Viva la revolución

With a veteran journalist as their guide, students dissect Cuba’s contemporary history.

By Elizabeth Station

Photography by Newscom

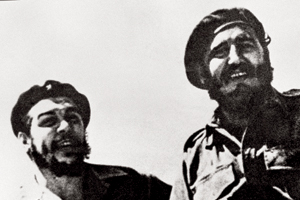

This class seems more cynical about Che Guevara and Fidel Castro, TA Patrick Iber says, than have previous students.

Looking for History: Violence and Revolution in Latin America meets only once a week, but it spans a continent. In this and every other session, visiting professor of history Alma Guillermoprieto has a lot of ground to cover. When she first taught the course in 2008, she began each three-hour class by lecturing. This year she’s trying something different: letting students teach for the first hour.

Focusing on one country at a time, in past weeks the students have examined drug and guerrilla violence in Colombia, the rise of Nicaragua’s Sandinistas, the 1980–92 civil war in El Salvador, and the formation of the Mexican state. Today’s topic is “Cuba: The Eternal Revolution.”

Dimming the lights, Guillermoprieto ducks into a rear seat. “Showtime,” she says, as the first trio of presenters comes forward. During their talk they project black-and-white images of José Martí, Fidel Castro, Ernesto “Che” Guevara, and other revolutionary heroes on a screen at the front of the packed seminar room. With changing sets of slides as a backdrop, three successive groups give rapid overviews of Castro, the socialist state, and the history of U.S.–Cuban relations.

Guillermoprieto slips easily into the role of observer. She made the first of many trips to Cuba as a dance teacher in 1970, and as a journalist she has reported on Latin America for three decades. She doesn’t interrupt, and she hasn’t required Spanish fluency for the course. Yet after weeks of discussing Latin American political upheaval with their professor—a Mexico City native—certain terms are common currency: patria, período especial, anti-imperialismo yanqui.

For some students, interpreting history isn’t as easy as deciphering language. “It’s hard to determine, when you read about Castro, what’s true and what’s propaganda,” says a spiky-haired man who has researched the Cuban leader’s early years. Discussing the U.S. trade embargo and its effects on the Cuban economy before 1989, a woman wonders “whether Castro really knows the extent of Cuba’s dependency on the Soviet Union.”

After the final speaker sits down, Guillermoprieto and teaching assistant Patrick Iber move to the head table to launch a broader conversation. “Why don’t we start with some of the threads from your discussion last night?” Guillermoprieto suggests, referring to the students’ online dialogue on the course’s Chalk site. “How do you keep a revolution going?”

For the Millennial generation, answers don’t come from experience. The 28-member class includes a few graduate students, but most are undergraduates—majoring in sociology, public policy, and international studies—born 30 years after Castro seized power in 1959. To prepare for today’s session, they have read the novel Yocandra in the Paradise of Nada (1997) by exiled writer Zoé Valdés; an excerpt from Guillermoprieto’s memoir, Dancing with Cuba (2004); and an essay called “Fidel in the Evening,” from her book Looking for History (2001).

The discussion begins cautiously; the students know that their professor has witnessed several revolutions firsthand. Her dispatches from Nicaragua, Brazil, and Bolivia have appeared in the New Yorker, National Geographic, and the New York Review of Books. Her writing has earned her a fistful of awards, including a MacArthur “genius” grant. As a stringer for the Washington Post during the Salvadoran war, she helped break news of the 1981 El Mozote massacre in the U.S. press. She’s interviewed Sandinistas, Zapatistas, and campesinos. At the invitation of Colombian novelist Gabriel García Márquez, she teaches an annual workshop for reporters at the New Ibero-American Journalism Foundation.

With a hint of deference, a young woman turns to Guillermoprieto. “I guess I wonder to what extent you think that the revolution is still going,” she ventures.

Guillermoprieto demurs, and a man in a blue fleece jumps in. “To what extent can you have a perpetual, ongoing revolution,” he asks, “if the definition of the term connotes a kind of overabundance of activity for a certain period of time?”

“For anyone under the age of 30, the revolution is purely discursive,” adds an under-30 woman named Bonnie Kate. “If you didn’t live it, if you didn’t hear the speeches, if you didn’t see Fidel when he was young and handsome and strong, how do you believe that this dying man is the father and leader of a future paradise?”

“It’s not just Fidel; it’s the state itself,” says a woman in a white knitted cap. “They made the effort at utopia, and it didn’t happen. So how could a young person believe in the revolution if the revolution happened and things didn’t get much better?”

Guillermoprieto tries to explain the left’s enduring fascination with Cuban socialism. “This is a model of change that dominated many of the brightest people’s thinking in Latin America from 1960 on,” she says. Turning to the blackboard, she lists ways students have described the early regime: Revolution not stable. Overabundance of activity. A march toward utopia. As the conversation continues, she adds what each item has become for Castro’s critics: Calcification. Boredom. Conservatism.

Iber, an advanced doctoral candidate in history, tells the students that they seem more cynical about socialism’s promise than those he taught five years ago. Why? “I hope this isn’t sacrilege,” responds a student named Rubén, “but the more I study Fidel and Che, the more I realize how inept these people were.” The 1953 attack on the Moncada barracks—Castro’s first attempt to overthrow the Batista dictatorship—was “stupidly planned,” he says. And Guevara’s foco theory of insurgency, via guerilla warfare, reveals “a tenuous grasp of Marxism.”

“I respect Fidel for his intelligence,” reflects a Latina student, “but the reason I’m disenchanted with him is that both he and Che did not know how to compromise.”

After a break, the class reconvenes for a final hour. Iber speaks briefly on U.S.–Cuban relations during the cold war, a topic related to his dissertation. Although Guillermoprieto spends most of the time listening, she weighs in with her own remarks. She notes that the course compares violence and revolution in seven countries, with earlier sessions focused on different national settings. So “why,” she wonders, “have we been talking about Cuba every single time?”

She offers a theory: “We talk about it repeatedly because Cuba is important in a way that Colombia or Peru will never be. We think about Cuba because Cuba changed its contemporary world. Not many countries do that,” she says, especially small island nations whose principal industries are sugar, tourism, and cigars.

“We have been looking at the influence of Che on guerrilla movements,” she continues, yet Cuba shaped Latin America and U.S. foreign policy long after Guevara’s death in 1967. Despite the Castro regime’s failings, its emphasis on health and education “raises the standard of what governments have to provide,” especially military dictatorships in the region, Guillermoprieto says: “Pinochet survives as long as he does because he increases the standard of living for Chileans during the time he’s in power. You could argue that Somoza and the Salvadoran junta fail to survive because they do not.”

With 20 minutes left, Ellery Biddle, a master’s student who recently returned from a research trip to Havana, provides a glimpse of Cuba now. Under Raúl Castro, Fidel’s successor, government critics face harassment and prison. The media is tightly controlled. But bloggers like Yoani Sánchez use the Internet to point out how the revolution has failed ordinary Cubans; dissidents distribute CDs of their writing on the street; an underground service called Granpa sends its own version of the news to Cuban cell phones.

As time runs out, Iber reminds students to e-mail him outlines for their final projects. Next week’s session covers Venezuela and Hugo Chávez. “To get a flavor of the man,” Guillermoprieto suggests students “go online and watch as many hours as you find interesting” of Aló Presidente, his weekly television show.

The class adjourns. Some students head down the steps of Cobb Hall. Others hang around to keep talking, proving a point that Guillermoprieto made earlier: Cuba “captures our attention and our imagination, and we care.”

Syllabus

By Elizabeth Station

Photography courtesy Alma Guillermoprieto

Based on “works of reportage by the instructor,” Looking for History: Violence and Revolution in Latin America explores contemporary themes in seven countries. The Center for Latin American Studies’ Tinker visiting professor, Alma Guillermoprieto is in her second of three consecutive years teaching the course, cross-listed in Latin American and Caribbean Studies, Comparative Race Studies, and Spanish. This past fall it met Wednesdays, 3–6 p.m., in Cobb 409.

Based on “works of reportage by the instructor,” Looking for History: Violence and Revolution in Latin America explores contemporary themes in seven countries. The Center for Latin American Studies’ Tinker visiting professor, Alma Guillermoprieto is in her second of three consecutive years teaching the course, cross-listed in Latin American and Caribbean Studies, Comparative Race Studies, and Spanish. This past fall it met Wednesdays, 3–6 p.m., in Cobb 409.

Texts include Guillermoprieto’s Samba (1990); Compañero: The Life and Death of Che Guevara by Jorge Castañeda (1997); The Massacre at El Mozote: A Parable of the Cold War by Mark Danner (1994); More Terrible than Death: Massacres, Drugs, and America’s War in Colombia by Robin Kirk (2002); and Five Families: Mexican Case Studies in the Culture of Poverty by Oscar Lewis (1975).

Grades are based on class participation (20 percent), students’ weekly posting and discussion of two “probing questions” on the course’s Chalk site (10 percent), small-group presentations providing context to analyze the week’s readings (30 percent), and a final research paper or other approved project (40 percent).

Guillermoprieto lives in Mexico, and teaching assistant Patrick Iber is finishing his dissertation from California. “Because both of your instructors are but wanderers passing by, and the duration of our dalliance with the University of Chicago is brief,” the syllabus warns, “we are unable to accept late papers this quarter.”