|

|

| Myth Information Are Fermi’s notes radioactive? Do Pierce’s rooms violate U.S. prison codes? Does anyone leave campus with a 4.0? Here’s the truth about Chicago’s most popular legends.

She was the daughter of a wealthy family, sent to Chicago to pluck the fresh fruits of the young University. Yet Ida Noyes was unhappy, struggling to make friends. She tried, campus lore has it, to join a sorority, but was rejected by every one. Some say Ida, solitary and despondent, cast herself into Lake Michigan. No, others argue, it was worse than that: Ida’s imploring finally swayed one sorority to admit her—after the requisite hazing. The cruel sisters rowed her some distance out on Lake Michigan, then hurled her into the cold, tossing waters. “Swim for your life, Ida! Swim, and we shall admit you!” Ida, desperate for companionship and her peers’ approval, tried to stay afloat, though she’d never learned to swim. But it was not to be. Her delicate limbs and the cumbersome women’s fashions of the time quickly soaked and grew heavy. As the sisters rowed on, she foundered. They cried out to her, but Ida insisted she could reach the shore. She did not remain long above the surface. The sisters rowed back and reached under the water to grasp her, but Ida already had been swallowed by Lake Michigan’s depths. Her father’s reaction was measured; he knew the ways of the world. So he exacted a philanthropist’s revenge, donating a building, the finest yet constructed on campus—on two conditions: Chicago must require all students to pass a swimming test to graduate, and never, never was a sorority to possess its own residence on campus. The University has abided by the two regulations ever since. Alas, this charming piece of the macabre is completely false. Ida Elizabeth Smith attended Iowa State College, where she met the man she later married, inventor and industrialist La Verne Noyes. In 1879 the couple moved to Chicago. Ida enrolled in the School of the Art Institute and soon became attached to the booming metropolis. After traveling in Europe and along North America’s Pacific coast she returned to Chicago, joining numerous women’s clubs and artistic societies. She died December 5, 1912, at 59. Six months later her husband, in memory of Ida and her contributions to Chicago’s cultural life, announced he would donate a building to the city’s intellectual capstone. With $300,000 from La Verne Noyes, the University built “a women’s social center and gymnasium.” The hall’s cornerstone was laid April 17, 1915. Noyes’s donation exacted no demands on University policy. The more exciting tale comes from various reports by alumni and current students. Molly Proue, AB’02, heard that the College’s swimming requirement was instituted because Ida Noyes had drowned in a lake. Claire Toth, AB’80, JD’82, was told that Ida was rejected by every campus sorority and killed herself; her rich father donated the hall on the condition that the University never allow sororities. Vera Biller, AB’04, synthesized the two stories she heard from older sorority sisters; now it was Ida’s Lake Michigan hazing that killed her. Connections between drowned students and swimming requirements permeate higher education. Swarthmore College has an almost identical myth about the wealthy parents of a drowned female student making a donation in exchange for mandatory swim tests. A similar story surrounds Harvard’s Widener Library, named after a student who died on the Titanic. These and other accounts appear in the online Urban Legends Reference Pages (www.snopes.com). But if the Ida Noyes tale is false, why don’t U of C sororities own houses? Until the 1985 arrival of Alpha Omicron Pi, Chicago had no sororities as such, only women’s social clubs that did not cohabit. Many universities that lack sorority houses, including Chicago, Denison in Ohio, and Tulane in New Orleans, have spread the myth that old brothel laws prohibit more than six or eight women from living together. “There is no such law,” says Dorothea Hunter, AB’04, last year’s vice president of recruitment for the University’s Panhellenic Council. The reason none of the U of C’s three sororities own houses is simply economic, says assistant director of student activities Lori Hurvitz. “Property is just too expensive. I know the chapters would like to purchase houses, but they’re too small to get the capital they would need.” As for the swimming requirement—College students must take both a general physical-education test and a swimming test—director of physical education and athletics Tom Weingartner does not know when or why the University adopted the policy. The Urban Legends Reference Pages explain, “Requiring graduates to pass a swim test seems to have originated about the time of World War I, as part of a Red Cross effort to teach swimming skills to all Americans.” Though the University’s first swimming pool was part of Ida Noyes Hall, required swimming courses did not appear in the undergraduate course catalog until 1954–55.

Abby Chua, AB’99, and Darcy Lewis, AB’02, recall the yarn that some sections of the Regenstein Library basement are radioactive because they’re near the site of the first self-sustained nuclear chain reaction, conducted December 2, 1942, by Enrico Fermi. Fermi’s notes, in the Reg’s possession, also are radioactive, the tale continues—held in a lead box and inaccessible. The Reg is not radioactive, assures Jay Satterfield, former head of reader services at the Special Collections Research Center, where Fermi’s notes are indeed available for viewing. Thirty-five linear feet of lectures, papers, correspondence, and course materials are held in 65 boxes (made of cardboard, not lead) in Special Collections’ vaults. The closest the Reg comes to radioactive substances is Susan kae Grant’s concept-art book, Radio-active Substances. Though not radioactive, the book, named after Marie Curie’s 1904 study, comes in a lead box and consists of paper scrolls tucked in glass test tubes. The birds Hyde Park dwellers can’t fail to notice

unexpected urban wildlife—specifically, the bright green birds

that pop out of huge, bulbous nests and fill the air with shrill

chattering. The infamous monk parakeets’ invulnerability to

Chicago’s bitter winters has made them the stuff of legend,

though their survival is not such a mystery. Myiopsitta monachus

is well acclimated to the cold, originating in chilly, mountainous

regions of Brazil and Argentina, and the feral birds’ insulated

nests easily withstand North American temperatures. Nor are they

unique to Hyde Park; their U.S. invasion began in the 1960s, when

they were a popular exotic pet. Though brought here as trendy companions, in Argentina the parakeets are considered major agricultural pests. The U.S. Department of Agriculture, deeming the birds likewise, planned to eradicate the Hyde Park colonies in 1988. One of the largest nests, in a park at 53rd Street and Hyde Park Boulevard, sat across from the late Mayor Harold Washington’s apartment. Washington, who died in 1987, reportedly had liked the creatures. Local residents formed the Harold Washington Memorial Parrot Defense Fund, successfully thwarting the feds with protests and a threatened lawsuit. A police car even parked under the nest some nights to protect it. This past June the birds suffered a natural disaster: the huge Washington Park ash tree that was home to about 50 parakeets collapsed, possibly because of the tree’s size and a hole in its center. Chicago Animal Control workers rebuilt the nests, moving them to a tree further north in the park. Buried in the Rock

One campus legend with a firm footing in reality holds that the University’s past presidents are buried in Rockefeller Memorial Chapel. Indeed, on a wall beyond Rockefeller’s reredos—the ornamental screen behind the altar—aging metal plaques mark the tombs of seven of Chicago’s nine dead presidents: William Rainey Harper and his wife Ella; Harry Pratt Judson and his wife Rebecca; Ernest DeWitt Burton, his wife Frances, and their daughter Margaret; Lawrence Alphaeus Kimpton, his first wife Marcia, and his second wife Mary; George Wells Beadle and his wife Muriel; Edward Hirsch Levi, PhB’32, JD’35, and his wife Kate; and John Todd Wilson and his wife Ann. Robert Maynard Hutchins, who served between Burton and Kimpton, is buried in Santa Barbara, where he died in 1977. Max Mason, president in the mid-1920s, died in Claremont, California, in 1961. Banned landmarks Campuses become protective of certain sacred sites—places where one must not tread lest terrible consequences follow. The most famous such spot at Chicago is the seal in Mitchell Tower (the bronze floorplate in the Reynolds Club lobby bearing the University’s crest). A 1919 Maroon warns the unsuspecting first-year that if an upperclassman sees him stepping on the seal, he may be tossed in Botany Pond. While today’s students no longer threaten to dunk underclassmen for walking over a metal plate, they are familiar with a legend that stepping on the seal dooms the violator to extra undergraduate years. Debunking the myth, alumni such as Daniel Jacobs, AB’93, Brian Ogilvie, AB’90, AM’92, PhD’97, Karl Davis, AB’03, and Darcy Lynn Lewis, AB’02, all boast of fearlessly jumping on the seal yet still graduating in four years. A similar prohibition held for sitting on the C-Bench near Cobb Hall, where only lettermen and their girlfriends were allowed to recline. The rule waned in the ’60s, and the myth became muddled; Barbara Greenstein, AB’71, heard that no virgins ever sat on the bench. (Virginal myths abound on college campuses. “Every school wants to think of itself as ‘the party school to end all party schools,’” say the Urban Legends Reference Pages, “and legends about virgin-inspired statues or fixtures play to this image.”) Another landmark that fascinates the student body is Virginio Ferrari’s sculpture Dialogo outside Pick Hall. Locals say that every May 1—International Workers’ Day—the four-piece bronze sculpture casts a shadow that unmistakably resembles the Soviet hammer and sickle. Alas, this past May 1 was overcast, so the tale couldn’t be confirmed firsthand. But some administrators, such as Rockefeller’s assistant to the dean for external affairs Lorraine Brochu, swear to the story’s truth. The mystery is whether the shadow was intentional and whether the date is significant. Ferrari, the University’s artist-in-residence when Pick was built in 1971, made no Communist references in his work. He described his intentions in the June/71 Magazine: “What I want to call to mind in this sculpture is the four corners of the world. ... They rise up slowly and become soft and delicate; two of the forms almost touch in the center in a caressing manner. The third, almost a circle, hovers over the two, to suggest protection and security for the life of tomorrow. The fourth form represents a big wave, symbolic of the water that surrounds and unites all of the continents.” The Soviet shadow, it seems, is merely a coincidence. The marriage myth Chicago students say the University is practically void of a dating scene, but both students and alumni spread the misinformation that Chicago graduates marry each other at wondrous rates. A Maroon story on “U of C traditions” in the 2003 orientation issue, for example, noted that “almost 50 percent of U of C students take the plunge with a fellow classmate.” Christine Love, outgoing Alumni Association executive director, once overheard a group of young alumni at Bonjour Bakery placing the number as high as 80 percent. “I couldn’t stop myself,” Love says. She dutifully introduced herself and set the record straight: according to the University’s directory, only about 10 percent of Chicago alumni exchange vows. Love reports, “They were shocked,” as may be some Magazine readers.

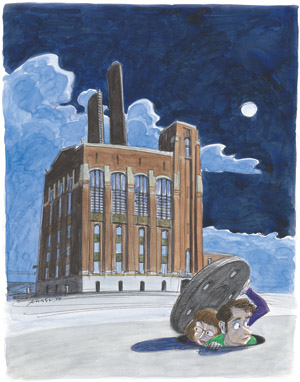

Underworld dreams Legend tells of a dank, labyrinthine network

of tunnels running underneath the Midway, linking the Law School

and Burton-Judson to the campus’s north side. It’s true.

Tunnels containing steam pipes connect the quads to the University

steam plant at 61st and Blackstone, extending west to the Hospitals

and north to Pierce Hall at 55th and University. Some alumni had heard that the tunnels were closed in the 1960s because a female student was murdered there. “I have no knowledge of any murders,” DeSoto says, “nor have we ever found any bodies.” The lack of newspaper stories about steam-tunnel murders on the Midway further suggests that this tale is simply another urban legend. Ways to make the grade Sharon Greene, AB’00, recalls hearing that only a handful of the University’s undergraduates ever leave with a 4.0 GPA. Hard-pressed students—and alumni wary of grade inflation—may be comforted to know that the story is generally true. Indeed, 4.0 grads are rare, says Associate Registrar Andy Hannah. This year the highest GPA was a 3.98; in 2003 only two students were graduated with the coveted 4.0. Other campus myths reflect the dark imagination of the undergraduate mind. Many schools hold the notion that the roommate of a student who dies (the story often specifies suicide as the cause) will receive straight A’s for that term. The tale is so widespread that it served as the premise for MTV Films’ 1998 release Dead Man on Campus. While the University offers support to bereaved students, says Dean of Students in the College Susan Art, AM’74, that support doesn’t extend to automatic A’s. “Grades are earned,” says Art, “not given as gifts.” Charles Hoffman, AB’01, “heard from numerous sources that the undergraduate break in the middle of winter quarter—a Monday in early February known colloquially as “Suicide Prevention Day”—“was scheduled on the day statistically shown to have the highest suicide rate.” Wrong again. Most U.S. suicides occur in the spring, according to the American Association of Suicidology. And anyway, Art says, “it is foolish to think that a day off from classes could accomplish anything in this regard.”

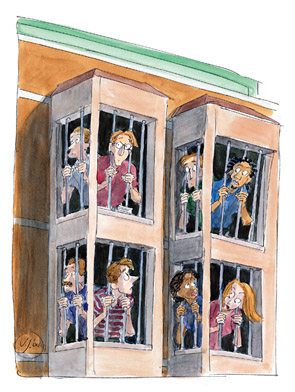

Fretting in Pierce Hall’s minuscule rooms, undergraduates have long fixated on the building’s distinctive bay windows. David Billmire, AB’03, a Pierce resident his first year, relished the legend that the building’s original design had wall-set windows; the protruding bay windows were a last-minute change after the architects and the House System realized that without the added inches the rooms would be so small they’d violate U.S. prison codes. The dimensions of Pierce’s doubles, according to University architect Curt Heuring, are 168 square feet, small compared to other dorm doubles—290 square feet at Burton-Judson and 270 square feet at Max Palevsky. Pierce’s 1957 design, by architects Harry Weese Associates, planned 171-square-foot doubles, citing comparable rooms at the University of Illinois (165 square feet), Iowa State (168 square feet), and Northwestern (180 square feet). The designs likely faced no legal problems; the American Correctional Association’s recommended standard cell size is at least 35 square feet of “unencumbered” space—free of furnishings or fixtures—per prisoner. An inmate confined for more than 10 hours per day should have at least 80 unencumbered square feet. Room sizes were not even an issue while Pierce was on the drawing board—where bay windows were a part of the original design—although architect Eero Saarinen, at work on a University master plan, had qualms about the rooms’ shape. In an October 7, 1957, letter to Weese, he noted: “I have some misgivings about the proportions of your blocks. It seems to me they are very dumpy-looking. They are neither vertical nor horizontal. I think you ought to study this model more.” By March 1958 Saarinen had reversed course, praising Weese’s “accentuation of the vertical by use of bay windows.” And Pierce’s first residents, according to surveys taken in 1960, were unconcerned about aesthetics and room size, complaining instead about poor acoustics and dim lighting. Maybe a building has to age before its features appear strange to new students and the lore starts flowing. A Macalester College legend, for instance, holds that unappealing dorms built in the turbulent ’60s were designed with narrow windows to make them riot-proof—a false claim also made about Pierce. Such tales beg the question: what might students say about Max Palevsky Commons in 40 years? |

|

phone: 773/702-2163 | fax: 773/702-8836 | uchicago-magazine@uchicago.edu

The

lamentable tragedy of Ida Noyes

The

lamentable tragedy of Ida Noyes Aglow

in the stacks

Aglow

in the stacks According

to Columbia University’s Introduced Species Summary Project,

wild colonies quickly spread across the country after a crate broke

open at New York’s JFK International Airport in 1967, an incident

that likely inspired a similar myth about O’Hare.

According

to Columbia University’s Introduced Species Summary Project,

wild colonies quickly spread across the country after a crate broke

open at New York’s JFK International Airport in 1967, an incident

that likely inspired a similar myth about O’Hare.

The

Magazine’s “Chicagophile” cartoonist

Jessica Abel, AB’91, toured the underground system with steam

plant assistant manager Mike DeSoto and recorded her journey in

the April/99 issue, in which DeSoto described finding graffiti,

beer bottles, and even students inside the tunnels. Since then,

DeSoto says, the University has secured the entranceways, adding

gates and welded bars. “There was a time when it was very

common to see someone wandering in the tunnels in the middle of

the night,” he says. “We’d call security, and

they’d take the students back to their dorms. But to my knowledge

there have been no new student intruders in quite some time.”

The

Magazine’s “Chicagophile” cartoonist

Jessica Abel, AB’91, toured the underground system with steam

plant assistant manager Mike DeSoto and recorded her journey in

the April/99 issue, in which DeSoto described finding graffiti,

beer bottles, and even students inside the tunnels. Since then,

DeSoto says, the University has secured the entranceways, adding

gates and welded bars. “There was a time when it was very

common to see someone wandering in the tunnels in the middle of

the night,” he says. “We’d call security, and

they’d take the students back to their dorms. But to my knowledge

there have been no new student intruders in quite some time.”

Another

myth pierced

Another

myth pierced