Sharp eye for Chopin

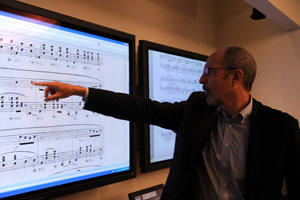

Jeffrey Kallberg, AM’78, PhD’82, shows Chicago music students how the composer's pieces were always works in progress.

By Elizabeth Station

Photography by Dan Dry

Sixteen graduate students stand over two musical scores in a seminar room at the Regenstein Library’s Special Collections Research Center. “Go ahead and turn the pages—don’t be shy,” says their guide, Jeffrey Kallberg, AM’78, PhD’82, an expert on the composer Frédéric Chopin. “I want you to get a feel for these things as material objects.”

Kallberg studies Chopin’s inclination to “monkey about” with his compositions.

On the right is a German first-edition of Chopin’s Piano Sonata No. 2 in B-flat minor, Opus 35, published in the early 1840s. On the left is a French version from about the same time. “I wonder if you can tell me what the important differences are in these two pages,” Kallberg says. Looking closely, the students find variations in the time signatures, tempos, and even the title of the third movement—called Funeral March in German but simply March in French. “So what does that tell you about how the piece would have been played in Paris as opposed to Leipzig?” Kallberg asks. “How do you make a version for a modern performer that takes into account these multiple editions?”

Performers seek out Kallberg when they have questions about interpreting Chopin, whose music was often published simultaneously in different countries with variant texts. A professor and chair of music at the University of Pennsylvania, Kallberg has examined nearly every Chopin manuscript in existence.

He has worked with the classical pianists Maurizio Pollini, Garrick Ohlsson, and former music and Committee on Social Thought professor Charles Rosen. Kallberg enjoyed a burst of renown in 2002 when he deciphered the composer’s early sketch of an unfinished prelude.

His book of essays, Chopin at the Boundaries (Harvard University Press, 1996), “totally revolutionized our ideas of how Chopin worked with materials and publishers,” says Robert Kendrick, professor and chair of music at Chicago. The book revealed “the social context, the domestic and not-so-domestic settings where his music circulated, which in some ways changed the cultural landscape of Paris in the 1830s and 1840s.”

On campus to give a lecture on “Chopin’s Pencil” during the University’s 500th convocation festivities, Kallberg has a long personal history with the Regenstein. His fascination with what he calls “the Chopin problem” began when he entered graduate school in the 1970s. Then, he says, the “hot topic for people interested in 19th-century music was compositional process.” Beethoven had been covered, and Mahler sources were hard to access, but Kallberg could compare Chopin scores in the library’s Rose K. Platzman Memorial Collection—a set of early editions of works by Romantic composers, compiled by geophysical-sciences professor George Platzman, PhD’47.

As a young scholar, Kallberg spent “countless hours” poring over the music. He laid eyes on his first original Chopin manuscript, a nocturne, across town at the Newberry Library. “It was very interesting, with lots of corrections and cross-outs and changes. It gave me the raw materials I needed to make conclusions about compositional process,” he remembers. “That’s how it all started.”

In his session with the graduate students—mostly PhD candidates in music theory and ethnomusicology—Kallberg hopes to inspire similar sleuthing. As they embark on their own dissertation projects, they may refer to Chicago’s Chopin collection, which includes more than 400 printed compositions to page through. “As far as I can tell,” Kallberg says, “it is the greatest collection of Chopin first editions outside of Poland.”

In 2009 the library staff finished digitizing those holdings for the Chopin Early Editions, an online archive for users worldwide to magnify, compare, print, and even e-mail scores. New works are added as they’re acquired.

Comparing print versions of nocturnes, ballades, and mazurkas, Kallberg offers theories about the composer’s inconsistencies. Even after sending a piece to the publisher, Chopin liked to “monkey about” with his compositions—altering notes to create different levels of dissonance, changing his mind about pedal markings, questioning an early creative choice and making a “fix” in a later edition. Publishing multiple versions of a score allowed Chopin to experiment and increase his income, Kallberg argues, and among Romantics, “it was never thought that you should play something just as it was written on paper. You had to bring something of yourself into it.”

Kallberg’s research has taken him in other directions—he has written articles about music, sex, and gender and published a widely performed critical edition of Verdi’s Luisa Miller—but it keeps leading back to the master. Chopin has a depth “which I seem never to fully penetrate,” he says. “I’m always hearing something new in the music.”

Return to top