|

||

|

Peer Review ::

Botanical inspiration

Artist and writer Hugh Musick never stops inventing.

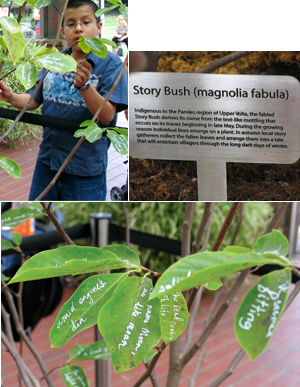

Turning over leaves (clockwise from top): a young museum-goer inspects

verses; a placard chronicles the Story Bush’s origins; poetic fragments

are inscribed in white lettering on the plant. Photography by Jenny Fisher, ‘07

This fall Hugh Musick, AB’84, became a story-gatherer. He collected leaves as they fell from his installation Story Bush (magnolia fabula), a Star Magnolia bush growing in Chicago’s Lincoln Park Conservatory since June 28, and transcribed the phrases he’d earlier written on every leaf. At each day’s gathering, Musick’s poem grew with a few more of the 255 lines he’d inscribed in June, including “unseen poetic acts keep the world afloat,” “anonymous,” and “the mysterious dirigibles of Mauritania.” The result was a poem whose narrative order was composed entirely by chance.

A self-described “editorial horticulturalist,” Musick, 44, pairs text and art throughout his work, and particularly in the almost 800 postcard-sized collages that he—a product developer in his day job—has made. Nearly all the collages feature Musick’s imaginative stories on the back. One recent piece combines an image of a wizened mariner, compass in hand, with a doll-like little girl. She clutches a bunch of grapes as he measures them. The reverse side tells the story of a girl whose grandfather “came of age during the Age of Scurvy” and insisted that she eat “at least thirty milligrams of fresh fruit each day.” He was convinced that “he could quantify exactly how much a single raspberry,” for example, “contributed to [her] growth.”

To create his collages, Musick gathers scraps of paper wherever he travels and trawls Web sites for digital photographs of antiques. He then arranges the images on paper or in Photoshop, forging an exchange between scissors, glue, and digital manipulation. Story Bush, Musick says, was inspired by one of his collages, itself prompted by seeing fiery red leaves in the fall. “The image of someone writing a whole novel” onto a plant “just came to me.”

When he’s not making collages or collecting images, Musick runs his own company, Springboard Product Development. His job is to “make abstract concepts tangible,” a role that “dovetails with the art” he creates. A favorite assignment was designing a giant zoetrope, which projects images through slits in a revolving wheel, for a toy store. Musick points out that his art, unlike his products, has “no commodity basis.” He’d never sell one of his collages, he says—only a reproduction. “They belong to my kids”—Morley, 12, and Eleanor, 10.

Musick remembers the first collage he ever made, a design with three pirates, pennies, and sandpaper, created for his three-year-old son in September 1997. That creation set Musick on a roll. In the late ’90s, while he traveled through Asia and Europe looking for source materials and new trends as director of product management for Chicago’s Amco Corporation, Musick found himself saving the postage stamps and newspapers he came across. He incorporated them into collaged postcards. On the front were surreal scenes of people and animals, and on the reverse Musick wrote letters to his kids, posing as the imaginary friend on the front. Back home, when they weren’t looking, Musick slipped the postcards in the family’s mailbox, addressed to Morley and Eleanor.

In 2000, after seeing a show at the Museum of Contemporary Art by drawing-collage artist Tony Fitzpatrick, Musick visited Fitzpatrick’s studio to ask how he could enlarge a collage he had made for his daughter’s bedroom. Fitzpatrick said, “This is serious art. How much do you want for this one?” Musick didn’t sell.

Two years later his collages were included in Scene in Chicago, an exhibition of local contemporary artists at the Judy Saslow gallery. Taking part in the neighborhood show was a great achievement for the self-taught Musick, but it meant he had to tell his kids the real story behind the postcards. Morley, who was 7, cried, while Eleanor, 5, called him a liar. But now, Musick says, “They just think it’s really cool” that he is the artist behind the scenes.

Story Bush, like Musick’s pirate collage, was something of a leap into the unknown. It was his first installation piece, not to mention the first time he worked with a plant. Now, Musick says, he’s inspired to try more installations, rattling off a long list. One he calls, What if a band played in the woods and there was no one there to hear them? A camera crew would start filming a band playing from very close up, then get incrementally farther away until it was filming people simply going about their everyday lives. Another idea would set up 200 custom-made punching bags in the atrium of a busy downtown building. He would love to see whether people were “compelled to hit it or look at it.”

Musick finds inspiration wherever he goes. “Everything is a blank canvas for possibilities,” he says, admitting that he has been inundated with ideas his whole life. Now that he’s become an artist, he’s found there’s nothing he’d rather be doing than making those ideas reality.