|

||

|

Features ::

Photo Op

A University of Chicago Press editor confesses that even she—a fair-use crusader—has fallen prey to copyright greed.

As much as I exult in whining about big museums, there are obvious advantages to dealing with them. The staff is organized, they know what they are about, and they can communicate in a range of modern languages. Now and then, though, one must leave snug harbor and venture forth into terra incognita in order to capture just the right image. The scholar’s endeavor depends on it.

I’d like to be able to tell you that adventures in publishing carry editors to faraway places—and often they do—but transport is typically via fax machine or phone rather than chopper or jet. Yet, even bound to the desk, one does meet interesting people. Take, for example, my friend Brother Gregor. The occasion of our meeting involved a work by the Renaissance painter Antonello da Messina, an artist of great rarity, born in Sicily and trained in Naples, who, legend has it, may have introduced oil painting into mid-15th-century Italian art. Antonello is renowned for his practice of building form with color rather than with line like his contemporaries. His chromatic values are subtle, rich, elusive; his paintings exquisite and exceedingly scarce.

I’d like to be able to tell you that adventures in publishing carry editors to faraway places—and often they do—but transport is typically via fax machine or phone rather than chopper or jet. Yet, even bound to the desk, one does meet interesting people. Take, for example, my friend Brother Gregor. The occasion of our meeting involved a work by the Renaissance painter Antonello da Messina, an artist of great rarity, born in Sicily and trained in Naples, who, legend has it, may have introduced oil painting into mid-15th-century Italian art. Antonello is renowned for his practice of building form with color rather than with line like his contemporaries. His chromatic values are subtle, rich, elusive; his paintings exquisite and exceedingly scarce.

At the time of this story, a rumor was afoot of a long-forgotten Antonello, a Madonna and Child, in the sparsely populated mountains above the Sicilian port of Messina. I learned of the painting from an author who had decided she simply could not live unless she had it in her book, which was not about Antonello per se, but, as she explained, the image would be relevant all the same, not to mention a glorious coup, if we could be the first to publish it. Anyway, the more this author thought about it, the more convinced she became that the painting was crucial to her argument. No, she didn’t have a photograph of it but was absolutely certain she had seen it once, years ago, on an excursion to Sicily. No, she didn’t know of anyone else who had photographed it either. A photograph would have to be made. The painting was in a monastery, or had been—was it still?

A curious thing about Antonellos: as a rule, they do not reproduce well. Something about Antonello’s technique—so fragile really: the obsessive artist spent hours hunkered over his mortar and pestle, grinding, grinding, mixing. And he would take his works through the painstaking process of interlayering with a fine brush: first, the thinnest film of egg tempera alternating with one of oil paint, and then another layer of tempera followed by oil, over and over, hundreds of times, until the painting achieved a depth of color and reflection that few have managed to duplicate. The result is an image that seems so lush in the flesh but melts to mud in most reproductions, in part because these inspirations in pigment are not always lighted properly when photographs are made of them.

The painting of interest was in a tiny hamlet hidden in the Monte Peloritani above Messina. Antonello had returned to Messina toward the end of his life and had completed what scholars believe were a number of overlooked works still hanging in remote churches throughout the region.

This would be difficult. As my dispirited assistant put it, “a genuine pain in the butt.”

“Let’s think of it as a challenge,” I responded brightly, since the effort would fall upon her beleaguered shoulders rather than mine.

Days passed.

“Any progress?” I asked, peering out of my office at the assistant in her cubicle.

“I can’t find a photograph through any of the usual sources,” came the sour reply, then, added with a note of reprehension, “Please know that I’m doing my best.”

I said, “Why not phone the monastery and talk to the prior?”—a remark that elicited a sigh from the assistant, but who, bless her heart, nonetheless dutifully tried.

“No answer,” she announced.

“What time is it in Sicily?” I wondered, doing the math in my head. “Probably around five o’clock . . . time for vespers, yes?” What did I, a lapsed Episcopalian, know about vespers?

Assistant, being Roman Catholic, knew. She shook her head.

“Try again tomorrow,” I encouraged her, “but earlier in the day, when the monks are open for business.”

“You realize,” she was quick to remind, “that I don’t speak Italian, so maybe you should make the call . . .”

“If you insist,” I replied, a bit petulant, but at the same time secretly flattered. She had appealed to my vanity, the clever girl. I like to tell myself I speak Italian, but in fact I know only a few words—just a little tourist lingo—and I am bad on the telephone in almost any language.

The next morning at eight o’clock, I sat regally poised at the telephone. I had scrawled a few key phrases in Italian on a notepad and some technical details too.

I dialed.

“Hall-o,” came a voice on the other end of the phone.

“Mi scusi,” I began, and then plunged into the inevitable question: “Parla inglese? Do you speak English?”

“Eh?”

This wasn’t going to be easy. I tried other languages.

“¿Habla español?”

“?”

“Parlez-vous français?”

“????” . . . Silence.

“Sprechen sie Deutsche?” Heaven forbid. I didn’t spreche a word of Deutsche myself. Don’t know why I even asked, to tell you the truth.

Click. The phone went dead.

I waited a minute to compose myself, then dialed again.

“Mi scusi—”

“Rkt! Wg***$#%@@?!”

Click. Dead again.

I stared at the phone.

“Jeez, what language was that?” asked the assistant, who had been listening to the aborted conversation from her extension. “There weren’t any vowels. I’ve never heard anything like it.”

“Me either,” I confessed. “I’ll try again later. Maybe somebody else will answer the phone.”

Nobody else did.

But the voice, between calls, had hit upon a plan.

“Veni, vidi, vici . . .”

I summoned our classics editor, and without further ado, he and the voice in Sicily settled comfortably into Latin discourse. We learned that the voice was that of a Brother Gregor. Brother Gregor was a visiting Lithuanian curé who had been temporarily recruited to cover the monastery’s phone until someone more linguistically versatile could be engaged.

It is not so easy to discuss photography and modern currencies in Latin, but we made do . . .

“Madonna?”

“Madonna, aio.”

“Per Antonello?”

“Eh? Ah, aio.”

In the end, Brother Gregor acknowledged that, yes, indeed, the monks possessed the rare Antonello. No, they didn’t have a picture of it, but an appointment could be made to visit the holy painting. And if we wanted to photograph it, only a small donation would be required.

Good, I thought, because practically our entire illustration budget for the book would be exhausted hiring a photographer. (Silently I was berating myself for being such a softie when it came to this author.) Did Brother Gregor know of anyone local?

No? A pity. Then we would have to hire our own. Arrangements were made for a photographer we found through an agency in Palermo to travel to the site to photograph the Madonna. His journey, as it happened, was arduous and took several days: the road was so rutted and steep that the man had to travel the last ten kilometers or so on foot hauling his equipment uphill, piled on the back of an ass, and, unfortunately for us, he was being paid by the hour.

Commercial photographers usually insist on retaining copyright to their work, even when someone else has commissioned it; however, when I went to write the contract, I did my utmost to craft an airtight deal. I wanted to ensure that both the photograph and the negative would be our exclusive property. Yes, by god, we would be the ones with the goods this time; for once, we would be in the enviable position of licensing an image to others for reproduction; and we and only we would determine what fee to charge.

In short, two could play at this game. In drawing up the paperwork, I had several options, and, after some thought, I decided to go with a work-for-hire agreement. In such an arrangement, the author of a work made for hire is the person or institution who does the actual “hiring.” Normally, works for hire are prepared by employees of a firm, but if I crafted the agreement properly, the photographer might have no rights whatever in the work, particularly if I made it clear that the photograph would serve a specific purpose and was meant to supplement a larger work (the book, in this case).

I began to write:

Work-for-Hire Agreement

between

[the photographer]

and

[the publisher]

We mutually agree that the copyright to the photograph described in the purchase order attached to this Agreement will belong to the Publisher and that you hereby relinquish any and all claim to ownership rights in the work, a photograph of a painting titled Madonna and Child, by Antonello da Messina, located in the Capella di Santa . . .

I stopped, put down my pen.

Hmmm . . . should I really concern myself with the sticky matter of copyright? After all, I had always taken the position that reproduction photographs of two-dimensional artworks did not constitute creative work and thus were excluded from copyright protection. Perhaps I should simply avoid mentioning copyright altogether and, instead of issuing a work-for-hire agreement, which devolves from copyright law, style the instrument as a simple “all rights” contract, meaning it would specify that all rights to the work would belong to the Press, without actually naming them. Picking up my pen, I started again.

The Publisher commissions from you, for its exclusive use, photography, as described in the attached purchase order, of a Madonna and Child, attributed to Antonello da Messina, in. . .

My mind raced. I remembered that in an all-rights agreement, the photographer would be able to reclaim rights to the photo after 35 years, so on second thought, maybe it would be better to spell everything out plainly and in detail to prevent any misunderstanding. After all, we were spending a fortune to photograph that painting and were entitled to protect our investment, were we not? Think how much it was going to cost to rent that burro. In a sense, we were doing the world a service simply by creating the image and offering it for what would surely be a pittance compared with what it would cost others to photograph the painting themselves. Yes, and we were practically obligated to copyright our intellectual property for this was certainly a creative endeavor. Anyone could see that. What skill it would take to light the damn thing . . . hardly a job for an amateur. And then the photographer would have to set up the camera just so in that dark vault, select precisely the right lens and film. It took a certain—dare I utter it?—artistry to make such a picture.

On the other hand, didn’t I have a moral obligation to—? My head began to spin.

I stood up. Enough! What drivel! Of course we would copyright the photo. Like the very institutions I love to decry, I began to figure the angles. I calculated that once the word got out about this work, it would be really big news. We could license the image to the New York Times, to Apollo, to Burlington magazine . . . everyone would want a copy. Maybe even National Geographic would want to publish it. I began to wonder if there might be a way to prevent others from photographing Antonello’s long-lost masterpiece, even though, admittedly, it was in the public domain. Maybe we could convince the monks to post a sign at the entrance forbidding photography. And if we affixed a copyright mark to the photograph in the credit line, that meant we could prevent—or at least discourage—others from copying it out of the book we were about to publish. My brain worked harder. I would need to be sure to include in the photographer’s agreement a clause that enjoined him from ever making another photograph of the Antonello—would an Italian court honor such an agreement? I had no idea . . . I’d have to find out . . .

A lot of bother? You bet. And the day the image arrived was one in which I finally had to confront my own dimwittedness. The color photograph I pulled from the padded envelope was no more an Antonello than a Picasso. The picture featured a great ham of a Madonna with two pasty white blobs of paint for hands and an unfortunate child seated on her broad lap whose eyes were set too far apart in his head. It had none of the delicacy that characterizes the paintings of Antonello. It was clearly the work of an untalented amateur, probably from the 1950s. When I showed it to the author, she paled.

That was many years ago and an expensive folly. Yet even today I use the image whenever I can, which isn’t often because it’s just so incredibly ugly. Still, I try. When other editors amble into my office to brainstorm about possible illustrations for dust jackets, I bring forth the ersatz masterpiece.

“Have you tried the Antonello?” I suggest, as if it were a wine. “It’s very nice. Not to mention, excellent value for the money.”

If they hesitate, I place the picture reverently in their hands. “Anyway . . . here . . . it’s Ours.”

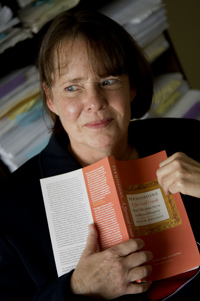

This article is adapted from Permissions, A Survival Guide: Blunt Talk about Art as Intellectual Property, University of Chicago Press, © 2006 by Susan M. Bielstein.

After two decades in art publishing, ten years at Chicago and previously at Rice University Press, Bielstein wrote Permissions to examine how art owners “overreach” their legal power and how the “image economy” affects “the ecosystem of arts and visual-cultural publishing.” Explaining both the legal issues (fair use, public domain) and how publishers go about their daily work (“you have to play ball” with museums, she says, “so they’ll work with you in the future”), she provides a primer for academics and other writers.

The need for such a primer has grown. “Over the last 15 to 20 years,” she says, “people have become more preoccupied with access and control.” The 1998 Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA), which bolstered Internet copyright protections, exacerbated the issue. “While the DMCA is meant to inhibit breaches in digital security,” she writes, “it does nothing to hinder content providers from locking down objects in the public domain by batching them with copyrighted materials and storing everything in electronic repositories with strictly controlled access.”

Writers and publishers also suffer from a lack of clear guidelines. Fair use, for instance, isn’t a law but a legal defense, and judges may define it differently. Moreover, “you see very little case law about images in artworks,” Bielstein says. “There is a lot of case law surrounding copyright infringement in the music and film industries because the stakes are higher—there’s big money involved. But only occasionally do the legal disagreements that arise in the trenches of art publishing make it to court.” Instead an assortment of “gatekeepers”—editors like herself who write contracts, university legal counsels, museum rights and permissions staff—interpret the law and “make dozens if not hundreds of judgment calls every day.” And though museums, she says, “rarely take a university press to court for what they see as an infringement,” they do file gratuitous cease-and-desist letters.

Progress, she says, is being made. In 2003 the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation funded a study on the health of the art-history field. This summer an early draft circulated (Rice’s press plans to publish the study) and was reported in the Chronicle of Higher Education. The researchers recommend, as does Bielstein, that art scholars establish statements of best practices for fair use, much as the academic Society of Cinema and Media Studies did in 1993. That group outlined scholars’ right to make limited use of copyrighted material, without permission, for the sake of education and criticism. “Members religiously protect this right,” and “to the best of my knowledge there has never been a lawsuit.” Another development: as Bielstein’s book appeared this spring, the Metropolitan Museum of Art announced a partnership with the Mellon Foundation’s ARTstor database to provide images—at no cost—to scholars for publication (their institutions must subscribe).

Don’t get her wrong: Bielstein isn’t against copyright. Writers and artists “should be paid for their work.” What she’s against are “the exorbitant fees exacted for a license. The fee,” she says, “needs to fit the project.”

Did her own money and effort fit the would-be Antonello project? Turns out, during the Press’s 2001 relocation across the Midway, the hard-fought image was lost.—A.B.P.