|

||

|

New library chapter

When President Robert Maynard Hutchins eliminated big-time football at Chicago in 1939, believing athletics detracted from academics, he effectively laid the groundwork for the University’s latest claim to scholarly fame: a 38,200-square-foot addition to Joseph Regenstein Library. Regenstein was built in 1970 on Chicago’s former Big Ten football stadium, Stagg Field, and this June’s decision to invest $42 million in a model research library, the largest North American collection under one roof, matches Hutchins’s dedication to the life of the mind.

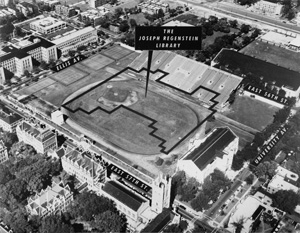

This 1965 photograph sketches the Regenstein Library’s imprint on

former Big Ten football stadium Stagg Field.

While the new Center for Integrative Science offers state-of-the-art research labs, “the library is the laboratory of the humanities and social sciences,” says Provost Richard Saller. “With careful planning we can make this the best, most efficient library for scholars to use.” Though scholarship is the priority, space considerations motivated the expansion. Back in the late 1960s the Regenstein’s original planners predicted the library would reach capacity around 1995 and saved land west of the building for an addition. Architect Walter Netsch even drew blueprints that maintained the Regenstein’s style.

Sure enough, by the mid-1990s space was scarce, and the library installed compact shelving in the basement, a stopgap slated to last about 12 years. Despite digital technology, Chicago’s print collection continues to grow by 150,000 acquisitions each year, so in June 2003 capital funds were allocated to study expansion options. A faculty committee convened, chaired by Richard Helmholz, the Ruth Wyatt Rosenson distinguished service professor in the Law School, and the University hired architects Shepley Bulfinch Richardson and Abbott as consultants.

Although Chicago already had campus space for an addition, the recent trend in expanding academic libraries is to warehouse much of the collection off-site—both because it’s cheaper and because many campuses have no more room. Harvard went the warehouse route in 1986, as did Stanford last year. The Chicago faculty committee, however, protested off-site storage. Browsing the stacks, they argued, benefits scholarship, and waiting for a requested book to travel back to campus is inconvenient. The challenge became finding a solution to satisfy both the faculty and the school’s pocketbook. (Considered a necessary upgrade, the expansion is exempt from a recent University policy requiring 85 percent of funding to be secured before construction begins.)

“In the initial planning,” Saller says, “the architects seemed to steer the committee into thinking off-site storage or on-site, compact shelving were the two options. The faculty opted for compact shelving, but the difference in price was a factor of four.” So he began to think about a compromise, “a hybrid to accommodate the faculty’s need to browse monographs,” or books.

In spring 2004 then-library director Martin Runkle, AM’73, visited the University of Nevada–Las Vegas, which employed an automated-storage-and-retrieval warehousing system that manufacturers have been using for 50 years. In the UNLV library system, users request materials via computer. The machine reads a bar code, and a robotic crane travels long aisles of four-story-high shelves, pulls the appropriate bin, and delivers it to a staff member. A user in the library receives the item in minutes. If a request is made outside the library, the item is waiting when the patron arrives.

Runkle returned to Chicago convinced a combination of stacks in the current building and the Auto Storage and Retrieval System (ASRS) in the addition was the answer. After a series of faculty and administrator UNLV visits, Saller agreed. But he wanted to know what portion of the collection would be stored in high-density, automated shelving. That decision was left to Judith Nadler, who became library director when Runkle retired last October. Nadler appointed a committee of bibliographers, which recommended that 75 percent of the serials, which have online tables of contents and article summaries, and some Special Collections materials—archives that get little research traffic—move to ASRS. Those two categories, the committee estimated, would fill the 300,000 linear feet of high-density shelving space.

After Saller approved the plan in November, he and Nadler presented the plan to the faculty. “The faculty in the humanities and social sciences thought it was in tune with their needs,” Nadler says. “It was a fast-paced but thoughtful and thorough process. And we have an elegant, forward-thinking solution.”

The addition can hold 3.5 million new volumes (the Regenstein now houses 4.5 million volumes). Construction should run $35.79 million, with $6.215 million for preparation and processing work. This fall a search committee, headed by Elaine Lockwood Bean, associate vice president for facilities services, will select an architect, who won’t be required to work from Netsch’s original plan. The committee, says Regenstein assistant director of access and facilities services James Vaughan, is “looking for an excellent design that is a creative and sensitive solution that takes into account function, context, and site.” Plans call for construction to begin in summer 2007 and to last two years.

In the meantime another faculty group, appointed by Saller and chaired by Andrew Abbott, AM’75, PhD’82, the Gustavus F. and Ann M. Swift distinguished service professor of sociology, is looking at how to improve Regenstein as a research environment. Members will consider how to best maximize library space and new digital capabilities.

Google’s late-2004 announcement that it would digitize the entire Harvard, Stanford, University of Michigan, University of Oxford, and New York Public Library collections, coupled with Chicago’s electronic efforts, opens new possibilities for complementary print and digital resources. “The shape of the digital revolution is unpredictable,” Saller says. “We don’t know how it’s going to evolve. Google may digitize millions of books, but there will be copyright issues. It will be great for virtual browsing, yet libraries will still need books. We’re planning for the next 25 years,” he adds. “That’s all we can reasonably anticipate.”