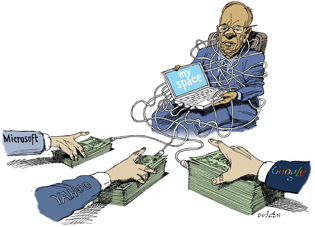

MySpace’s tangled web

Behind the scenes at a Rupert Murdoch executive retreat—and behind the backs of the MySpace founders—Google and News Corp. hammered out a blockbuster deal.

By Julia Angwin, AB’92

Illustrations by Dusan Petricic

MySpace’s perch atop the Internet is under assault. The social-networking site’s audience growth has stalled, its technology is outdated, and rival Facebook threatens to eclipse it. Three of its top executives departed in March, and MySpace cofounders Chris DeWolfe and Tom Anderson, whose employment contracts were set to expire this fall, left in April. At the same time, the News Corp. unit’s business has hit an advertising slump, and a lucrative alliance with Google Inc. expires in 2010. But three years ago MySpace clinched a deal that catapulted it into Web stardom, becoming the only social-networking site with significant revenues and profits.

It was a cool summer night, and News Corp. Chairman Rupert Murdoch was entertaining the rock star Bono with shots of tequila at the Carmel Mission Inn in Pebble Beach, California. Murdoch was at the famous golf resort to hold one of his trademark executive retreats, where he aims to inspire his lieutenants with fresh ideas from speakers such as the U2 front man and former British Prime Minister Tony Blair.

It was July 2006, and Murdoch was on top of the world—in large part because of MySpace’s success. ComScore Media Metrix data showed that MySpace’s monthly audience had more than doubled, to 54 million from 21 million at the time of News Corp.’s acquisition the previous September. Investors had bid up News Corp.’s stock while other media stocks were languishing. Behind the scenes, however, News Corp. executives were desperately trying to figure out a way to make money from My-Space’s large audience. MySpace was selling most of the ads on its site for low rates through so-called “remnant” ad networks and was earning an additional few million dollars a year from the ads that Yahoo placed near search results on MySpace’s site.

MySpace was also turning out to be very expensive to run. News Corp. had poured tens of millions of dollars into its infrastructure, but the site was growing so fast that it was still crashing regularly. To attract advertisers and to appease angry parents and lawmakers, News Corp. was investing heavily in pornography screening and other security measures.

Then there was the problem of integration. News Corp. had bought several Internet properties and had placed them in a new division, Fox Interactive, that would sell ads across all the properties. But many of those Internet properties, including MySpace, were chafing at losing control of their ad sales. News Corp. President Peter Chernin hoped to boost Internet ad sales at the new division by auctioning search-advertising sales rights to the highest bidder. Fox Interactive’s chief strategy officer, Jim Heckman, who was running the auction, predicted that by pitting the search engines against each other, Fox could raise $250 million.

The initial bids had come in a few days before the Pebble Beach retreat. Microsoft bid about $450 million, Yahoo bid $750 million, and the tiny search engine Ask.com proposed a joint venture. But the biggest player, Google, hadn’t submitted anything at all.

During the cocktail hour before Bono’s speech, MySpace cofounder Tom Anderson grabbed the legendary Silicon Valley venture capitalist and Google board member John Doerr, a nerdy-looking guy with a skinny frame and big glasses, and introduced him to Heckman. “Google didn’t show up with a bid,” Heckman told Doerr. “The number for you to be competitive is $750 million.” Doerr swung into action, calling Google cofounder Larry Page, who was vacationing in the south of France, and urging Google to get into the game.

After Bono’s speech, Doerr and Heckman rented a hotel suite, arranged a conference call with Google executives, and stayed up all night hammering out an agreement. By 6 a.m. they had drafted a one-page document outlining a $750 million deal between MySpace and Google. Heckman called the other search engines to tell them their bids had been trumped.

Tuesday morning was cold and foggy as the teams from Google and News Corp. gathered in a ground-floor conference room at the Inn at Spanish Bay, overlooking a fairway. Chernin took Heckman onto the golf course. He put his hand on Heckman’s elbow. “What do you need to get this thing done?” Chernin asked.

Heckman said he needed a small team of negotiators—he worried that involving too many players could slow down the focus and momentum of the deal makers. Chernin agreed and designated a small team of executives from Fox Interactive. In effect, the MySpace cofounders had just been sidelined from the biggest deal in their corporate history. To attend Murdoch’s conference at Pebble Beach, MySpace CEO Chris DeWolfe had even left his wife at home awaiting the imminent birth of their first child.

The tension between MySpace and Fox Interactive had been coming to a head for months. As it became clear that My-Space was the biggest and most important part of the division, De-Wolfe and Anderson were increasingly resentful of interference from their corporate overseers. At the same time, the executives at Fox Interactive were increasingly resentful that MySpace wouldn’t take any of their suggestions.

The dispute had spilled out in public in an April 2006 New York Times article about MySpace’s financial prospects. In an interview, the head of Fox Interactive, Ross Levinsohn, had suggested that MySpace could charge bands to promote concerts or sell songs on the site. In another Times story the next day DeWolfe dismissed the idea. “Music brings a lot of traffic into MySpace,” he said, “and it lets us sell very large sponsorships to those brands that want to reach consumers who are interested in music. We never thought charging bands was a viable business model.”

Fox Interactive executive Mark Jung was quoted suggesting that MySpace could sell profile pages to small businesses such as car dealerships. DeWolfe brushed off that idea as well: “If it was a really commercial profile—the gas station down the street—no one is going to sign up to be one of their friends,” he told the reporter. “There is nothing interesting about it.”

Levinsohn and Jung couldn’t force their suggestions down DeWolfe’s throat. But they did control advertising across all the properties, and thus they controlled the search-engine auction. This deal was their chance to prove the merits of Fox Interactive to the recalcitrant MySpace founders.

In retrospect, Heckman regretted not including DeWolfe and Anderson in the deal negotiations at Pebble Beach. “If I had it to do all over again, I probably would have involved them more,” he said later. “It was harmful from a relationship standpoint.” But at the time, Heckman said, he felt he needed a small team to get the deal done.

Meanwhile, Yahoo started backing away from its initial $750 million bid. Microsoft came around with a generous new offer: $1.12 billion in guaranteed payments over three years. But it included lots of conditions that MySpace was likely to reject.

Heckman told the Google team that its $750 million bid had been topped. He also said the competing offer was a giant hairball of conditions. “So if you can keep yours clean, you can still win,” Heckman said.

Working together, Heckman and Google’s top negotiator, Tim Armstrong, came up with a creative way to reach a suitable figure, $900 million: they extended the length of the deal from 30 months to 36 and expanded it to include international ad sales. Although less than Microsoft’s bid, Google put fewer conditions on its offer.

“You need to promise me in blood that you’ll stop all conversations with any other company if we agree to the $900 million,” Armstrong told Heckman. Heckman agreed. They shook hands and toasted the deal with glasses of red wine and hamburgers at the Pebble Beach golf clubhouse.

On Monday, August 7, News Corp. announced the deal after the market closed. Chernin bragged to the press that the Google deal paid for News Corp.’s $580 million MySpace acquisition in one fell swoop. Wall Street was thrilled. In after-hours trading, News Corp. shares broke through the $20 mark, an all-time high. Finally Murdoch’s conglomerate could prove that its nearly $1.5 billion Internet spending spree had been worthwhile.

“The size of this deal is staggering,” analyst Richard Greenfield at Pali Capital told the Wall Street Journal. “Twelve months ago, MySpace was generating $2.5 to 3 million dollars a month in advertising revenue. Now you’re talking about search alone being worth $25 million a month.”

That night Murdoch took his top digital executives to dinner at the Hotel Bel-Air to celebrate. But DeWolfe and Anderson, who were left out of the big-time deal making, weren’t feeling very celebratory. The Google deal interfered with another project the two were working on: an arrangement with eBay Inc. that would let MySpace users buy and sell items from one another using eBay’s online commerce tools such as PayPal. The Google deal, as drafted, would prohibit MySpace from working with eBay—and would likely force MySpace to use Google’s online payment system, Checkout, which was trying to gain market share from PayPal. De-Wolfe and Anderson would spend the next year battling with Google to amend the deal to get the eBay restrictions dropped. The delays ultimately forced Google to hold back its initial payments to News Corp. by a few months, and News Corp. extended the arrangement by an additional six months.

Even with the Google deal, MySpace has pulled in only thin profit margins. In the last three months of 2008, News Corp.’s Fox Interactive unit eked out a profit of just $7 million on revenues of $226 million, in part because of aggressive expansions by MySpace internationally and into a new music site.

But thin margins still put MySpace into a rarefied world of profitable Internet companies. It remains to be seen whether it can stay there when the Google deal expires next year.

From the Book: STEALING MYSPACE by Julia Angwin

Copyright (c) 2009 by Julia Angwin

Published by arrangement with Random House, an imprint of The Random House Publishing Group, a division of Random House, Inc.

Her space: An interview with Julia Angwin

By Jason Kelly

Photography by Dan Dry

On her MySpace page, Julia Angwin, AB’92, has 32 friends, the social-networking equivalent of desert-island isolation. It’s just not her scene, though she has tried her electronic best to find kindred spirits out there.

“This is after spamming everyone in all my different e-mail boxes. No one in my demographic is on MySpace despite the 75 million unique visitors every month,” Angwin says. “Everyone I know is on Facebook.”

She reflects the stereotype of Facebook, which launched in 2004—about six months after MySpace—exclusively for Harvard University students. Facebook established networks on 30 campuses nationwide, then more for high schools and corporations, before opening to everyone in 2006. Angwin, who has an MBA from Columbia University and shared a 2003 Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting as part of a Wall Street Journal team covering corporate corruption, fits Facebook’s educated, upper-class profile. She is connected in every sense of the word. By contrast, MySpace has a reputation for attracting an outsider audience.

In Angwin’s book Stealing MySpace—which chronicles how the site became a prized possession of Rupert Murdoch’s News Corp.—she quotes social-media expert Danah Boyd, of Microsoft Research New England, contrasting the sites: “The Goody Two-shoes, jocks, athletes, or other ‘good’ kids are now going to Facebook. … MySpace is still home for Latino/Hispanic teens, immigrant teens, ‘burnouts,’ ‘alternative kids,’ ‘art fags,’ punks, emos, goths, gangstas, queer kids, and other kids who didn’t play into the dominant high-school popularity paradigm.”

Those generalizations have blurred with the exponential growth of MySpace and Facebook. Global traffic on Facebook has more than doubled that of MySpace—276 million unique visitors to 124 million in February. MySpace still attracts almost 20 million more visitors per month in the United States, a significant advantage from an advertising perspective, but Facebook appears to be gaining. If sheer volume has watered down the distinctions, a cultural border continues to separate the two sites. “Whatever you want to call those cohorts, class or demographics,” Angwin says, “there is a difference.”

That difference is reflected in her small circle of friends on MySpace, though she still appreciates the site’s ethos of self-expression. “Facebook forces everyone into this template, and there’s not a lot you can do to decorate your page. I think people still do want to decorate,” she says. “Even I have sort of fallen for the MySpace thing and made my page into a whole bunch of pretty colors. If I could glitterize it, I probably would.”

Angwin’s book suggests MySpace’s initial surge in popularity happened in part because of that technical freedom, which the company’s programmers permitted by mistake. They forgot to block coding that changes the look of a page, granting every tech-savvy MySpace user a blank canvas that many readily adorned.

Things were just as colorful behind the scenes as the site expanded and the company struggled with increasing technological and financial burdens. After Murdoch’s $580 million acquisition in 2005, MySpace’s founders bristled as News Corp. helped them thrive but undercut some of their control. Reporting on that sale for the Wall Street Journal, Angwin learned details about MySpace’s halting start and sudden surge in popularity, which inspired her to write the book.

No MySpace or News Corp. representatives granted interviews or provided information about the intrigue that defined their courtship and uneasy marriage, the central narrative of Angwin’s story. Eighty-six pages of notes document her sources, which include internal memos and e-mails, filings from the Securities and Exchange Commission, and material from the New York attorney general’s investigation into MySpace’s previous parent company, Intermix, over its use of spyware and pop-up ads. Hundreds of interviews with people who knew the company’s culture and economic circumstances—former employees, venture capitalists, investigators—also helped her reconstruct the events of MySpace’s rapid, but fitful, evolution.

It turned out to be ironic that the rise Angwin recounts culminated with Murdoch’s purchase of MySpace. By the time she returned from book leave to her day job at the Wall Street Journal, the newspaper had a new parent company: Angwin now works for Murdoch’s News Corp. “I suddenly was in the position of having written this book that MySpace didn’t cooperate with and News Corp. didn’t cooperate with, and now I work for News Corp.,” she says. “So that’s a little weird.”

Wall Street Journal editor Robert Thomson assured her there would be no repercussions, and since the March 17 publication of Stealing MySpace, there have been none. “We’ll find out if I get fired,” Angwin says with a laugh, sounding confident that she has more friends in her corner of the Murdoch universe than on MySpace.