|

|

|||||||||

|

Is there a plot in this plat?

Students in Kathleen N. Conzen’s urban-history colloquium take a questioning look at the old neighborhood.

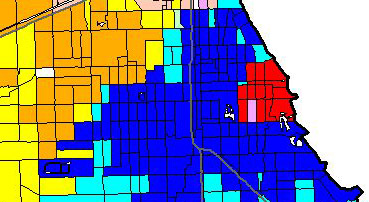

History 296, Colloquium: Chicago and the South Side, meets in JRL 130, a windowless seminar room in the Special Collections wing of the Joseph Regenstein Library. The room assignment makes logistical sense. One goal of Kathleen Neils Conzen’s course is to “introduce students to the methods and sources of historical research.” Proximity to the Reg’s resources means that field trips—to the University archives, for example—are quick commutes. Students also have a quick commute to the colloquium’s topic: the relationship between the University and the neighborhood and city in which it is located. In using Hyde Park and the South Side as a case study to introduce issues and methodologies in the history and historical geography of American urban life, Conzen teaches close to her own specialty, 19th-century U.S. social and political history. With a Ph.D. from the University of Wisconsin–Madison, she is the author of Immigrant Milwaukee, 1836–1860: Accommodation and Community in a Frontier City (Harvard, 1976). Completing a book on 19th-century German-American efforts to develop and defend a theory of pluralistic democratic nationalism, Conzen, a 1995 Quantrell Award winner for excellence in undergraduate teaching who chairs the Department of History, is also finishing up a book on German peasant settlement in the frontier Midwest. On a Tuesday afternoon in late October, Week 5 of the quarter, students enter the seminar room, conversing in low, library tones as they take seats and pull out the day’s assigned reading, paper, and pencils (Special Collections is an ink-free zone). Conzen arrives in shades of black and gray and reminds the class that the day’s agenda, Urban History in Microcosm: A University and Its Neighborhood, has been altered to include Week 4’s practicum, Interpreting Maps and Other Visual Sources. Waiting for a few stragglers, Conzen makes light conversation with the students already in their places: “I hope you all have been starting to have some adventures in the archives.” Then they set off for the third floor. Minutes later Christopher Winters, the Library’s bibliographer for anthropology, geography, and maps, stands before a worktable covered with colorful charts—a small sampling of the 400,000 maps, 10,000 air photos, and 2,000 books that make Chicago’s one of the largest university map libraries in North America. Winters is recovering from a cold, but his hoarse voice lilts with enthusiasm as he displays samples of the collection’s wares. First up is a 2003 Rand McNally map of Chicago. “These are in some ways just awful from a scholarly point of view,” he says, noting for example that “there’s a Veterans’ Hospital in my neighborhood that was torn down 25 years ago—it’s still on the map.” Next comes a 1957 map of the Chicago area distributed by Phillips 66, with the firm’s orange-and-black logo prominently placed. “No public transportation routes are noted,” he explains, “because gas companies couldn’t care less.” Picking up another sheet, he encourages the students ringing the table to examine more closely the one he’s just put down: “Maps are meant to be looked at.” For the next half-hour the group does just that, seeing Chicago charted and recharted. Topographic maps, air photos from the 1930s, 19th-century fire-insurance maps with structures color-coded pink, blue, green, or brown to show the building materials used, plat maps marking property boundaries. “Some of you are going to work on urban renewal,” Winters says, introducing the collection’s holdings in that area, including Chicago’s 1946 comprehensive city plan, with its “freeway on the West Side that never got built,” and maps from the 1960s urban-renewal period with housing projects delineated in somber reds and browns. He calls up a 1990 land-use map on the monitor behind him: “You can customize it any way you want—up to a point,” noting that the basic tract files can be overlaid with one’s own research. “Cool,” a guy in jeans responds, seeming to speak for the group, and a flurry of nuts-and-bolts questions and answers about downloading ensues. It’s on to thematic maps: tracking patterns of ethnicity, land use, economic strata, transportation use. “Anything that varies,” Winters tells the historical-geographers-in-training, “can be mapped.” Back in JRL 130 Conzen asks her students to introduce themselves to a visitor, introductions that do double duty as quick reports on the topics they’ve chosen for the course’s capstone paper. Formal presentation and defense of a three- to four-page research proposal, including research design and bibliography, are due Week 7. Clockwise around the seminar table the ten men and three women reel off their names and subjects. Some zoom in on a building or event: Why did the Chicago Housing Authority place the Cabrini Green housing development so close to the wealthy Gold Coast? What role did civil rights and race issues play in the 1966 Douglas-Percy race for the U.S. Senate? Others soar out in a bird’s-eye query: Will tracking the migration patterns of the city’s Polish population over the last century show that immigrants from specific regions congregated in certain Chicago neighborhoods?

Several topics blend town and gown: How does the history of Woodlawn’s First Presbyterian Church and its agenda of social engagement relate to the history of the U of C? How does the Shoreland’s shift from elite hotel to undergraduate residence mirror the University’s relationship with the Hyde Park neighborhood? Circle completed, Conzen signals a turn. “Moving from the broad scale of the city of Chicago, and bringing it down to Hyde Park,” she shifts to the day’s reading. Part of Arcadia Publishing’s Images in America series, Hyde Park, Illinois, by Max Grinnell, AB’98, AM’02, is a selection of captioned photographs and drawings. “Let’s start with a bit of general reaction,” Conzen urges. With customary hesitancy, students flip through pages, gathering thoughts. “It’s just letting pictures tell the story,” comes the first venture from a young man in a red and white long-sleeved T-shirt. “It’s basically captions,” a guy across the table agrees. “Do the pictures tell you anything here?” Conzen presses. “They raise a lot of questions?” one student tries. Another compares reading the book to “watching a slide show.” Grinnell’s book is part of a series, Conzen acknowledges, with a “fixed format—lots of pictures and relatively small text, aimed at a popular audience. For all of that, this book does have an argument, a thesis, a plot.” In other words, she asks, “Is there a point that Grinnell wants to make?” The discussion takes off as the class moves from Grinnell’s perspective as a U of C student looking out at the neighborhood to his definition of Hyde Park—from 51st Street to just south of the Midway, from the lake to Drexel or Cottage Grove. They note that he divides his history into three periods: up until the 1893 World’s Fair, from the fair until the 1950s, and the start of urban renewal—rise, decline, and rejuvenation. For Grinnell, Conzen sums up, Hyde Park is the story “of the University that built a neighborhood but then could have done more.” Again the scale shifts as Conzen asks students to share observations from the week’s practicum assignment: selecting a two-block area of Hyde Park and walking it slowly, “looking carefully at everything you can. What does the physical evidence suggest about the historical development and social character of the area? What questions does it raise that you would like to have answered through historical research?” Why so many high-rise apartment buildings along Lake Shore Drive? one student wonders. How did Harper Avenue between 57th and 59th Streets acquire its liberal, close-knit aura? another asks. An answer to the first question might have to do with evolving lifestyles or improved transportation, Conzen suggests, while an answer to the second might begin with Harper Avenue’s own beginnings as a quasi-resort community on the city’s edge. Time runs out before the observations do, but the point is made: behind every block is a backstory—and a multitude of routes to finding the plot.—M.R.Y. |

|

Contact

|