|

||

|

Features ::

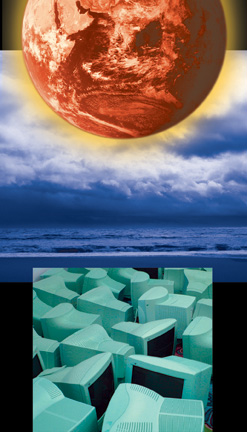

Heated Discussion

Why conversation about global warming is part science, part spin.

“Everyone

talks about the weather,” Mark Twain reputedly said, “but nobody

does anything about it.” Substitute “global warming,”

and the old saw becomes contemporary commentary. It’s been 15 years

since the United Nations–sponsored Intergovernmental Panel on Climate

Change, composed of hundreds of scientists worldwide, released its first

report suggesting that increased levels of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere

would affect the earth’s climate, perhaps catastrophically. Since

then global warming—a term first used in the 1970s—has come

to occupy a bizarre place in the public mind. A 2002 Harris poll showed

that 85 percent of Americans had heard of global warming, and of that group,

more than 70 percent believed that increased CO2

emissions were adversely affecting the earth’s climate. Yet while

there is strong scientific consensus and widespread public recognition of

the problem, there’s essentially no concerted action at the federal

level: President Clinton endorsed the Kyoto Protocol, an amendment to an

international treaty that instructs nations to reduce greenhouse-gas emissions

or engage in emissions trading, but CO2 levels continued

their rapid rise during his two terms. The record during the Bush presidency

is also dismal: on June 22, by a 60–38 vote, the U.S. Senate defeated

a proposal to cap greenhouse emissions at 2000 levels within five years,

and at this July’s G-8 summit American influence helped reject British

Prime Minister Tony Blair’s call for mandatory emissions limits in

favor of voluntary reductions.

“Everyone

talks about the weather,” Mark Twain reputedly said, “but nobody

does anything about it.” Substitute “global warming,”

and the old saw becomes contemporary commentary. It’s been 15 years

since the United Nations–sponsored Intergovernmental Panel on Climate

Change, composed of hundreds of scientists worldwide, released its first

report suggesting that increased levels of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere

would affect the earth’s climate, perhaps catastrophically. Since

then global warming—a term first used in the 1970s—has come

to occupy a bizarre place in the public mind. A 2002 Harris poll showed

that 85 percent of Americans had heard of global warming, and of that group,

more than 70 percent believed that increased CO2

emissions were adversely affecting the earth’s climate. Yet while

there is strong scientific consensus and widespread public recognition of

the problem, there’s essentially no concerted action at the federal

level: President Clinton endorsed the Kyoto Protocol, an amendment to an

international treaty that instructs nations to reduce greenhouse-gas emissions

or engage in emissions trading, but CO2 levels continued

their rapid rise during his two terms. The record during the Bush presidency

is also dismal: on June 22, by a 60–38 vote, the U.S. Senate defeated

a proposal to cap greenhouse emissions at 2000 levels within five years,

and at this July’s G-8 summit American influence helped reject British

Prime Minister Tony Blair’s call for mandatory emissions limits in

favor of voluntary reductions.

For those scientists convinced that the planet is headed for catastrophe, this do-nothing policy is hard to swallow. They’re equally frustrated by the arguments of a small yet vocal minority of researchers who maintain that inaction may be the right approach, strenuously attacking every facet of the global-warming argument. Some deny that warming is taking place; others deny that humans are to blame; still others say the climate will balance humans’ warming effect on its own, or the world’s citizens will simply enjoy slightly warmer weather. And so it goes, as the study of global warming links empirical scholarship and political involvement in way that can seem at odds with science’s long-standing ethos of free inquiry and dispassionate analysis.

Because the science and politics of global warming have so far gone hand-in-hand, professors who want to provide their students with an open, honest investigation of the phenomenon must help them to evaluate the competing practical data and theoretical predictions. And as they move from the scientific to the political sphere, they must help students to decide what solutions, if solutions are needed, are the most promising—and what their ethical obligations are.

In late April, 21 professors from 13 Midwestern colleges gathered at the University to wrestle with these issues as part of the Midwest Faculty Seminar’s Conference on Global Warming. The participants, who ranged in discipline from chemistry to economics to English, seemed, like the American population in general, largely in agreement that global warming is real and poses a significant threat. But just in case, Chicago climatologist Raymond T. Pierrehumbert—whose research focuses on climatic modeling and comparative analysis of the solar system’s different planetary climates—offered up a crash course.

The physics of the greenhouse effect are well established, Pierrehumbert began. Carbon dioxide, which is found in relatively tiny quantities in the air, traps some of the solar heat reflecting off the earth’s surface, raising the atmospheric temperature. “It’s like a blanket,” he explained. “A blanket doesn’t produce energy, but it reduces the rate at which you lose it.” Without that blanket, humans would freeze to death. Indeed, he said, carbon-dioxide emissions from volcanic eruptions are responsible for keeping the planet habitable. But there can be too much of a good thing—in this case, a blanket so heavy we begin to suffocate.

About 10,000 years ago, for reasons not entirely understood, the earth locked into a stable, habitable climate, a period known as the Holocene. Until recently, carbon-dioxide levels in the Holocene had consistently hovered around 180 parts per million (ppm), but when the industrial revolution fired up, humans began burning fossil fuels in massive quantities, releasing unprecedented amounts of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere. Today, carbon-dioxide levels are at 370 ppm and rising. “The 20th-century increase plots like a vertical line on a graph,” said Pierrehumbert. “Over the next 100 years we’ll put all of the carbon into the air that the earth stored over billions of years. So this is a big deal.”

Current climate trends support his “big deal” label. The data suggests that anthropogenic, or human-created, change has already begun. Since 1970, global average temperatures have risen by about one half of a degree Centigrade. The warming to come is on the order of 2 to 4 degrees C. If that doesn’t sound like much, Pierrehumbert put it in perspective: “By way of comparison, the number usually quoted for global mean cooling during the last ice age is about 6 degrees Centigrade.” The effects of the current warming, he pointed out, haven’t been uniform: “Winter has warmed more than summer, land has warmed more than oceans, and the Arctic—and parts of coastal Antarctica—have warmed a lot more than the global mean.” As a result of polar climate change, ice glaciers are receding, permafrost is melting, and in 2002 Antarctica’s Larsen B Ice Shelf, a 10,000-year-old mass the size of Rhode Island, collapsed into the sea.

But while scientists have little doubt that the greenhouse effect exists and that atmospheric carbon-dioxide levels are rising, they have considerable uncertainty about how such phenomena will affect the climate: how severe the warming will be, how quickly the effects will be felt, and, among some hard-core skeptics, whether it will change the climate in any significant way at all. Part of the uncertainty stems from the earth’s climate itself: a complicated and chaotic system makes accurate predictions difficult. Researchers still have many questions about the system’s switches and feedback loops, and, as Pierrehumbert noted, even something as basic as clouds presents problems for modelers because they are generally smaller than the smallest unit the simulations allow. Scientists can’t even agree precisely how clouds affect temperatures. “Almost all the differences in models,” he said, “are due to the difference in the way they handle clouds.”

Despite the difficulties, climatologists have learned enough to generate predictive estimates, that, although divergent, are not encouraging. Pierrehumbert illustrated the point using two maps, based on different models from the intergovernmental panel report, that coded temperature change by 2100 in hues ranging from cream for mild increases (1 degree C) to yellow, orange, and deep crimson for the most severe spikes, ten degrees or more. The first map showed warming around the globe, with more acute heating at the poles. The second map, what Pierrehumbert called “your worst nightmare,” was awash in searing yellow (3–4 degrees C) with the poles cast in a fiery red.

Faced

with such dire predictions, it might seem tempting for college and university

teachers to view each fresh group of eager undergrads as the raw material

from which they might craft the next generation of activists. Yet several

of the seminar participants expressed unease with how political rhetoric

has bled into the scientific discussions.

Faced

with such dire predictions, it might seem tempting for college and university

teachers to view each fresh group of eager undergrads as the raw material

from which they might craft the next generation of activists. Yet several

of the seminar participants expressed unease with how political rhetoric

has bled into the scientific discussions.

“While anthropogenic climate change may be happening,” Rebecca A. Roesner, a chemist at Illinois Wesleyan University, wrote in a pre-seminar posting, “I am troubled by society’s broad acceptance of this as fact—often with little appreciation for the available data or the ongoing debates within the scientific community regarding the cause of observed changes. Most of us do not have the geological and meteorological expertise to interpret current climate change in the context of the earth’s recent and distant past. Has too much of our academic discussion on global warming shifted from the geophysical and meteorological to the political?”

Roesner’s Illinois Wesleyan colleague, physics professor Narendra K. Jaggi, told the seminar about a lesson he’d taught in a freshman critical-thinking class, comparing the rhetoric used to argue for the Iraq war and statements urging action on global warming. With their shared emphasis on the possibility of future catastrophe, he pointed out, “the structure of the argument is very similar,” an overlap that, given the failure to find weapons of mass destruction, might make global-warming advocates pause.

The debate, of course, doesn’t happen in a vacuum. If global-warming activists tend to employ, as Jaggi said, “disproportionately strong adjectives disproportionately frequently,” it is likely because they are faced with a well-funded group of entrenched interests—what Illinois College physicist Frederick Pilcher called “big oil and big coal”—determined to protect their business interests by convincing the public that global warming is a myth. The May/June 2005 issue of Mother Jones reported, for example, that ExxonMobil has spent more than $8 million on grants to think tanks, institutes, and “skeptics.”

Yet not all global-warming skeptics are “bad actors” motivated by corporate largesse. Jaggi recounted a run-in with a colleague in the performing arts who offhandedly referred to Richard S. Lindzen, an MIT climatologist skeptical of dire climate-change warnings, as “a lapdog of Exxon.” As a result, Jaggi said, he dismissed his colleague’s own claims about global warming, seeing the name-calling as “inappropriate use of tarring by association and refusal to look at evidence.” David Archer, a University geophysicist who studies how carbon cycles through the oceans and the atmosphere, agreed with Jaggi that Lindzen, a contributor to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s 2001 report, is an honest skeptic, but he cautioned that others do qualify as “lapdogs of industry, who really try to muddy the waters and obscure things and confuse things.”

As an example of how murky the debate can get, Pierrehumbert displayed a 1997 Wall Street Journal op-ed with a headline proclaiming, “Science Has Spoken: Global Warming Is A Myth.” The piece was based on temperature data, gathered from a satellite and analyzed by University of Alabama researchers, that appeared to show a slight decline in global temperatures over the past 20 years. Subsequent researchers revealed methodological flaws in the analysis; when corrected, temperatures were, in fact, going up. The writers of the op-ed putting the nail in the coffin of global-warming theory turned out to be an eccentric biochemist named Arthur Robinson and his son Zachary, neither of whom has ever published a peer-reviewed work on climatology. In 1998 Robinson caused more controversy when his unpublished article debunking global warming, formatted to appear as if reprinted from the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, was circulated with a statement urging the federal government to reject the Kyoto Protocol’s emissions caps.

Like Pierrehumbert, Archer acknowledged the complexity of calculating the carbon-emissions threat. His own studies of the physical processes governing the life cycle of human-generated CO2 indicate that such gas takes thousands of years to dissipate. As he told a United Press International reporter earlier this year, “If one is forced to simplify reality into a single number for popular discussion” of how long human-generated carbon dioxide remains in the atmosphere, “several hundred years is a sensible number to choose because it tells three-quarters of the story, and the part of the story which applies to our own lifetimes.”

Although it’s difficult to pin down human activity’s effect on long-term global warming, it may be even harder to answer the question that logically follows: What is to be done?

While the conference attendees largely agreed on the ultimate goal—a drastic reduction of CO2 emissions akin to that called for by the Kyoto Protocol—two conflicting visions of a low-emissions world emerged: one techno-optimistic and one techno-pessimistic. The techno-optimists maintained that with the right policy incentives, global industrial society can continue pretty much as is, using technological breakthroughs to either replace the energy now supplied from burning fossil fuels or to perfect methods of capturing and sequestering the CO2 released so that it never hits the atmosphere. Techno-pessimists, on the other hand, maintained that there is no salvation waiting in the wings and that only societal reengineering can prevent global catastrophe.

Arguing diligently for the techno-optimistic view was Richard A. Posner, author of Catastrophe: Risk and Response (Oxford University Press, 2004). Posner, a senior lecturer in the Law School and a justice of the Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals, built his case on a straight economic framework: the aim of law and policy should be facilitating markets. In his view, global warming is an issue that the market, as currently constituted, isn’t well equipped to solve. The problem, he believes, has to do with the economic notion of discounting: a dollar spent in the future is worth less than a dollar spent today. So even if global warming eventually might prove to be massively expensive for private firms, they are still acting rationally by not spending the money now to solve or ameliorate the threat.

“If you think the most serious effects of global warming are going to be felt gradually over the 21st century, it probably makes sense to wait and see rather than to incur huge costs now,” Posner said. He moved past the why-spend-more-money-now-when-you-can-spend-less-later problem by focusing on the possibility of near-future, catastrophic climate change. “My interest in abrupt global warming might seem a bit perverse,” he admitted, “but I don’t really find the gradual global warming as interesting or as significant a risk to worry about. ”

Abrupt change is another matter. Climates, he pointed out, can flip very quickly. For example, Greenland ice records show that the island cooled or warmed as much as 10 degrees Centigrade over a century; already in the Arctic the pace of change has surprised even the most pessimistic observers. Abrupt climate change could result in a massive cooling of northern Europe, widespread flooding, drought, or any other number of catastrophic changes.

When

abrupt change becomes the focus of the discussion, Posner said, an economist

can make a robust case that government and industry should spend money now.

The costs incurred can be seen as a form of insurance, a way of hedging

against the possibility of sudden, devastating losses. Or they can be viewed

as an “option,” such as a studio might buy for a screenplay

it was interested in developing, which “enables you to postpone a

decision until you get more information,” Posner argued. “If

we impose emissions taxes now, that will be costly, but we can think of

it as an option that will buy us time.”

When

abrupt change becomes the focus of the discussion, Posner said, an economist

can make a robust case that government and industry should spend money now.

The costs incurred can be seen as a form of insurance, a way of hedging

against the possibility of sudden, devastating losses. Or they can be viewed

as an “option,” such as a studio might buy for a screenplay

it was interested in developing, which “enables you to postpone a

decision until you get more information,” Posner argued. “If

we impose emissions taxes now, that will be costly, but we can think of

it as an option that will buy us time.”

He remained confident that while developed nations will need to engage in concerted conservation efforts—more hybrids, fewer SUVs—technological innovation will ultimately allow the world to continue powering its current industrial economy. The prime goal of government policy, in his view, should be to find the right combination of emissions taxes (sometimes called “carbon taxes”) and investment in technological research to dramatically reduce emissions: hybrid engines, alternative energy sources, and carbon sequestration, which would capture CO2 and pump it far underground to be stored and sealed. Several conference attendees agreed that sequestration would be the keystone to any solution because even strategies that greatly reduce future emissions leave current CO2 in the air. “If I had to pick one possibility for saving us,” said biochemist Theodore Steck, who chairs Chicago’s environmental-studies program, “that’d be it.”

Not all the participants shared Posner’s optimism. Introducing his talk “Global Warming and Daily Life,” Chicago geophysicist Gidon Eshel quipped: “All we need is to simply change the way we do every last thing, to completely rethink every bit of societal infrastructure, and we should be all right.” More seriously, he continued, “The American way of life, and the way of life in many Western societies, is inherently incompatible with combating global warming.”

Eshel, who studies ocean-atmosphere dynamics and interactions as they affect climate, focused on the environmental implications of diet. Noting that 17 percent of the United States’ energy consumption goes to food production, Eshel argued that dietary choices could yield profound planetary impacts. Moving up the food chain, from grains to cows, for example, caloric efficiency diminishes dramatically. So while it takes a single calorie of input to produce 5 calories of oats, it takes 6 calories of energy to produce only one calorie of beef. Crunching the numbers, Eshel contended that diets rich in meat are needlessly wasteful, the dietary equivalent of “driving an SUV.”

The American diet’s energy inefficiency forms only one facet of a comprehensive way of life unrivaled in its energy profligacy. As Archer noted in his presentation, the United States consumes twice the energy and emits three times the carbon per capita as any other industrialized nation. If the whole world lived like Americans—who, with 5 percent of the world’s population produce 25 percent of the emissions—CO2 levels would be up to five times higher than they already are. What’s worse, Eshel said as he displayed a photo of two young Indian women in jeans, is that the “American way of life” is exactly what the rest of the world wants.

The hallmarks of economic development—advanced industry, transportation infrastructure, high levels of car ownership, and a broad middle class able to afford energy-consuming amenities—are inextricably linked to higher emissions. This fact presents a dilemma, highlighted in a preseminar reading, “One Atmosphere,” by Princeton University ethicist Peter Singer: it is clearly a moral good for more people in the developing world, particularly the destitute, to have access to increased wealth and amenities of the energy age, yet, as Singer notes, “[I]f the poor were to behave as the rich now do, global warming would accelerate and almost certainly bring widespread catastrophe.” How should global environmental policy finesse the trade-off between development and global impact? Naggi suggested that developed countries should help subsidize a cleaner energy infrastructure in the developing world because, as a practical matter, carrots are likely to work better than sticks. “India is building power plants to try to raise its GDP from $400 to $800 dollars [per person],” said Jaggi. “And if the United States with its GDP of $32,000 [per person] is going to say, ‘No, you can’t do that,’ I think they are going to make use of their 1.1 billion middle fingers. The United States doesn’t even have the pretense of moral leadership on these issues.”

Indeed U.S. citizens benefit greatly from the status quo, practically swimming in energy. If a serious emissions reduction means an America in which, as Archer put it, “we live a lot more like the French and Japanese,” then it will be necessary for teachers to educate their students about concrete, daily actions they can take to reduce their energy consumption: living close to work, driving a hybrid car, eating lower on the food chain. Peter Schwarzmann, a Knox College climatologist, has prepared a lab exercise in which students profile their own ecological footprints. “What I’ve found is that students hear all this stuff on the environment but they feel helpless,” he said. “This helps them realize that they do have power—whether they have the power to buy organic apples or to tell their congressman to support a carbon tax. There’s a sense that they have power, that they’re not helpless.”

That said, personal consumer choices alone are not going to solve the global-warming problem, and several participants pointed out that the most dramatic change in American energy consumption occurred during the oil embargoes of the 1970s, when high prices caused a drop in consumption and increased investment in efficiency. “None of us likes to pay more for anything,” said Kevin McMillan, who teaches political economy at Monmouth College. “We all understand that when we have to pay more for it, we’re going to buy less.” It follows, he continued, that one way to decrease carbon emissions is to adjust the price mechanism: “I don’t know how well carbon taxes work, but if we agree that something has to be done, that seems to be the way to do it.” Carbon taxes may not be politically viable in the near future, and McMillan, who served two terms in the Illinois state Senate, stressed that the impetus has to come from citizens. “It’s not the politicians normally—it’s the populace behind the politicians.”

“So what Kevin’s saying,” cautioned Steck as two shuttle buses pulled up outside the air-conditioned Regenstein Library to transport the attendees to their lakefront hotel, “is that we’re going to have to do our job a lot better if the populace is going to get smart enough to get the politicians to do the right thing”—no matter how complex the right thing may be.