|

||

|

Citations

Origin of species

Even for simple organisms, the world is a global village, says Chicago geophysicist David Jablonski, and the tropics constitute biodiversity’s engine, churning out new species that later spread to higher latitudes. In an October 6 Science report, Jablonski and colleagues including University of California, San Diego, biologist Kaustuv Roy, PhD’94, trace 150 marine bivalve lineages back 11 million years, discovering that twice as many originated in the tropics as elsewhere. And while only 30 exclusively tropical bivalve varieties suffered extinction, 107 varieties died out after venturing out. The findings, which represent a decade of work, offer strong evidence, the researchers say, that preserving tropical environments is essential to sustaining worldwide biodiversity.

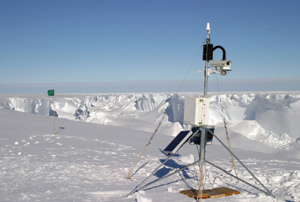

Web cameras help MacAyeal monitor ice movements like B15A's breakup.

No storm is an island

On October 21, 2005, a nasty storm struck the Gulf of Alaska, and six days later B15A, an Antarctic iceburg 8,300 miles away, shattered—disrupted by an ocean swell traveling from one end of the globe to the other, says Chicago geophysicist Douglas MacAyeal. In the October Geophysical Research Letters, MacAyeal and Northwestern geologist Emile Okal reported using seismometer data and wave-buoy records to track the swell’s advance through the Pacific Ocean. In Hawaii, wave heights rose by 20 feet when it passed, and three days later a seismometer on Pitcairn Island registered the swell’s arrival. The breakup of 60-foot-long B15A appears common, says MacAyeal, and raises questions about how storms driven by climate change might affect far-flung parts of the globe.

Origin of species

Ever since the 1949 discovery of insulin-degrading enzyme (IDE), a complex protein that does just what its name suggests, scientists have tried to decode its structure to develop new drugs for diabetes and Alzheimer’s disease. In the October 19 Nature, Chicago cancer researcher Wei-Jen Tang cracks the code. The enzyme, he and his coauthors report, looks like the video-game character Pac-Man: two bowl-shaped halves hinged on one side by hydrogen bonds. By introducing small mutations during interactions with four of the proteins IDE digests, the researchers increased its activity 40-fold in experiments that will yield blueprints for drugs to inhibit or enhance the enzyme.

The skinny on bariatric surgery

For the super-obese, gastric bypass isn’t the only surgical option. In the October Annals of Surgery, Chicago surgeon Vivek Prachand reports that a procedure called duodenal switch (see “Fat free,” April 2005) helps people lose more weight and keep it off longer. Prachand monitored 350 patients averaging 357 pounds and found that one year after surgery, gastric-bypass patients had lost, on average, 121 pounds, while duodenal-switch patients dropped 149. After three years, average weight loss for gastric bypass fell to 118 pounds, but for duodenal switch rose to 173. Prachand says surgeons often avoid duodenal switch because of its technical complexity: gastric bypass staples off much of the stomach and reroutes the intestines; duodenal switch leaves a larger stomach but alters the intestines more drastically.

Glucose tied to sleep

G etting a good night’s sleep can be medicinal for type-2-diabetes sufferers. In a September 18 Archives of Internal Medicine study, health-studies researcher Kristen Knutson focuses on 161 African American diabetics, reporting that those who slept poorly or too little (roughly three-fourths of study participants) had more trouble controlling their blood-glucose levels. For patients with diabetic complications like nerve pain, kidney damage, or coronary-artery disease, quality sleep was even more important—and yet more difficult—to achieve. “The magnitude of these effects,” she concludes, “is comparable to those of widely used oral antidiabetic agents.”