|

||

|

The root of the problem

Tina Rzepnicki uses root-cause analysis to help family-services programs work better.

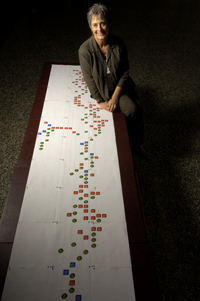

At the School of Social Service Administration, one of Tina Rzepnicki ’s color-coded “event trees” illuminates the actions and inactions that culminated in a child’s death.

One July evening four years ago, an eight-month-old baby—let’s call her Sarah—stopped breathing. Somebody dialed 911, the paramedics rushed to the home, but it was too late. They couldn’t resuscitate her, and the child died from asphyxiation. Her distraught father admitted fault. Frustrated because he couldn’t stop her crying, he’d stuffed baby wipes down her throat. When she began gasping for breath, he realized he couldn’t get them out.

Other details soon emerged: for two months before her death, Sarah had been the subject of an Illinois Department of Children and Family Services (DCFS) investigation, ever since her grandmother brought her to the hospital with bruises and a nurse called in a case of suspected abuse. At first the baby’s mother said her husband had hit Sarah, but later she claimed responsibility. Investigators took her at her word.

One of those investigators was a DCFS caseworker who had formerly served as a private therapist to Sarah’s mother and asked to be assigned to the family, believing her experience would be helpful. Having come to distrust extended family members during therapy sessions, she argued the infant should be kept with her parents instead of placed with her grandmother. When Sarah died, her mother was away at a parenting class, part of a custody agreement with DCFS officials who mistakenly believed she was the abuser.

“It’s a complicated case,” says School of Social Service Administration professor Tina Rzepnicki, AM’78, PhD’82. “It’s the kind of situation where there are multiple factors at work that led to this bad outcome.” To untangle those factors, Rzepnicki has turned to root-cause analysis, a process that traces an outcome to its most basic triggers: an unmade phone call, an unheeded order, a missing part, a miscalculated step. Used to assess airplane crashes, industrial accidents, and hospital mistakes, root-cause analysis is rarely applied to human services. Rzepnicki thinks it should be.

“There are a lot of parallels,” she says. “Any human-service agency that occasionally experiences tragic client outcomes needs a systematic way to take incremental steps back and analyze what went wrong. At each point in the chain of events, questions are asked, like, ‘What led to this event?’ ‘What contextual factors were evident?’ and ‘What things should have happened but didn’t?’” Rzepnicki, who with SSA colleague Penny Johnson, AM’71, PhD’01, published a study of root-cause analysis in the January 2005 Children and Youth Services Review, explains, “You look at each discrete point, rather than lumping it all together.”

Director of the University’s Center for Social Work Practice and, as of July, the SSA’s inaugural David and Mary Winton Green professor, Rzepnicki studies child protection, family preservation and re---unification, case decision-making, and clinical practice. She also is principal investigator for the Program Practices Investigation Project, run by the Illinois DCFS inspector-general’s office to examine and develop better child-welfare practice, and first encountered root-cause analysis in an article on failed military operations—missions doomed by bad decisions, bad communication, unforeseen or unforeseeable obstacles, errors of action and inaction. “Things started looking familiar,” she says, so she decided to test the method in the inspector-general’s office. Headed by Denise Kane, AM’78, PhD’01, the office examines child deaths—like Sarah’s—in families that have warranted recent DCFS attention. “What the inspector general wants to know,” Rzepnicki says, “is whether DCFS is in any way responsible.”

As an agency that, she says, “embraces learning from mistakes and problems within organizational processes,” DCFS seemed a natural fit for root-cause analysis, and three years ago Rzepnicki established a pilot program. Since then she has worked on a handful of cases, using a computer program that asks systematic questions about why and how specific events occurred to trace a situation backward. The labor-intensive process yields six- or eight-foot-long, color-coded diagrams resembling, appropriately enough, upside-down family trees.

“Pretty quickly you end up with a lot of these red squares, which highlight what didn’t happen that should have at a particular point in time,” Rzepnicki explains, noting that “hindsight bias” presents a constant temptation. “It’s easy to fault investigators for not knowing something they should have known, even if they couldn’t have known it at that point. That’s partly why it’s important to make this a group process, so that people can discuss and deliberate and keep each other on track.” The goal, she says, is to produce a report so objectively reliable that investigators working independently would reach the same results.

One difficulty, Rzepnicki says, is knowing when to stop. Follow a line of inquiry far enough, and “you always end up [making reform recommendations] at the policy level.” Yet sometimes what’s needed is a change in culture, not policy. “We find that with a lot of these cases, the mid-level is where a lot of shortcuts are being taken, or where there are disincentives for good practice.” Staffing shortages, for example, can make for overworked supervisors, pressuring social workers to close complex cases quickly.

As Sarah’s advocate and her mother’s former therapist, the caseworker investigating the child’s abuse felt torn between their conflicting interests, Rzepnicki says, and her supervisor, dealing with too many cases, failed to request reports on the mother’s mental history and the father’s prior violence, which might have raised an alarm. Deferring to the therapist-caseworker’s judgment, others didn’t verify the mother’s claims by talking to neighbors or family members. “These cases often hit the media with big, splashy headlines, and then a caseworker or two are held responsible, and after a flurry of activity a policy change might be made—sometimes without removing or revising the old policy,” Rzepnicki says. “If we make all our changes at that level, it’s not going to be that helpful for individual behavior.” Institutional culture matters.

Inspector-general staffers examine only disastrous cases, but Rzepnicki believes that looking at successful cases—children returned happily to reformed parents, children rescued in time from deteriorating situations—can point the way to practices worth encouraging. “What actions, what conditions, what decisions led to a good outcome?” she asks. Currently seeking funding for such an examination, Rzepnicki expects it to yield life-saving results.