an economist who saw

the process firsthand as vice president of finance at Stanford

in the 1970s. "We had a lot of discussion with our board

before we were allowed to do these things. Early on it was a problem,"

he explains. "These things were not liquid, you were tying

up your money for seven years or more, and it was also difficult

to determine what the real market value of these portfolios was.

It was really a finger-in-the-wind kind of thing and had to be.

But we got past all of that."

If

universities embraced venture capital-and natural resources, hedge

funds, and much more-it's partly because, for a while at least,

everything worked. "You saw a bull market in the '90s like

you'd never seen before," says John Griswold, a senior vice

president at Commonfund and executive director of Commonfund Institute,

the organization's research and educational arm. "You had

a good bond market, a good stock market, almost anything you did

with equities or bonds was pretty good, and in some cases absolutely

phenomenal. Venture, private equity, emerging market debt, were

all pretty marvelous places to be. If you stuck with it and did

your rebalancing religiously, so that you took some off the winning

bets and put it on the laggards, you really did well." The

trick was to diversify, with investments that didn't correlate

with each other. It's an idea that Griswold jokingly calls the

"free-lunch principle," but it's better known as Modern

Portfolio Theory, and it was first developed (in a place with

a long suspicion of free lunches) as the dissertation of Harry

Markowitz, PhB'47, AM'50, PhD'55, a future Nobel Prize winner

then pursuing his doctorate at Chicago.

UNIVERSITY

FOLK OFTEN talk about endowment as if it were a distinct

financial entity-a pot of money in the president's office to be

cautiously dipped into from time to time. The reality is much

messier. Take Chicago's endowment: it consists of 2,200 separate

funds, each with its own purpose and rules and history. The biggest

is the $410 million Rockefeller General Endowment Fund, the direct

descendant of $14 million of the $35 million in contributions

made by John D. Rockefeller between 1889 and 1915.

Some

funds are free to be used as the University wishes. Others have

extremely specific purposes. One of the smallest ($4,128.84) was

established by a gift of $250 in 1912 to provide a prize for the

student earning the largest number of points at the Intercollegiate

Track Meet (or, today, its historical successor, the University

Athletic Association conference championship). Though the funds

are pooled for purposes of investment, they have to be accounted

for individually to ensure that donor wishes are followed and

that principal is kept intact. Of Chicago's $3.5 billion, $592,766,000

can never be spent-including exactly $13,858,833.04 of the Rockefeller

fund.

Rather

than allow individual programs, departments, or schools to manage

their own investments, most universities put all their endowment

money-and occasionally other funds that the institution has decided

to treat as if it were part of the endowment-into investment pools.

The University of Chicago's, created in 1972, is called the Total

Return Investment Pool (TRIP). A sort of in-house mutual fund,

TRIP and the endowment are almost, but not quite, synonymous:

TRIP includes some funds not considered part of the University

endowment. The divisions and schools own shares in TRIP, receiving

annual payouts based on the size of their stakes.

Chicago

calculates payout with a formula used by many universities: 5

percent of the average value of the endowment over three years,

skipping the most recent year. Five percent was the figure recommended

by the Ford Foundation in its original proposal for endowment

reform-chosen to approximate the yield of bonds at the time. Over

the years 5 percent has proven to be just about on target as a

figure that maximizes payout while protecting the endowment's

real buying power.

In

2001 revenue from Chicago's endowment accounted for 10.7 percent

of its operating budget. That's up from 7.5 percent in 1991 as

a result of both new gifts and growth of the value of TRIP investments,

but there is still room to improve. At Yale endowment revenue

was more than 20 percent of the budget in 1999-2000, compared

to about 10 percent a decade earlier. Harvard's budget last year

included about 30 percent endowment revenue, and Princeton's an

enviable 37 percent.

How

well TRIP performs is the daily concern of the University's 15-person

investment office, tucked unobtrusively into the Gleacher Center,

the downtown facility of the Graduate School of Business. Chicago

hasn't gone as far as some of its peers in making the investment

office independent (Harvard, Duke, and others have spun their

investment offices off as separate, wholly owned businesses, partly

to enable them to pay the salaries demanded by top investment

professionals), but there's a bit of symbolism to the location:

off the main campus, away from the administrators and faculty

who depend on the office for a share of their budget, almost invisible.

The

man who presides over the operation, vice president and chief

investment officer Philip Halpern, came to Chicago in July 1998

after a stint as treasurer at the California Institute of Technology,

plus four years of managing $35 billion in investment and retirement

funds for the Washington State Investment Board. His appointment

was part of a broader set of reforms designed to improve the efficiency

and quality of the University's investments.

Phase

one of the reform had come a few years earlier-a drastic reduction

in the size of the trustees' investment committee. The committee

had been one of the larger trustee committees ("It beat the

audit committee," jokes Halpern). Stripped down to a handful

of people with investment expertise, its current membership includes

chair James Crown, general partner in Henry Crown and Company;

Andrew Alper, AB'80, MBA'81, former managing director of Goldman

Sachs and now president of the New York City Economic Development

Corporation; John Corzine, MBA'73, U.S. Senator from New Jersey

and former co-CEO of Goldman Sachs; Richard Franke, retired chair

and CEO of Chicago's John Nuveen Company; Eric Gleacher, MBA'67,

a New York-based investment banker perhaps best known as the founder

of the merger-and-acquisition department of Lehman Brothers; and

J. Parker Hall III, chair and managing director of New Salem Capital,

L.L.C. The nontrustee members are David Booth, MBA'71, chair and

CEO of Dimensional Fund Advisors, and Martin Leibowitz, AB'55,

SM'56, chief investment officer for TIAA-CREF, the world's largest

managed investment fund.

Phase

two, which began when Halpern arrived, was to shift the office

away from hands-on management. "Prior to my arrival, the

investment office did all the security selection in-house except

for a few private partnerships," Halpern explains. "We

did all of our bonds, we had two real-estate professionals that

would go around the country buying properties, and we had stock

portfolio managers. And the performance was OK, it wasn't stellar,

it wasn't terrible, it was OK."

Direct

management has become fairly rare among the largest university

endowments, and for good reason. It's labor intensive, and if

you want good results, you have to hire some very expensive talent.

Harvard, the school with the most vigorous commitment to direct

management, has an investment staff of close to 200, and it has

an incentive system that has resulted in some of the managers

being paid enormous sums (a year ago three managers were paid

more than $10 million each) to the ongoing distress of many faculty

members.

Far

more common among the big endowments is the strategy Chicago uses.

The investment committee develops a plan for asset allocation-that

is, it decides how much of the endowment will go into stocks,

how much into bonds, how much into venture capital, and so forth.

The investment office then works with outside managers to place

the money according to the plan.

In

placing the funds, Halpern follows what he calls a "barbell"

strategy, concentrating on low-risk and high-risk, high-effort

investments and generally staying away from areas in between.

The strategy is all about resources; Halpern wants to avoid putting

effort into areas where effort isn't likely to improve performance.

"We're very, very conservative in certain areas where we

don't have a competitive advantage," he says. "Our bond

portfolio is almost all treasury and agency bonds. We don't take

credit risks, we don't invest in corporations. Our U.S. equity

portfolio is mostly indexed." The strategy frees up staff

time and energy to explore areas where Chicago has a potential

advantage-mostly in so-called "alternative" investments,

including venture capital, private equity, hedge funds, and the

like.

"Advantage"

to Halpern comes down to three things: Chicago's reputation, its

expertise, and the investment committee's newly slimmed-down governance

structure, which allows fast decision making.

All

three are important, but in the vital game of hiring the best

managers and joining partnerships with the best returns, reputation

is especially vital. "Most of the best managers don't want

all the money they can attract," explains trustee and investment

banker Eric Gleacher. "Their performance goes down if they

take in too much. So they close up." Universities, with their

financial expertise and long investment horizons, have a real

advantage in getting through the door. The elite schools have

an extra chip to play: "The managers use us when they go

out and do their deals, saying, 'Look at our investor base-we

have Yale, we have Chicago, we have Stanford.' We put a stamp

of credibility on that firm."

Getting

into the best partnerships and working with the best managers

is important, but according to William Massy, "Virtually

all of the investment gurus now say that the bulk of variation

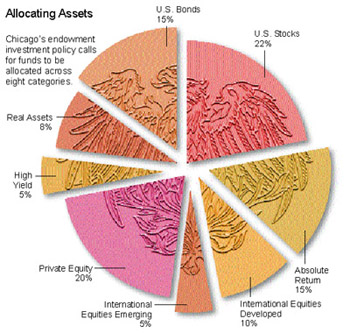

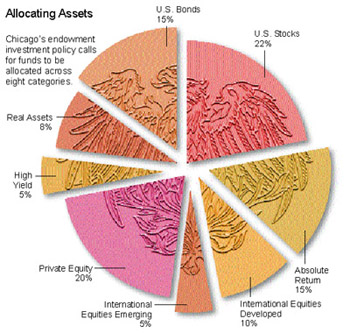

of returns these days comes from asset allocation." Chicago's

allocation, like those of most of its peers, has grown more complex

and diverse. When Halpern arrived the endowment was about 45 percent

U.S. equities (a high figure for an endowment Chicago's size).

Bonds were about 15 percent, while international investments,

real estate, private equity, and natural resources each accounted

for about 10 percent. Today U.S. equities are down to 22 percent

of the endowment. That one decision to reduce equity exposure,

which was implemented during market peaks, saved the University

$150 million.

Private

equity is up to 20 percent, while international equities, absolute-return

investments (a form of hedge-fund investment that brings predictable

and consistent shorter-term returns), and U.S. bonds each make

up 15 percent. The rest consists of real assets like natural resources

and timber and high-yield bonds. Overall, again like its peers,

Chicago has chosen a strategy of giving itself more opportunities

to lose money-and more opportunities to win big.

IN

A 1990 ARTICLE

in the University of Chicago's Journal of Legal Studies,

Henry Hansmann, a Yale law professor who studies the economics

of nonprofit institutions, took a skeptical look at the very concept

of university endowments. Why did universities save so much of

their income instead of spending it more or less currently? One

common answer to that question, he said, is the idea that endowments

preserve intergenerational equity-we shouldn't rob from our children

and grandchildren to support ourselves. But does that argument

hold up? "There is every reason to believe that, over the

long run, the economy will continue to grow in the future as it

has in the past and that future generations of students will therefore

be, on average, more prosperous than students are today, just

as today's students are more prosperous than their predecessors,"

he argued. "[I]t would seem more equitable to have future

generations subsidize the present"-perhaps by encouraging

universities to borrow rather than save.

Hansmann's

ideas were challenging, but not even he expected universities

to start spending their endowments anytime soon. The reason is

partly a matter of economics: if you could make 10 percent

a year on your investments and borrow at 5 percent, how likely

would you be to pay for essentials by selling off your portfolio?

A more important cause has to do with human nature and institutional

habits and talents. Donors like the idea of perpetuity: Tell a

John D. Rockefeller that you plan to spend his millions on a yearlong

outburst of teaching, learning, and research like the world has

never seen, and he'll show you the door. Tell him you can make

his money immortal, and he's hooked. Considering what his money

can accomplish and what it can grow into over the course of a

century or more, hooking him is a goal well worth pursuing.

Universities,

for their part, are brilliant at creating things to do with money.

They're much less good at making hard choices between those things.

(Ask any administrator at budget time.) The endowment system both

encourages and discourages risk taking. (Can we have a new professorship?

Sure, but it will cost two million dollars up front. Has our research

in X come to nothing? No problem, we didn't spend any of the principal.)

The economist Howard Bowen, who also served as the president of

three very different educational institutions-Grinnell College

in Iowa, the University of Iowa, and California's Claremont Graduate

Center-is remembered for "Bowen's Law," which described

the economics of higher education as a matter of converting money

into goods like knowledge, learning, and reputation.

Left

to their own devices, universities will inevitably follow the

boiled-down formulation of the law that's a watchword among higher-education

economists: they raise all the money they can and spend all they

raise. The endowment system, with its focus on preserving spending

power in perpetuity, adds some discipline to the process-and a

safety net.

Thus

endowments will continue to be an essential part of an institution's

financial life and an important yardstick in measuring institutional

prestige and power. Size has its benefits. In the three-year period

from 1999 to 2001, schools with billion-dollar endowments had

an average investment return rate of 12.8 percent. The average

for all schools was 6.7 percent. Likewise, while the billion-plus

club lost 1.6 percent on its investments last year, the average

institution lost 3.6 percent.

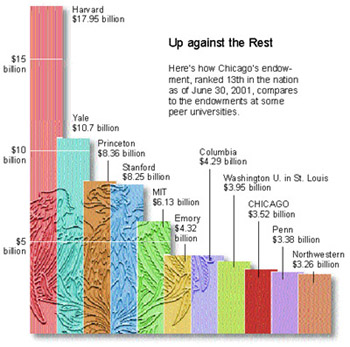

For

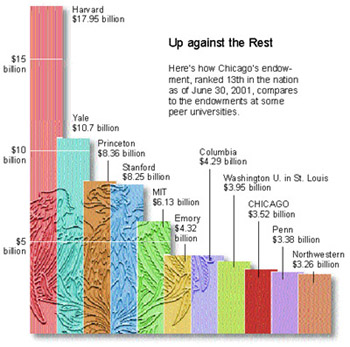

its first 50 years Chicago had the largest endowment of any U.S.

university. Today, its $3.5 billion puts it in the same league

as Rice, Duke, Penn, Northwestern, and a half dozen others. Ahead

are Columbia's $4 billion, MIT's $6 billion, Stanford and Princeton's

8, Yale's 11, and Harvard's 18.

"It's

one thing to have 3 and a half billion. It's another thing to

have 20," says Eric Gleacher. "To be on the cutting

edge of research and intellect in the world you need capital.

And I think that's one of the reasons American education is unique.

You go to the U.K. or Europe and private support for universities

is almost nonexistent. That's why they don't have the same educational

system we do. Funding is important. And having an endowment where

you maximize the investment proceeds is important."

"I

think the overall job of the trustees is to oversee the University

on an intergenerational basis, so its quality, its mission, and

its service to the academy-and even more broadly to the world-are

maintained," notes investment committee chair James Crown.

"While other parts of the University are busy trying to build

intergenerational intellectual capital, the intergenerational

financial capital of this and all universities resides in the

endowment. People describe it many ways, as the University's bank

account, as its safety net, as its allowance, as the undergirding

for current spending. But the bigger it is the safer and more

flexible the University is."

And

so, back at the Gleacher Center, Philip Halpern and his staff

are diligently maximizing. There's a new investment in Russia,

the University's first, that seems to be doing well. "Knock

on wood, we timed it right," says Halpern. "It's gone

up about 25 percent in just about seven weeks. It could go down

too." The private-equity component is down again, a huge

write-off. The hedge funds are turning over a steady 1 percent

a month. There are partnerships to look at, due diligence to perform,

the allocation to fine-tune.

"Investment

is very simple," says Halpern. "You're just playing

with probabilities. And you try to increase the probability of

doing well and decrease the probability of things going badly.

But you're never going to be 100 percent right, and you're never

going to eliminate all risk. Sometimes you're going to toss the

coin, and it's going to come out tails. You decide what your discipline

is, and you try to keep with it, and hopefully it will pay off

in the long run."

Patrick

Clinton is a freelance writer in New Jersey, the former editor

of University Business magazine, and the father of Daniel

Clinton, '05.

![]()