|

||

|

Features ::

Traditional economics holds that humans, as rational beings, make choices to maximize their welfare. Chicago’s Richard Thaler argues that policy makers—including those working on President Bush’s plan to partially privatize Social Security—would do well to remember that rationality has its bounds.

“There’s no reason to think that

markets always drive people to

what’s good for them.”

—Richard Thaler

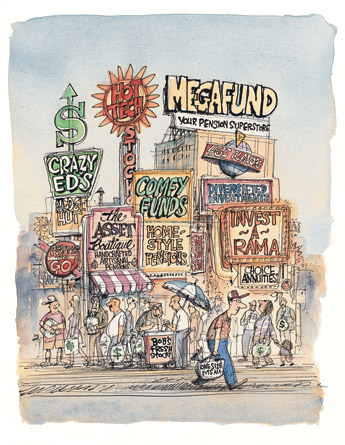

A few weeks later Sweden’s 4.4 million working-age adults received blue packets in the mail. They had four weeks to select an investment portfolio and return the form in a postage-paid envelope. They could, a personalized letter explained, invest 2.5 percent of their annual pay in the new funds, while the rest of the 18.5 percent of their annual income contributed to social security would remain in the traditional pension system. A “What to Do” brochure described the procedure in four steps. A catalog gave an “easy to understand” list of 456 funds from which investors could pick. Although a default fund offered a low-cost, well-diversified allocation of assets, the overall message was clear: Swedes should take charge of their own financial futures.

So began what Richard Thaler, the Robert P. Gwinn distinguished service professor of behavioral science, economics, and finance in the Graduate School of Business, considers a massive field experiment into what could happen if every Lars, Olaf, and Kristina chose how to manage their social-security funds. In the American Economics Association’s May 2004 AEA Papers and Proceedings Thaler and GSB doctoral candidate Henrik Cronqvist analyzed early results from Sweden’s Pension Premium Authority (PPM). Moving beyond Sweden, the research offers timely insights as President George W. Bush renews his efforts to partially privatize Social Security. While most economic writings on social-security design focus on macroeconomic aspects such as funding, Thaler and Cronqvist’s approach is microeconomic. Analyzing the particulars of PPM’s set-up and how those details influenced the users’ behavior, they found some “undesirable” results: Swedes who actively invested their own pensions chose more expensive, less diversified funds than those picked by the default plan.

The paper is a classic example of the growing literature in behavioral economics, a school of thought that, under Thaler’s leadership over the past 30 years, has been seeping into economics departments and academic journals. Traditional economics teaches that humans are rational actors who make decisions in ways that maximize their well-being. Behavioral economics, meanwhile, relies on cognitive-psychology research to relax those assumptions, teaching instead that humans have “bounded rationality”—a term coined in 1957 by economics Nobelist Herbert A. Simon, AB’36, PhD’43—and so make biased decisions that sometimes run counter to their best interests. Despite a spate of recent media coverage depicting two hard-headed camps the twain of which shall never meet, the fact is that after three decades behavioral economics has made clear headway into the field’s mainstream. These days, says Thaler during a November conversation in his office overlooking the Midway Plaisance, “most economists recognize that some of the people are not fully rational some of the time, and some of the time that matters.” What most traditionalists are not willing to grant is that bounded rationality carries much weight in a market setting; they believe rational actors cancel out the irrational ones. Behavioralists disagree, arguing that bounded rationality does indeed bump the market’s invisible hand.

To prove their point, Thaler and like-minded colleagues have set their sights on using behavioral findings to influence both U.S. Social Security policy and the employer-sponsored private systems by which U.S. workers save for retirement, such as 401(k)s.

Back in Sweden, PPM was conceived on the conventional economic belief that, given lots of information, consumers can better weigh their options and as a result make better decisions; it’s a laissez-faire economist’s—and libertarian’s—dream come true. Because unfettered competition, traditionalists believe, drives down costs and eliminates inferior products, any fund meeting certain standards could enter the market and, with the exception of the default fund, set its own fees and advertise to attract participants’ money. “The combination of free entry, unfettered competition, and free choice seems hard to quarrel with,” Thaler and Cronqvist write. But they raise a standard behavioralist’s caution: “However, if participants are not well-informed or highly motivated, then maximizing choice may not lead to the best possible outcome.”

The PPM’s outcomes illustrate their point. True to the ads’ urging, when those millions of selection forms flooded back into the agency’s offices, fully two-thirds of participants had eschewed the default fund and selected their own portfolio. (Women, interestingly, were more likely to actively choose than men, perhaps because, Thaler suggests, women may be less likely to lose mail-in forms.) In mid-February 2001 the Wall Street Journal reported that, although analysts had expected the largest Swedish banks to pick up most new private pension accounts, many Swedes chose smaller providers and even foreign companies. Free-market thinkers took this as a good sign; the Cato Institute’s Social Security This Week newsletter opined, “It seems that given a free choice and plenty of information, Swedish investors are hungry for new alternatives. ... The PPM has already fostered a new culture of investment for Swedes, long accustomed to cradle-to-grave protections through the welfare state.” Carl Bernadotte, head of CB Asset Management in Stockholm, told the WSJ, “Everybody in Sweden is talking about choosing their PPM funds. It’s incredible. Even if it is only a small 2,000 euro investment and they have thousands invested elsewhere, they go to dinner parties and lunches and talk about which funds to buy in the PPM. It’s changed the way we talk about investing in Sweden.”

For Thaler and Cronqvist, talk is one thing, results another. How did Swedes’ selections fare? The original default portfolio was allocated mainly toward non-Swedish stocks (65 percent). Another 17 percent went into Swedish stocks, 10 percent into inflation-indexed bonds, 4 percent into hedge funds, and 4 percent private equity. More than half of the default’s funds were indexed, meaning they represented a broad cross-section of the stock market and were managed passively (the whole “buy and hold” idea); as a result the fund’s management fees were low. Thaler and Cronqvist’s only quibble with the default fund is that it leaned too heavily toward Swedish firms’ stocks. But in the three years since the program began, they note, the default fund has received the highest five-star ranking from the fund-rating service Morningstar. Good thing the default was intelligently designed, Thaler and Cronqvist say, because given human nature and a tendency to stick with the status quo or procrastinate, defaults attract a disproportionate market share; in Sweden the default received the highest market share—33 percent—of any fund.

The

other two-thirds of participants’ money was scattered across the 456-fund

list, making it difficult to compare the outcomes. So Thaler and Cronqvist

calculated the mean aggregate portfolio of Swedes who chose their own funds.

Despite initial enthusiastic reports, that portfolio, they found, leaned

even more heavily toward stocks than the default fund—96.2 percent,

of which 48.2 percent were Swedish stocks. Only 4.1 percent of the funds

were indexed, and as a result participants paid higher fees. The fund that

attracted the largest market share, aside from the default, was Robur Aktiefond

Contura, specializing in Swedish technology and health-care stocks, whose

value soared 534.2 percent over the five years preceding the PPM launch.

Three years later, however, it had lost 69.5 percent of its value. Overall

the mean aggregate portfolio was down 39.6 percent after three years. The

default fund, on the other hand, was down significantly less, 29.9 percent—not

too terrible given that markets were falling worldwide.

The

other two-thirds of participants’ money was scattered across the 456-fund

list, making it difficult to compare the outcomes. So Thaler and Cronqvist

calculated the mean aggregate portfolio of Swedes who chose their own funds.

Despite initial enthusiastic reports, that portfolio, they found, leaned

even more heavily toward stocks than the default fund—96.2 percent,

of which 48.2 percent were Swedish stocks. Only 4.1 percent of the funds

were indexed, and as a result participants paid higher fees. The fund that

attracted the largest market share, aside from the default, was Robur Aktiefond

Contura, specializing in Swedish technology and health-care stocks, whose

value soared 534.2 percent over the five years preceding the PPM launch.

Three years later, however, it had lost 69.5 percent of its value. Overall

the mean aggregate portfolio was down 39.6 percent after three years. The

default fund, on the other hand, was down significantly less, 29.9 percent—not

too terrible given that markets were falling worldwide.

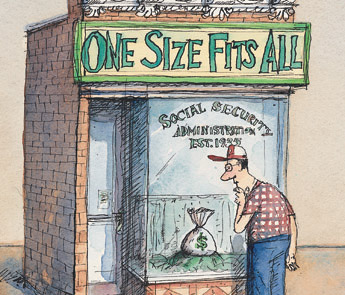

Although Thaler and Cronqvist acknowledge that “three years of returns does not prove anything,” they believe the United States can draw several lessons from Sweden’s experience. First, a default fund must be devised carefully, because human nature dictates a large portion of investors’ money will go there. With a U.S. economy 30 times the size of Sweden’s, free-market entry for funds could result in thousands of choices, paralyzing the average consumer. Instead, the authors recommend offering a small number of funds, perhaps three, investing in index funds and bonds, with varying levels of risk. The funds would be managed by private firms subject to competitive bidding.

President Bush’s proposal for Social Security reform, a 256-page document titled “Strengthening Social Security and Creating Personal Wealth for All Americans” (available for downloading at csss.gov) offers evidence of behavioral economics’ move into the mainstream. Though no behavioralists sit on the bipartisan commission that wrote the report, its plan, Thaler admits, “is not much different from what we would propose.” The document outlines three possible models through which 2 to 4 percent of a worker’s wages would be invested in private accounts. Each model includes a “standard fund,” akin to the Swedish default. A two-tier system allows initial contributions, say up to $5,000, to be invested in a limited number of funds, between three and five; once the first-tier threshold is reached, a still-to-be-determined number of second-tier funds will be available for investment. Fund managers must meet certain standards and compete to be included in the second tier. A governing board would be created to provide workers with “informative advice, and to implement reasonable changes in either tier that it believes is in the best interest of workers and retirees.”

But even the best-intentioned planning, says Thaler, can be thwarted by widespread bounded rationality. While traditionalists argue that markets eliminate such effects, the Swedish case, he believes, shows otherwise. “‘Markets will take care of it?’” he echoes, voice rising in disbelief. “The Swedish case is the market. A high-tech fund that’s gone down 69 percent. That’s the market. There’s no reason to think that markets always drive people to what’s good for them. Markets also drive people to what’s good for the people selling.”

THALER IS IN HIS LATE 50S, has wavy silver hair, and dresses casually in dark chinos and black loafers, button-down shirt open at the collar. Of late his name has repeatedly appeared on most-likely lists for the economics Nobel. He is given to quoting long-gone Chicago economists, particularly those who espoused theories other than the neoclassical maxims of acting rationally and maximizing well-being. His point is that behavioral economics’ roots go far deeper than the mid-1970s, when his doctoral work at the University of Rochester on the value of human life convinced him that something was missing from the standard theories. Among the Chicagoans Thaler quotes is John Maurice Clark, who taught at the U of C from 1915 to 1926. “The economist may attempt to ignore psychology, but it is sheer impossibility for him to ignore human nature,” Clark wrote in a 1918 Journal of Political Economy. “If the economist borrows his conception of man from the psychologist, his constructive work may have some chance of remaining purely economic in character. But if he does not, he will not thereby avoid psychology. Rather, he will force himself to make his own, and it will be bad psychology.” Quips Thaler, “I’m just trying to borrow good psychology and not invent my own.”

Clark was writing as psychology was emerging as a distinct field, not yet considered scientific. At the same time, as Caltech behavioralist Colin Camerer, MBA’79, PhD’81, notes in a 2003 essay, “economists hoped their discipline could be like a natural science. ... Their distaste for the psychology of their period...led to a movement to expunge the psychology from economics.” But economics and psychology once had been inextricably intertwined; Camerer cites Adam Smith’s lesser-known book The Theory of Moral Sentiments as “bursting with insights about human psychology, many of which presage current developments in behavioral economics.” So, in a sense, behavioral economics’ recent groundswell is actually, according to Camerer, a “return to the roots of neoclassical economics after a century-long detour.”

The difference now is that psychology has long since come into its own as a scientific discipline adept at systematic research. Cognitive psychology’s two most influential axioms for economics come from Stanford psychologist Amos Tversky, who died in 1996, and his longtime collaborator, Princeton psychologist Daniel Kahneman, a 2002 economics laureate. Both findings are examples of Herbert Simon’s bounded rationality. During the 1970s Tversky and Kahneman studied how people make decisions under uncertainty. When faced with lots of information they aren’t sure how to process, most people, the psychologists found, come up with rules of thumb to help them proceed. Although evolutionarily useful, these “heuristics,” as the cognitive shortcuts are called, can lead to biases that, in turn, can lead to faulty decisions. In Sweden, for example, many active choosers fell prey to an “extrapolation bias”: influenced by hot-shot tech funds’ recent returns, they chose the riskier investments. Meanwhile, victims of the “familiarity bias” stuck disproportionately with Swedish stocks, ultimately an arbitrary decision. Advertising by the various funds merely exacerbated the biases, as Cronqvist reports in his doctoral dissertation.

Tversky and Kahneman also developed “prospect theory.” Another example of bounded rationality, it contradicts the standard economic teaching that, as Chicago professor and 1992 Nobelist Gary Becker, SM’53, PhD’55, wrote in his 1976 The Economic Approach to Human Behavior, “[A]ll human behavior can be viewed as involving participants who maximize their utility from a stable set of preferences and accumulate an optimal amount of information and other inputs in a variety of markets.” In other words, Becker says, people know what they want from the start, and they update their preferences as new information comes in. Tversky and Kahneman’s research on heuristics, however, demonstrates that people do not always start with a stable set of preferences; particularly in unfamiliar situations, they use rules of thumb to cobble their preferences together as they go.

While rational-choice theory argues that people “maximize utility,” making decisions in absolute terms, prospect theory argues that people make decisions according to how they perceive their current state, or wealth, will change. And, prospect theory goes on, like moving or standing objects, people are prone to inertia. That’s one reason why default options are so popular. It’s also why, once a decision is made, such as allocating savings into a certain mix of funds, the chooser tends to stick with it even when circumstances change, such as a high-tech stock bubble bursting. The theory also postulates that most people find losses more agonizing than gains pleasurable. In 1998 Thaler and UCLA’s Shlomo Benartzi drew upon prospect theory and other psychological insights to design a program called Save More Tomorrow (SMarT), in which participants at a mid-sized manufacturing firm committed in advance to allocating a portion of their future salary increases toward retirement savings. The results were dramatic. The average saving rates rose from 3.5 percent to 11.6 percent over 28 months. With savings tied to pay increases, participants never saw their paychecks decrease, and thus their aversion to loss did not override a wise decision.

Another prospect-theory hypothesis is that people make decisions based on whether they view each option as a gain or a loss. Thus the way in which choices are worded becomes incredibly important. In Sweden the initial PPM advertising campaign, with its emphasis on active choice, established a powerful frame within which 67 percent of participants decided it was in their best interest to select their own portfolio. Now that the ad blitz has ended, new enrollees are far more likely to select the default fund. In fact, only 8.4 percent of new enrollees pick their own portfolios, from an offering of some 600 funds. The massive drop-off in active enrollment has made Thaler and Cronqvist wonder, “Is it worth spending the extra money to offer choices?” When partially privatizing U.S. Social Security, they ask, why bother to offer even three funds? Why not offer only one well-designed, low-fee index fund?

“It doesn’t matter what you or I do.

It’s how the whole group behaves.”

—Gary Becker, SM’53, PhD’55

HERE IS WHERE BEHAVIORAL ECONOMICS OVERSTEPS its bounds, according to critics who maintain the rational-choice, maximizing-utility point of view—by far the majority among the field’s academics and policy makers. Moving forward with paternalistic policy proposals based on behavioral economics, such as limiting choice in Social Security reform, would be, in traditionalists’ view, premature at best. They argue that, although individuals can make poor choices, in a market context rationality cancels out individual psychology.

That’s certainly Gary Becker’s view. “While I believe there’s value in some areas of psychology, the focus is different,” he says between telephone calls and back-to-back meetings this past November. The dry-erase board on his office wall is awash in scribbled mathematical equations, broken up by one word: always. “We’re interested in how groups respond.”

Having spent much of his career studying human behavior within social networks, Becker, who holds appointments in sociology, economics, and the GSB, is convinced that psychology’s impact on economics is limited. “If there’s a tax on wages, it doesn’t matter what you or I do, but how the whole group reacts.” Division of labor, he continues, “strongly attenuates if not eliminates any effects” caused by bounded rationality. In other words, “it doesn’t matter if 90 percent of people can’t do the complex analysis required to calculate probabilities. The 10 percent of people who can will end up in the jobs where it’s required”—such as dealing blackjack, Becker’s example, or managing mutual funds.

But in the Swedish situation, Thaler points out, citizens picked their own portfolios, whether or not they were good at it. “Maybe Gary Becker sometimes confuses behavioral economics with psychology,” says Thaler. “Because behavioral economists think about markets all the time.”

At Becker’s Rational Choice Workshop last spring, Harvard’s Edward Glaeser, PhD’92, took up the question of group psychology in his paper “Psychology and the Market.” “The great achievement of economics is understanding aggregation,” he writes. “Our discipline has always been about the wealth of nations, not individuals.” During a November phone interview Glaeser comments that economists like Thaler are “moving in the right direction. There’s a large and growing behavioral finance literature that’s convincing. I can’t think of a main thrust that I disagree with.” Most differences of opinion, he says, can be attributed to the long, slow, creaking way in which new ideas are hammered out within a discipline. Behavioralists, he believes, simply haven’t gotten to the point yet where they can fully explain what happens in a market. “Much of the early work has focused on changing the core of economics with work on individuals. It’s hard to read the bulk of the research and not think it specializes more on individuals,” he reflects. “But that’s a tactical decision, not a strategy.”

Behavioralists admit such a shortcoming. In Camerer’s history, he describes the time-tested recipe for behavioral-economics research: “First, identify normative assumptions or models that are ubiquitously used by economists. ... Second, identify anomalies—i.e., demonstrate clear violations of the assumption or model, and painstakingly rule out alternative explanations (such as subjects’ confusion or transaction costs). And third, use the anomalies as inspiration to create alternative theories….” A fourth step is to construct new economic models and test them. This crucial final step, he writes, has only lately been attempted. For example, there are now behavioral models that demonstrate the bounds of human self-control; other models reveal the limits on humans’ ability to make “intertemporal choices,” that is, people have a cloudy understanding of how their choices now will play out in the future. Thaler sounds a similar tone. “Progress has been made, there is lots to do,” he writes in his 1991 book Quasi Rational Economics. “There is more than enough work to go around.”

The call for comrades has gone out—and been heeded—with financial help from Eric Wanner, a cognitive psychologist by training who serves as president of the New York–based Russell Sage Foundation and whom Thaler describes as the “angel” of behavioral economics. Since 1984, when Wanner made the first grant toward furthering research exchange between psychology and economics—funding a yearlong sabbatical for Thaler to work with psychologist Kahneman, then at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver—the Russell Sage Foundation has provided $5.4 million toward behavioral economics. “A little money at the right time in the right place can go a long way,” Wanner says, underwriting 140 small research grants, a book series, and since 1994 a biannual two-week-long summer institute for graduate students, known informally as the behavioral economics summer camp. Wanner describes the institute as a “greenhouse” for the field. “This stuff is still not taught in the system,” he says. Although most economics departments now have someone doing “behaviorally flavored” work, he believes it wouldn’t be so without the institute. Indeed, most current prominent behavioralists—including Harvard’s David Laibson and Berkeley’s Matthew Rabin, who organized the 2004 institute—have attended the camp.

Despite the work to be done, Thaler believes it’s high time to put the behavioral findings into action, partly because he sees no distinction between economics and behavioral economics. Here he quotes Herbert Simon in the New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics. Simon argued that “the phrase ‘behavioral economics’ appears to be a pleonasm,” or redundancy: “What non-behavioral economics can we contrast it with? The answer to this question is found in the specific assumptions about human behavior that are made in neoclassical economic theory.”

Thaler’s paper with Cronqvist underscores his belief that psychology affects the market in ways neoclassical theory fails to predict. The paper is also an example of what Thaler calls “libertarian paternalism,” a broad view of policy making that he is mapping out with Cass Sunstein, the Karl N. Llewellyn distinguished service professor of jurisprudence in the Law School, political science, and the College. Their premise is simple: because the average person’s decision making is hampered by bounded rationality, it behooves policy makers to create programs that make it easier for people to maximize their well-being.

They can, for instance, offer attractive, carefully framed default options and not inadvertently discourage people from selecting them by overemphasizing the benefits of making their own choice. Or set up a plan in which people can more easily increase their employer-sponsored retirement savings. Thaler and Benartzi’s SMarT plan, launched in 1998, is going strong. Since the initial experiment, the 401(k) plan administrator Vanguard now offers SMarT to 200 corporate clients, with more than 400,000 employees eligible to join. Other retirement-plan administrators, including T. Rowe Price and Fidelity, also plan to roll out the program. Thaler predicts that in five years SMarT will have 1 million participants.

What does a rational-choice economist like Glaeser say to SMarT? “I have no strongly averse reaction,” he comments. But libertarian paternalism is, he says, a slippery slope. “It’s when we talk about government having a benign paternal twist that I tend to shudder.” Recognizing humans’ “sensitivity to stimuli” such as frames and biases should increase sensitivity to government intervention. SmarT is “a benign program, but we shouldn’t go farther down the slope.”

Such comments make Thaler throw up his hands. “It is precisely because humans are so sensitive to stimuli that we must be careful in designing programs. Libertarian paternalism does not imply a greater role for government, and because it is libertarian, we insist on retaining free choice. But once you know that every design element has the potential to influence choice, then you either close your eyes and hope for the best, or you take what you know and design programs that are helpful.” Thaler is particularly frustrated by the argument that accepting bounded rationality implies that bureaucrats should be trusted even less and the market even more. “It’s not the point,” he says. “The point is, what can boundedly rational but well-motivated planners—a category in which I include bureaucrats, CEOs, school principals, mothers—what can they do to improve the decision making of people over whom they have influence, without restricting anyone’s freedom?”

The trick, he says, is giving people the best shot to make a good decision. “Our whole agenda is to create forgiving environments. The Swedish social security laissez-faire attempt taught us some useful lessons. They correctly paid a lot of attention to devising a good default fund, but it was probably a mistake to discourage its selection.” In fact, in a case where most participants are not well-informed, he says, “it might be better to lean the other way and say something like, ‘Experts have picked a default fund, and if you are not sure what to choose, it might be a good choice for you.’ That suggestion doesn’t make me a communist, totalitarian guy.” It makes him a behavioral economist.