|

||

|

Peer Review ::

Dramaturge Rachel Shteir reveals layers of cultural meaning behind the risqué art.

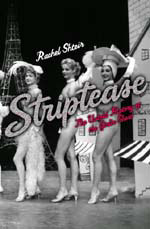

Rachel Shteir, AB’87, didn’t want to be a “straight academic,” as she puts it. Mission accomplished. Shteir, associate professor and head of DePaul University’s dramaturgy and dramatic criticism program, has published Striptease: The Untold History of the Girlie Show (Oxford University Press, 2004). The book’s topic, as its numerous reviews demonstrate, appeals to an audience beyond the Ivory Tower. Sexy, marketable characters—“shimmy girls,” “cootch dancers,” and “tit serenaders”—cavort inside its pages. But Shteir also raises scholarly, feminist questions about the art form.

Don’t get the wrong idea. She isn’t interested in painting striptease as either liberating or degrading. That’s been done. Instead she approaches the popular entertainment as a slice of Americana, chronicling its heyday from the Jazz Age to the Sexual Revolution. “It’s not enough to talk about how these women were exploited or empowered,” she explains this winter from her small Lincoln Park office, a former nun’s dormitory where theater books fight for floor space. “It’s more interesting to talk about how this provided an opportunity to change their lives”—to realize the American Dream.

A fellow graduate student at the Yale School of Drama turned her on to the subject about 15 years ago. “One minute we were taking medieval Spanish literature, and then [Jane] was stripping on I-90,” Shteir says of the radical career change. Already interested in ways women reinvent themselves, she added her newfound material and a dissertation on burlesque, the girlie show’s precursor, was born. A larger project followed. “There was no book on striptease,” she notes, “and it was totally uncharted.”

So Shteir started from the beginning, tracing the origins of striptease—women undressing on stage in performances both seductive and silly—to early 19th-century theatrical trends in Europe, such as romantic ballet’s scant costuming. Next came the long legs of the cancan, made popular in Paris and first described in 1848, and the Folies Bergères’s barebreasted spectacles.

An outgrowth of both the Folies and Broadway revue, striptease took hold stateside in the 1920s, “a powerful symptom of twenties decadence,” Shteir writes, “and the New Women’s sexual liberation.” “Tease” became a showbiz term, with burlesque numbers connected to American popular theater and not, she argues, “just pornography. They were definitely risqué, but not by our standards.”

In 1930 Variety reported: “Girls have the strip and the tease down to a science,” bringing “strip” and “tease” together in pop culturese. Soon glamour was introduced to the acts, and advertising, Broadway, and fashion began copying their performance style.

In the late ’30s a crackdown on indecency forced burlesque theaters to close, and stripping moved to carnivals, state fairs, and urban nightclubs. It became more associated with the gangster underworld. Still, striptease continued to thrive throughout the 1950s, even as modern pornography and publications like Playboy emerged on the scene.

The ’60s brought the joyride to a halt. “The sexual revolution made the whole idea of striptease ridiculous,” Shteir explains. Nudity “became both a symbol of free love and a mark of men’s oppression of women. ... The increasing presence of the mob in the nightclub industry also played a role in the disappearance of striptease from American culture, as did the diminishing amount of fabric in everyday fashions.”

While tracking stripping’s rise and fall Shteir profiles the women drawn into the profession, from the anonymous girl next door to starlet Gypsy Rose Lee. The art, she found, offered the possibility for reinvention and financial gain. “Many became wealthy or did OK,” she says, making hundreds or thousands of dollars a week. Striptease also could be a way out of an abusive situation or a rural life. “In some ways it freed them.”

The paradox of stripping is not lost on Shteir. “Striptease often measured women through the lens of men,” she writes. “Sometimes it illustrated what women wanted those measures to be, and other times it seemed more like a male rebuke of what women lack.” Either way, it “flaunted female sexuality...in spectacular forms.” She adds, “It seemed to be one of the only places where women could be sexy and funny at the same time.”

Such qualities have given striptease new legs. Neo-burlesque acts like the Pussycat Dolls, a popular cabaret show in Los Angeles, are part of a nationwide movement, Shteir observes. “Striptease just seems to have this incredible pull. I think it’s a search for something that’s authentic, erotic, but not porn.”

Shteir—a sometimes spectator, but never a participant—is still mulling over this new breed of bawdy performers and its cultural meaning. In the meantime, she reminds readers of those women who paved the way.