|

||

|

College Report

Military man

Barefoot, in jeans and a T-shirt, with longish hair, John Schaeffer, ’08, looks the part of a college student. At 24, he has the apartment of one as well. “Sorry about the smell, we don’t know what that is,” Schaeffer says, acknowledging what might be the odiferous remnants of the previous tenant’s hamsters. He and his fiancée are still settling into their Lakeview studio, which features a window air conditioner, a futon, and a two-foot-tall stuffed bear.

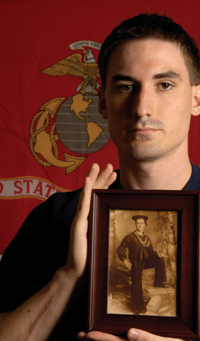

Schaeffer’s grandfather, in the Navy, was the last family member

before John to serve.

The role of college student is not always a natural one for Schaeffer. Having spent ten months overseas as a Marine, it is in his own country, at his own university, that he sometimes feels like a foreigner. Last year, Schaeffer recalls, quarterly registration was a lonely, confusing task. “I realized that I had a social-science requirement, but I didn’t know what social science was. I had gotten used to—from being in the Marine Corps—playing every situation by ear and figuring it out while I’m doing it. But I was totally lost, basically.”

Sitting on a wooden trunk that doubles as a coffee table, he admits, “I really had no concept of what being in college actually was.” As a first-year in Broadview’s Palmer House, Schaeffer noticed how academically groomed his classmates were. “I was surrounded by 18-year-olds who had spent a significant portion of their high-school careers getting ready to go to college.” It was a far cry from his own experience.

After graduating from a Massachusetts prep school in 1999, Schaeffer did not feel ready for college, and money was tight. Family legacy affirmed his academic ambivalence—his novelist father ran away from a British boarding school and never attended college, nor did his mother, and his sister dropped out of New York University to get married. His brother was the only family member to earn a degree—from Georgetown’s School of Foreign Service.

Schaeffer didn’t want to stick around his hometown of Salisbury, Massachusetts, and the military seemed a good way out. “I didn’t know anything about the military. I found out the Marine Corps was the most difficult [branch], and I thought if I was going to be doing something, I might as well do the most challenging thing,” he says. “At that point, I hadn’t thought much beyond boot camp.”

Those first 13 weeks remain a formidable memory, recounted in the 2002 book Keeping Faith: A Father-Son Story about Love and the United States Marine Corps (Carol & Graf). The book offers a detailed account of the Schaeffer family’s initiation into military life. He and his father alternate telling stories about Schaeffer’s months on Parris Island, including one of his most trying experiences—holding his breath in a small tear-gas chamber, the floor wet with vomit from previous recruits. The memoir also includes family letters and Schaeffer’s poems.

Four years into his Marine service, while deployed in Afghanistan, Schaeffer made a “snap decision” to attend college. “I knew I was coming home in a month,” he says. “I told my parents to get applications to all the places they thought would be good.” Returning home Christmas Day, he spent December 26, 2003, completing applications—to Chicago, Harvard, Georgetown, Columbia, and the University of Massachusetts—before leaving for Fort Meade, Maryland, where he worked in signals intelligence. “I figured as long as I got into a few places, that would be OK with me.” He wasn’t cavalier about going to school, but with nine months left of service he had “so many other things to think about at the time.” Without updated SAT scores, Schaeffer’s application was not considered by Harvard or Columbia, and he was rejected from Georgetown.

These days Schaeffer’s thinking is mostly academic. When not in class he spent much of last year in the library. This year he splits his time between campus and his apartment in Lakeview. For crunch periods like midterms and finals, his financial aid package provides him a room in Broadview, where he made “some friends and some nice acquaintances” last year.

Schaeffer quickly adjusted to dorm life; he was used to living in close quarters with a diverse group. While he’s enjoyed meeting other students, he’s been more impressed by the solitude he can create for himself at Chicago. “One of the differences between here and the Corps is if you want to isolate yourself it’s a lot easier to. You can have almost total privacy even though you’re in a dorm,” he says. “You can never go out and you can never see anybody, which isn’t really the case in the Marine Corps.”

Another difference between Chicago and the Marine Corps is the experience each provides. “In boot camp you never have to think of anything yourself. You don’t have a watch. Half the time you have no idea what time it is. If you want to figure out if it’s the afternoon or the morning you have to remember if you had lunch,” he recalls, “and it’s difficult to do sometimes.”

Schaeffer has found critical analysis a nice change of pace. “It’s a challenge for me to break out of my habit of just doing what I’m told.” One of his favorite classes was a humanities core requirement, Readings in World Literature, taught by Armando Maggi, PhD’95. “We would read 50 pages, but we would come in and spend the entire class talking about two paragraphs,” he says. “You just pick every sentence and every word apart, and I really love that.”

But that love has limits. “I appreciate the life of the mind, but if I’m not physically tired at the end of the day, I have trouble feeling like I accomplished something.” Taking his future in stride, he’s not concerned about plotting a career path before he graduates. “I joined the Marines on a snap decision. Went to college on a snap decision. I’ll do something after I graduate on a snap decision.”

Under his military contract, Schaeffer remains in the inactive reserve and can be called to duty until 4:30 p.m. on December 17, 2006, but he doesn’t fret over it. He enjoys being a Marine, and besides, he’s got more pressing things to worry about—like spring-quarter registration.