|

||

|

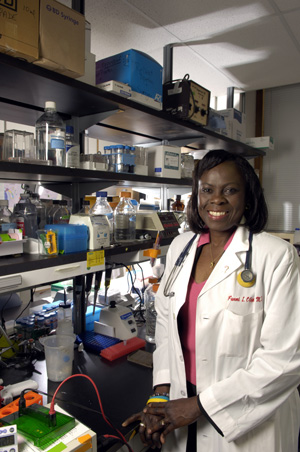

Breast-cancer crusader

Women of African ancestry are prone to a virulent

form of breast cancer—a genetic legacy that

Funmi Olopade hopes to challenge.

“There’s no excuse in the United States” not to screen

black women at a younger age, says Chicago’s Funmi Olopade. Africa,

she concedes, is another story.

Breast cancer can hit hard and fast, sending a patient scrambling for survival. In the race for a cure black females face especially tough odds. Women of African ancestry, a new Chicago comparison of African and North American data has found, are more prone to getting a virulent type of breast cancer than those of European descent. In such cases the tumors grow—and often spread through the body—quickly.

A positive diagnosis is not a death sentence, however. “It’s aggressive and curable,” stresses Olufunmilayo “Funmi” Olopade, professor of medicine and director of the University’s Center for Clinical Cancer Genetics. Knowledge is the first weapon in the battle against breast cancer, and Olopade’s team of researchers has made strides in understanding the disease. The team’s recent discovery, presented April 18 at the 95th annual meeting of the American Association for Cancer Research, is part of a larger U of C effort to learn why black females have an unusually high rate of breast cancer at a young age, compared to white women, and to address health disparities within diverse communities.

The disparities pose problems for both patients and physicians. In Africa, says Olopade, who grew up in Nigeria, doctors don’t have the resources to test what form of breast cancer women have. Despite those limitations, Nigerian researcher Francis Ikpatt had begun gathering tumor samples from the region. The tumors seemed different than those described in the literature—and worth a closer look. After seeing Olopade’s name on the Internet, Ikpatt wrote her. They decided to join forces, and he began a postdoctoral fellowship in her laboratory.

Ikpatt continued adding to the data stockpile, ultimately collecting breast-cancer tissue from 378 women in Nigeria and Sénégal. Back in the lab, Olopade’s team examined the pattern of gene expression in the tumors. Then the researchers compared the findings with a database of breast-cancer tissue from 930 Canadian women, compiled by Charles Perou from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, with colleagues there and in British Columbia.

The Chicago geneticists identified differences between the sample sets. Particularly troubling, the African tumors often lacked estrogen receptors. These ER-negative tumors aren’t sensitive to estrogen and thus don’t respond to drugs, such as tamoxifen, that work by keeping the hormone from reaching cancerous cells and stimulating growth. They also tend to be more aggressive. Without chemotherapy treatments most patients die within two years, according to Olopade. “I think the biggest challenge is this ER-negative breast cancer,” she says. “How should we screen for it and prevent it?”

Because ER-negative breast cancer moves fast, physicians must catch it early—and that means examining patients in time. Research shows that in Africa most breast-cancer cases occur around age 40, as opposed to the late 50s or 60s in America. African Americans, studies further suggest, are likely to get the disease between ages 40 and 50. Yet most U.S. screening guidelines, based primarily on Caucasian data, recommend an annual mammogram beginning at 50. Black women, Olopade says, should first get screened around age 25, and those who are high-risk—for example, women with a family history of the disease—even younger.

Female-health specialists agree. “That women of African ancestry are more prone to an earlier form of breast cancer that is particularly lethal and aggressive has major implications for policies and practices about breast cancer and its treatment,” says Sarah Gehlert, associate professor in the SSA and director of the University’s Center for Interdisciplinary Health Disparities Research. “The practice of screening after menopause, for instance, presumes that breast cancer is a postmenopausal disease, as it is in Caucasian women. Premenopausal breast cancer currently is not on our societal radar screen, which almost certainly adversely affects the health of African American women.”

For ER-negative patients, the stakes couldn’t be higher. “If they’re treated with chemotherapy and it’s caught early, they [can] survive,” Olopade says. “There’s no excuse in the United States” not to screen black women earlier. Africa is another story. There, she argues, “we really need to galvanize efforts to improve the research infrastructure and disseminate information.”

Olopade is working to close the knowledge gap in several ways, including teaching pathologists and residents at Nigeria’s University of Ibadan, where she received her bachelor’s and medical degrees, how to properly screen for breast cancer. She’s also working with government and drug companies to get treatments to Africans. Finally, she’s sharing the results from the study, funded by the Breast Cancer Research Foundation and the National Women’s Cancer Research Alliance, with her peers worldwide, including at the Fifth International Conference on Cancer in Africa this November in Sénégal.

“Now that we’ve identified this as a major problem, let’s get more research done,” Olopade says. Specifically, she wants to hunt down the culprit that forms ER-negative breast cancer. The disease appears to be associated with a mutant gene, BRCA1, but poverty and other environmental factors may also play a role. “We’ve got to take it from all angles,” she says. Working with colleagues at the Center for Interdisciplinary Health Disparities Research has convinced her that “there’s nature and there’s nurture” involved. “We don’t really know, but it’s probably a little bit of both.”

While the exact cause of the disease is unclear, Olopade remains confident of a cure. “Cancer doesn’t start overnight. If we understand who gets it,” she says, “we can develop strategies for preventing it.” Her ultimate goal is to prevent women from having “the same outcome their mothers had.” In case there were any doubts, she punches her fist and repeats, “We can cure it.”