|

||

|

Features ::

Shticking to Their Puns

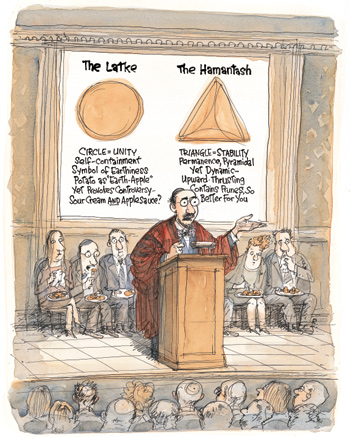

For nearly 60 years Chicago professors have gathered their wits and witticisms to debate The Big Question: Which is better—the latke or the hamantash?

You don’t have to be Jewish to enjoy the Latke-Hamantash Debate, but you do need an appetite for academic wordplay. A taste for latkes, hamantashen, or both also helps.

Hillel

House held the first debate in winter 1946. It was a time, notes Ruth Fredman

Cernea, editor of The Great Latke-Hamantash Debate (University

of Chicago Press, 2005), “when scholarly life discouraged an open

display of Jewish ethnicity. The event provided a rare opportunity for faculty

to reveal their hidden Jewish souls and poke fun at the high seriousness

of everyday academic life.”

Hillel

House held the first debate in winter 1946. It was a time, notes Ruth Fredman

Cernea, editor of The Great Latke-Hamantash Debate (University

of Chicago Press, 2005), “when scholarly life discouraged an open

display of Jewish ethnicity. The event provided a rare opportunity for faculty

to reveal their hidden Jewish souls and poke fun at the high seriousness

of everyday academic life.”

The debate is now an institutional mainstay, held the Tuesday before Thanksgiving and always in a packed Mandel Hall. The basics remain the same: distinguished professors take turns exposing their inner comedian, often neglecting to come down on either side of the question. Then presenters and audience decamp to a Hutch Commons reception to base their choice on primary sources. Some researchers opt for the latke, a round potato pancake traditionally served up at Hanukkah, the Jewish festival of lights. Fried in oil and accompanied by applesauce and sour cream, the comfort food commemorates the miracle in which a day’s worth of oil illuminated the temple for eight days. Others prefer the hamantash, a triangular pastry pocket (taschen in Yiddish and German) stuffed with poppy seed or prune filling. Hamantashen are associated with the spring festival of Purim, when Queen Esther and Mordecai saved the Jews from the evil Haman, who wore a three-cornered hat. Over noshes, the debate continues.

Destined to become the field’s standard reference, The Great Latke-Hamantash Debate offers a collation of past arguments, helpfully sorted into subspecialties (from “Metahamantashen, or Shooting off the Can(n)on” to “Semiotics and Anti-Semiotics”). And for the omnivorous reader, Cernea, an anthropologist who has written a study of the Passover seder, includes recipes—which can be found here.

The foodstuff of poetry—and verse

Remember Fats Domino? It can be revealed here tonight that to avoid anti-Semitic

prejudice in the r’n’r industry he had his name changed; it

used to be Shmaltz Domino. He, of course, sang the original version of “Good

Challeh, Miss Mollie.” And of course the ultimate Jewish cooking group

of the early Sixties were named simply the Challies. But their ethnic roots

did not stop with their name. No, their greatest hit was the ultimate lament

over one, well-formed matzah ball for another, less fortunate colleague.

Remember? “He ain’t heavy, he’s my brother.” I think

probably the entirety of the influence of Jewish cooking on early rock ’n’

roll (or latke roll, as we now know it) was captured by the Five Satins

(originally a Jewish group from New York’s garment district). They

sang a song that captured the culinary stresses of keeping kosher in an

increasingly secular world. The crossover version was known as “In

the Still of the Night,” but the original version went something like

this:

In gefilte the night

When I held you, held you so tight

And I really kept the faith

Promised I’d never, never eat traife

In gefilte the night.—William Meadow, professor of neonatology,

“Influences of Latkes, Hamantashen, and Jewish Cooking in General on the Roots of Rock ’n’ Roll” (1999).Though David admired Bathsheba’s torso

He liked her hamantashen more so.—Ralph Marcus, professor of Hellenistic culture,

“The Lovely Triangle” (1953).

(Hecuba enters. She is a mess. Her clothing is spattered with all sorts of gooey and sticky foods, among which egg and peanut butter can be observed; sugar and jam have clearly been thrown around, and stick liberally to the peanut butter. Around her waist are strapped cooking implements, including a spatula, an eggbeater, a long-handled fork, and a large pie knife.)

Up, unhappy head, up from the dust.

This is no longer Troy.

And I, Hecuba, was the chief cook of Troy.

Now we are routed by the Greek onslaught

that laid waste the gleaming kitchen of the kings.

—Greeks greedily gorging on my cakes

(both the round cakes and the sweet pointed cakes)

with a gluttony that knew no moderation.

Alas, the battle of the kitchen lost. Alas, my ruined royal

garments.

Yield to fortune, yield to spilled dishwater.

Don’t hold life’s prow against the swelling tide of garbage.—Martha C. Nussbaum, the Ernst Freund distinguished service professor in law & ethics

in the Law School,

“Euripides’ The Cooks of Troy, Hecuba’s Lament” (1997).

The dish on other disciplines

Psychologists tell us that our states of soul make the world, not the world

our states of soul; that, in Plato’s formula, latkes and hamantashen

are good because we are Jewish, not that we are Jewish because they are

good. You see the relativistic consequences of all that. If you think that

economists attribute nasty motives to human beings, wait ’til you

find out what psychologists believe.

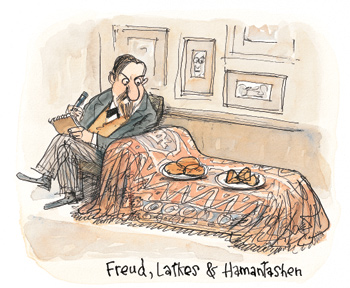

In truth they all follow their false messiah, Freud, who was secretly in the pay of, yes, the Manischewitz people, who out of economic motives wanted to spread the appeal of their products beyond the Jews and turned to the psychologist for help. So Freud, for popularity’s sake, interpreted the latke, the male, Maccabean food, as in its circular forms symbolic of the male goal—I need not elaborate on this lascivious suggestion; and the hamantash—the joyous token of Esther’s success, the female triumph—he explained by means of its angularity, its pointiness.

Propriety forbids my going further.

—Allan D. Bloom, PhB’49, AM’53, PhD’55,

“Restoring the Jewish Canon” (1981). Bloom, who died in 1992, was a professor in Social Thought and the College.

Rabbi

Leifer was kind enough to allow free access to the archives of Hillel, and

I was able to research past Latke-Hamantash symposia. I was curious as to

why, after 46 years of consideration and debate among members of our distinguished

faculty, such a crucial issue had not been settled. What I discovered, to

my utter amazement, is that this debate has been largely dominated by faculty

from the social sciences and humanities. Now anyone who has been through

a faculty meeting with these people knows quite well that they never settle

a damn thing, because deep down inside they just love to argue. That is

why the only real difference between a faculty meeting and a preschool class

is that the preschool class is run under responsible adult supervision.

Rabbi

Leifer was kind enough to allow free access to the archives of Hillel, and

I was able to research past Latke-Hamantash symposia. I was curious as to

why, after 46 years of consideration and debate among members of our distinguished

faculty, such a crucial issue had not been settled. What I discovered, to

my utter amazement, is that this debate has been largely dominated by faculty

from the social sciences and humanities. Now anyone who has been through

a faculty meeting with these people knows quite well that they never settle

a damn thing, because deep down inside they just love to argue. That is

why the only real difference between a faculty meeting and a preschool class

is that the preschool class is run under responsible adult supervision.

So, perhaps now it is time to settle, once and for all, the latke-hamantash question by putting it to the rigorous, objective test of the scientific method. What I will present to you now is not the empty polemic of philosophers, social scientists, and humanists, but rather the crystal-clear logic of science. I am afraid that many in the audience might be intimidated by science, so to make it easier for those of you who are used to the fuzzy, hazy, imprecise language of the social sciences, I will start with a brief guide to the precise langue of scientists to be found in the extensive Latke-Hamantash literature. For instance,

When it says:

“The hamantashen were integrated into the ambient background environment,”

it really means:

“The hamantashen were dropped on the floor.”

When it says:

“The latkes were kept isolated from adverse contaminants,”

it really means:

“The latkes were not dropped on the floor.”

When it says:

“Three sample hamantashen were chosen for further analysis,”

it really means:

“Results of the others didn’t make sense, so I omitted them

from the analysis.”

When it says:

“It is widely known that…”

it really means:

“I haven’t bothered to look up the original reference, but…”

When it says:

“The final resolution awaits further experimental data,”

it really means:

“The experiments didn’t work, but I need the publication for

a grant.”

When it says:

“I would like to thank Winstein for technical assistance and Friedman

for valuable discussions,”

it really means:

“Winstein did the experiment and Friedman told me what it meant.”

You see, science is not so difficult.

—Edward W. Kolb, professor in astronomy & astrophysics, the Enrico Fermi Institute, and the College, “The Scientific Method and the Latke-Hamantash Issue” (1992).

Freshly

baked scholarship

Freshly

baked scholarship

There is an unpublished and little known piece by Jane Austen.... It is

a sequel to Sense and Sensibility and Pride and Prejudice entitled

Love and Latkes, in which the sprightly young heroine comes to

discover that love lies heavy at her heart, and the rather less witty hero

finds out that latkes don’t sit so light in the stomach either.

The turning point of the action, so to speak, comes as the heroine is mixing a batch. While preparing the potatoes, she skins her knuckles on the grater. Leah—for that is her name—nearly falls lifeless to the floor, but Louis—for that is his—fearful that she will not finish with the cooking, catches her up and bears her to the sofa, to their mutual embarrassment but better understanding. This advance to happiness is delayed, in the succeeding chapter, when he begins to eat the latkes, eagerly and rapidly, in such immoderate quantities that, in Jane Austen’s proper words, he allows imperfectly articulated and indigested sounds of satisfaction to rise from his waistcoat and escape his lips. Leah is astonished at what, in her young and foolish prejudice, she perceives as grossness. “Had you behaved more like a gentleman, Sir,” she cries, “you would have apologized for this shocking indelicacy. Are you not sorry?” But Louis replies, as well as he can with his mouth full, “Latkes is never having to say you’re sorry.”

—Stuart Tave, the William Rainey Harper professor emeritus in the College, “Jane Austen’s Love and Latkes” (1982).

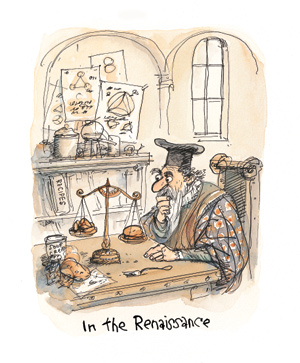

Although Machiavelli was a latke man, he has to be analyzed like a hamantash. This, among other things, makes him quite unusual. An example of such an analysis, although incomplete and basically inadequate, can be found in the work of the University of Chicago’s own Leo Strauss, learned also in Jewish philosophy, entitled Thoughts on Machiavelli. Strauss really went to town in pointing out that Machiavelli may never mean what he says; that the external surface hides a different meaning within, that he is master of deception....

Strauss also must be credited with opening up a splendid line of investigation in his theory of silence, which states, roughly, that it is all very well to read the words on the page, but what you should really be looking for is what the author does not say. That is where the true meaning is to be found: “The silence of a wise man is always meaningful.” Here, indeed, we have the key which Machiavelli scholars have ignored.

There are a lot of things about which Machiavelli is silent. Let us examine the internal evidence. He never mentions his mother. He never talks about cooking. He is silent about Hanukkah. The old deceiver, so fond of posing extreme alternatives and then coming down resoundingly on the unexpected side, never poses the antithesis of latke and hamantash. What does all this add up to? You’ve guessed it. Machiavelli was Jewish—his silence makes that crystal clear. Not only was he Jewish, he was, like all wise people, for the latke.

—Hanna Holborn Gray, president emerita, “The Latke’s Role in the Renaissance” (1991).

Taking issue with the issue

“Which is Better: the Latke or the Hamantash?” is not a valid

question, even though this has now been debated for 50 years.

* The question does not exhibit the necessary property of universality.

* It is culturally biased, implies gender specificity, exhibits geographical chauvinism and appeals to special interests.

* It is not value-free.

This question would not pass scrutiny on an SAT test, since it unfairly favors one ethnic and gender group over another: e.g., it favors the NY and Brooklyn establishment over the Midwest Rust Belt, and pits female latke workers against male hamantash bakers. In short, it is Politically Incorrect. Physics does not ask which is better: the proton or neutron, baryon or lepton, helium or neon, the conductor or insulator. These are simply properties of nature. Rather, physics asks: “Why?” or “Which is more important or more fundamental?” or “Who published it first?”

—Isaac Abella, professor of physics, “Grand Unification Theory: The Latke/Hamantash Paradigm in Modern Physics” (1996).

When in doubt, drop back and pun

To all who have experienced it fun heym aroys (“one from

the hearth”), Jewish food is no laughing matter. It is not so much

belly laugh as bellyache, a kind of hearth-burn, as it were. It could not

be by chance that the English translation of the letters on the dreidl,

the Khanuke top, spells out T-U-M-S. God may play dice with the universe,

but not with Mrs. Schmalowitz’s lukshn kugl, nor especially

with her latkes and homntashen.

—Michael Silverstein, the Charles S. Grey distinguished service professor in anthropology, linguistics, and psychology, “Heartburn as Cultural System” (1984).

The arguments in this article are excerpted and adapted from The Great Latke-Hamantash Debate (University of Chicago Press, 2005), edited by Ruth Fredman Cernea. © 2005 by the University of Chicago. All rights reserved.