At the epicenter

On January 12, a 7-magnitude earthquake devastated Haiti, killing more than 200,000 people. In their own words, UChicagoans—scholars, medics, Haitians—share stories of that day and of the aftershocks that still reverberate.

As told to Lydialyle Gibson

Anesthesiologist Richard Cook was part of the University’s first medical relief team, which landed January 25 and set up a field hospital on the grounds of an orphanage in Fond Parisien, 30 miles east of Port-au-Prince.

Chicago anesthesiologist Richard Cook feeds Yyolson, an infant whose mother was killed in the earthquake and whose 22-year-old father fed him sugar water for three weeks until he could find help. The baby arrived at the Fond Parisien field hospital dangerously malnourished, but he recovered. “And his dad was able to take him home," says nurse Nicole Muse. (Photo courtesy Richard Cook)

At some level you have to come to grips with the fact that what you are doing is not making an enormous difference in the overall scale of the catastrophe. But you are making little, tiny deltas in little, small ways. And the things there are to do may not be things that you were thinking were your job. We put up a lot of tents. We put up a lot of cots. We put up lights. We cleaned toilets and picked up trash. Your professional skills may or may not be terribly useful at any given moment. I’m an anesthesiologist, and I didn’t do an anesthetic the entire time I was there. I did a lot of plain-old country doctoring.

There were moments that were deeply moving. The third night we were there, we were all exhausted and angry. I think everybody gets angry when you go there. You’re seeing so much suffering that you know you could deal with in your own setting. I mean, if all these people popped into the University of Chicago, their treatment would be considerably different than what we were doing for them there.

But then somewhere around the third day you stop being angry. You find something else to keep you going. You change your perspective from how unfair the world is to trying to make it locally better. As Pascal said, “Neither the sun, nor death, can be stared at too closely.”

It gets dark there very quickly because you’re closer to the equator, and the time between dusk and dark is very short. And when it got dark there, it was dark—no light, except what came from the moon.

So on the third night we were sitting around talking and going over plans for the next day, when the Haitians started to sing. [Chicago ER physician] Christian Theodosis said, “Listen.” And we all stopped. He said, “You know, they’re singing because they’re safe.” And they were safe—inside that compound. They weren’t going to get raped, or robbed, or stabbed. They weren’t going to die of starvation. They weren’t going to die of dehydration. It was a terrible place from our perspective, but on the scale of things happening around us, it was a good place to be. And they were singing.

The other moment came near the end. On Sunday we were going to go back to Santo Domingo, to fly out on Monday. You must remember that almost everybody in the camp came with nothing; they came out of some hospital or were carried out by a bus from some clinic. These people came with nothing, and most of them have nothing to return to. Their homes are gone.

Sunday Mass at the field hospital in Fond Parisien. “They hold a two-hour church service in the middle of Sunday morning,” says anesthesiologist Richard Cook, “for which everything else in the camp stops." (Photo courtesy Nicole Muse)

But on Sunday morning, all of a sudden, you see all of these people in clean clothes. Little girls are wearing white dresses. The boys are wearing ties. The men, many of them, are wearing white shirts and ties. Where did they get them? But here they are; they’re all dressed up because it’s time to go to church. And so they have church down at the end of the camp. They have a guy who comes in, and a little band. Some drums, a guy playing bass, another playing guitar, and a little amplification system. They have a priest and a bunch of people singing and chanting, and they have communion. They hold a two-hour church service in the middle of Sunday morning, for which everything else in the camp stops.

And people come down to this church service in wheelchairs, on crutches, with amputations. I saw a girl who had a high amputation of her left arm almost at the shoulder, and with her was her daughter or her niece, sitting in her lap. And they were both singing.

Chelsey Kivland, AM’06, an anthropology PhD student, was presumed missing for three days after the earthquake. She had been living in Port-au-Prince, researching Carnivál performance groups and their associated civic organizations.

Anthropology graduate student Chelsey Kivland, AM’06, with her friend Berman, who died in the earthquake. “I lost so many friends,” she says. (Photo courtesy Chelsey Kivland)

The earthquake happened in the afternoon. I had a meeting at 4 p.m. at the mayor’s cultural offices, and we were sitting on the patio when it started. Everybody just kind of stared at each other across the table and then seemed to get up really slowly and walk into the courtyard, just to try and get to the ground. And that’s when people started screaming, “Tremblement de terre!” Earthquake! Earthquake!

A few people who had run toward the building were injured, because the patio overhang collapsed. So pretty much immediately we were digging people out. It was a thin awning that fell, but one gentleman was pinned pretty badly. His shin had broken, and the bone was sticking through. Once we were out on the street, a couple of women did a makeshift tourniquet, and then he got on the back of a motorcycle. I don’t know where he was taken. I do know that he is alive and that he lost the bottom part of his leg.

I decided to walk home. It was only a ten-minute walk, in a neighborhood called Lalue, at the center of the city. But when I got to my street, I turned the corner and realized that my house was not there.

It’s a two-story building, and the second story just pitched forward onto the first story, which sunk into the foundation. There was a woman on the second floor watching TV when the earthquake struck. She literally fell to the ground and walked out onto the street.

My roommate, a University of Texas student, was in the house at the time. She’s from the Bay Area—thank God, because she knew what was going on. She got under a desk that was in a structural corner of the house. And the house did fall on her, but it buried her only from about the waist down. By the time I got there, she was nearly freed from the rubble by people in the neighborhood.

Kivland lived in Port-au-Prince for 18 months, researching a PhD thesis on the foot bands that perform at Carnivál and neighborhood festivals. The groups also run civic organizations that help manage schools and community restaurants and collect local trash. During emergencies, these organizations play a crucial role in funneling aid and information.

On our street alone, we counted—on a block with 16 houses—eight people who had died. In Port-au-Prince, you know your neighbors; it’s just part of life there. And without any kind of official response in those early moments, it was really important to have that familiarity. You knew who to ask after.

That first night we stayed in the street right out in front of the house. We weren’t able to sleep because we were in shock, and people were still stuck. We held a flashlight for people who were looking for others. The second day one of the women who operated a kindergarten on a nearby street invited us to sit with them in the play yard of the school, an old wooden house that wasn’t totally destroyed. At night they—wonderful, wonderful people—invited me to come sleep by them in a big, open lot. That night I was able to sleep.

There were aftershocks this whole time. It was hard to tell sometimes—there were also flashbacks that weren’t actually aftershocks. That second night I was woken up by people picking up their stuff and leaving. “Come on, we need to go. There’s going to be a tsunami.” There had been talk of a potential tsunami, and once someone said it, the rumor just spread. So we were running to get away from this tsunami, but then people started talking about a flood coming down the hill. None of it was real. Eventually we made our way back to the lot.

A Haiti native and NICU nurse at Comer Children’s Hospital, Nicole Muse grew especially attached to the children at the field hospital. “You see all these kids there, and what your own child has, they don’t’ have,” Muse says. “Maybe you can’t give them all the things they need, but at least you’re there physically for them. And mentally.”

Everybody was so on edge. There was this sense that nowhere was safe. Not that there was violence, but when the earth itself feels unstable, you run to where it would be stable. And in an earthquake, there’s nowhere to go. The whole earth is shaking. Where do you go?

The next day my roommate, who’d been pinned under the house, had bad scratches and bruises. Her legs were not working well. She wanted to see a doctor, and we’d heard people were being treated at the U.S. embassy, 40 minutes away. Our landlord was able to get some gas and drive us. Once we got there, we found out that you could be evacuated. Neither of us wanted this, but when we went out to meet our landlord, he had gone back without us. It was a miscommunication, but I think he, in his own way, wanted us to evacuate.

We stayed at the embassy two nights and then got on a small Coast Guard flight. You had no idea where you were going. On the plane, one of the Coast Guard soldiers, who was very sweet, stood up in front and said, “Welcome home. It’s good to have you.” That was huge. After takeoff he announced that we were going to Santo Domingo. I took a flight from there to New York.

I have so many friends back in Haiti. I try to call one person a day. Most of my friends are faring OK. They are able to find food and water. But my field site, Bel Air, was hit bad. Most people are sleeping in tents; many went to the countryside. I lost some friends. It’s been hard because I wish I could’ve been there for them—there was actually a funeral for my friends Berman and Nerlande a couple days ago.

Nicole Muse, a Haiti native who works at the Comer Children’s Hospital neonatal ICU, went to Haiti as a nurse and interpreter. She has made three trips to the Fond Parisien field hospital.

“The children are the ones who are going to need a lot of support,” Muse says. “They play everyday. I don’t think that deep inside they really know what happened to them. When you’re a kid, things happen. They just know they’re living in tents right now.” (Photo courtesy Nicole Muse)

When I got there, I didn’t know what to expect. It was chaos. Children with no arms, no legs. I worked in triage, where everybody comes through. I cried every day. You see people in tents, people who had everything and lost everything. Some lost their children. As a nurse you’re supposed to be strong. And these people are telling me stories: “I lost a husband.” “I lost a wife.” One lady I know lost three children. Sometimes the stories are so gruesome, you have to say, “I’ll come back.” Because it’s just so much to take in. But you have to be stronger for them. We worked long hours, 7 a.m. to 9 p.m., every day. You don’t even feel like you’ve been working. Because I speak the language, people would come to me: “Miss Nicole! Miss Nicole!”

I was also in charge of the children: unaccompanied minors and separated minors. Twenty-one of them. I made rounds every day, trying to find out how they’re doing, who comes and visits them. Because unaccompanied minors don’t have—I get so emotional about it—some of them don’t have any family or friends looking after them at all. Some of them don’t even want you to touch that subject. Some of them have lost a leg or a foot, and they have a lot of anguish because they don’t know if their parents want them. I had the mothers of two children, five and six, who wanted to give the kids away to an orphanage because the kids were missing legs. When the child is disabled, it’s hard to take care of them and also go out there and find a job. They feel like they have to choose.

Dan Schnitzer, AB’07, cofounded EarthSpark International, a nonprofit that builds supply chains in Haiti for clean, efficient technologies like solar lamps and biofuel stoves. After the quake, EarthSpark distributed solar lights to women in tents. A Carnegie Mellon PhD candidate in engineering and public policy, Schnitzer visited Haiti in March. Donate at www.earthsparkinternational.org.

After the quake, Dan Schnitzer’s (AB’07) driver René and his family left Port-au-Prince move to the south coast. “His wife and daughter, they’re OK,” Schnitzer says. “Their house is intact, but they don’t trust it.” (Photo by Dan Schnitzer)

Even before the earthquake, there was never sufficient electricity in Port-au-Prince. You would walk around at night, and street vendors would be selling toiletries or candy or food by kerosene or candlelight. This is the biggest city in the country, and they’re using the same technology as people out in the most rural areas.

The lamps we’re bringing in—with super-bright LEDs that last up to ten years—are being distributed to women living in tent camps. In precarious situations like this, the ability to turn on a light greatly enhances public security.

Since the earthquake there has been a great deal of psychosocial trauma in Port-au-Prince. I met with a friend, Herns Marcelin, who heads a research group called INURED. This February INURED fielded a 1,000-person survey in Cité Soleil, one of the most notorious slums in Haiti. Eight weeks after the quake, 72 percent of people had not received aid from any international NGOs. And 20 percent of the violent incidents have been rapes; 11 percent of the people surveyed know someone who has been raped. More than 50 percent said they are afraid to go to sleep at night. These statistics are staggering.

Part of the problem is the way NGOs engage—or don’t engage—with the community. In the first four days after the earthquake, before the international rescue response arrived, neighbors and friends and strangers—local people—saved thousands of lives by pulling people out of the rubble. The stories I’ve heard are incredible. And there’s still tremendous potential. Community-leadership forums are being held, even in Cité Soleil. Unfortunately, this goodwill and leadership is being squandered.

International NGOs each have their own way of distributing aid—first come, first served, or tickets in exchange for aid—and what’s happening in Cité Soleil, which has a population of 300,000, is that gangs and other opportunists are hoarding aid tickets and demanding sex or exorbitant amounts of money in exchange. If NGOs were to engage with the legitimate community structures, they could improve these terrible statistics and cut the gangs and other opportunists off at the knees, allowing the aid to have its intended effect.

Fourth-year Adama Wiltshire founded UChicago for Haiti Relief to raise money for Partners in Health. By March her group, with help from 20 other student organizations, had raised $10,000—plus $10,000 in Medical Center matching funds. Visitors can donate at magazine.uchicago.edu/haiti.

I’m not Haitian. I’m Trinidadian, and I’ve never been to Haiti. But my family brought me up with an awareness of Haiti’s historical and social significance to Caribbean people. Long before many diaspora people thought about what it meant to be independent, to have a sovereign, self-determined nation, Haiti was years ahead. I’m talking 200 years ahead of Trinidad, which got its independence in 1962.

At the same time, I was aware that a lot of people throughout the world act as if Haiti doesn’t belong or doesn’t exist. I know people are saying, “America this, America that,” but it’s not just Americans; it’s Caribbean people as well. Haiti is literally a hop and a drop away from me in Trinidad, and I’ve never been there, but I’ve been to places like Norway; I’ve been to Vienna. So that’s problematic. And that’s one of the reasons I was happy to do this.

The morning after the earthquake, I started asking around, asking the African and Caribbean student associations on campus, “Are you guys doing anything?” I called members of the Puerto Rican Students Association. We started raising money the day after the earthquake. We had already booked tables in the Reynolds Club that evening. Within two days we had more than 1,000 people signed up on Facebook for a fundraising event. It was amazing.

Just seeing different groups on campus saying, “No matter how small it is, we’re going to give; we’re going to move and try our best to do something”—that was more than overwhelming. One girl on south campus, her dorm raised close to $500. I don’t even know what they did. All I know is, I got an e-mail that said, “We’re having a teach-in on Haiti, and can we give the money to you?”

Andrew Grene, AB’87, was one of 101 United Nations workers killed when the U.N. headquarters collapsed. A political-affairs officer, he was the son of late Chicago classics professor David Grene and alumna Ethel Grene and the father of students Alex, ’12, and Patrick, ’11. In Grene’s memory, his brother Gregory established the Andrew Grene Foundation to fund education and microfinance in Haiti. Gregory talks about his brother’s life and work.

Andrew Grene (left) and his twin brother, Gregory, during a 2009 visit in Port-au-Prince. “He loved the spirit of Haiti,” Gregory says. “It was a place full of joy for him.” (Photo courtesy Gregory Grene)

Andrew would come back from war zones with paintings he had found from some budding artist in a marketplace. He would be full of joy and excitement about the potential of the territory he was working in. This happened regularly, whether he was working in the Central African Republic or Ethiopia or Eritrea or East Timor—or Haiti. He’d say, “Look at this. This is who these people are; this is what can be done.”

And Haiti’s history during the time he was there proved him absolutely right. When he arrived in 2006, they handed him a flak jacket and helmet as he got off the plane, and there were bullets pinging off the car on the way to the U.N. mission. He never told us this. By the time I visited in February 2009, Port-au-Prince had a lower crime rate than other Central and South American cities—a low murder rate, a low kidnap rate. That’s one of the sad things about the earthquake: it’s put at risk something that was built up very painstakingly.

The United Nations had a memorial service in New York in March. It was a really moving thing, and the final touch of the day was a meet-and-greet. These things are usually people standing around sipping their bubbly water—they don’t have a huge amount of meaning. But in this case, person after person would look at me across the room, and the expression on their face would change as they thought that they saw my twin brother. Then they would come over and start talking about him. Without exception, it was a sequence of the most extraordinary, genuine tributes, whether from Haitians or people in Bill Clinton’s special-envoy office, people who worked with him at the United Nations in New York, people now in Afghanistan.

He consistently moved people, and they loved him for it. He saw the good in people, and they saw the heart they were dealing with.

Medical Center pharmacist Dima Awad spent ten days in February setting up a pharmacy at the Fond Parisien field hospital. A French speaker raised in Lebanon, she became a favorite of the orphans and young patients, who followed her through the camp as she worked.

“The kids were smiling, you know?” says Chicago pharmacist Dima Awad. “I’m not sure if I would have the strength after all they went through. But they smiled and played in the afternoon.” (Photo courtesy Richard Cook)

It looked like an impossible mission when I first arrived. There was no pharmacy, just chaos. Hundreds of boxes of drugs from all over the world, and every one with 300 kinds of medicines in five different languages. Some were expired; some packets were empty. We had to go through every single one. We were working around the clock. Sometimes I would sleep four or five hours, sometimes not at all.

André Jean was our carpenter. He built the pharmacy. I’m not sure how they found him, but he came, and we showed him the plan, and he brought the wood. He lost all of his tools in the earthquake. He had lost everything. He lost his wife. His two young daughters were in casts. He would come to me every day and say, “Dima, I can’t sleep at night. Give me something. I can’t sleep.” He was traumatized.

André worked with me from 6 a.m. until 10 p.m. every day. When he built the first wall, I cried. It was like, “Oh my God, this is really happening.” André hugged me. He hugged me every day after that.

The kids were smiling, you know? I’m not sure if I would have the strength after all they went through. But they smiled and played in the afternoon—I’m talking amputated kids. There was also a lot of psychological trauma, of course. Sometimes at night I would wake up and hear people screaming in their tents.

We’re not talking about a few months of helping these people out. It’s going to take 40 or 50 years. Much of the population is disabled. How do you fix that? I think we’ve focused enough on what we have done. Now we should focus on helping the Haitian government maintain what we have started.

James Toussaint, AB’00, was born in Haiti and grew up in south Florida. An orthopedic-surgery resident at Massachusetts General Hospital, he arrived in Haiti with Harvard doctors nine days after the earthquake. Part of his mission was to find his missing relatives: his mother’s brother and sister and their families.

On the first day, I threw down everything and tried to contact my family. Cell phones were the only way. But I couldn’t reach them. So I went to the general hospital and joined up with the surgeons there.

All we could do was triage. We’d walk through these tents of sick people lying on the ground or on ironing boards or wooden doors, and we would select the ones that were operative candidates. Meanwhile, others kept coming because they heard that the foreign doctors were around. People had broken bones, crushed limbs, extremities that needed salvaging or amputating—not to mention impending infection and sepsis. It was pretty dire.

On the second day I was able to reach my aunt and her children. They came and met me—you can imagine the tears and the hugs—and I gave them a package of nonperishables I’d brought from the States. It’s funny, I used to be a Boy Scout, so I just brought everything that I used to bring on camping trips: peanut butter, granola bars, crackers, mosquito repellent, those canned-tuna meal kits that have the tuna with crackers and a bit of relish. And I gave them some money so they could take care of themselves. They’re living in tents now.

My mom told me my uncle and his kids had died even before I could look for them. She hadn’t heard from him, and she said she didn’t think he was alive. We haven’t heard from him since, so—I guess by now we should expect the worst.

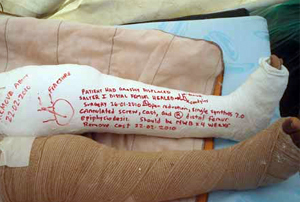

A makeshift medical record. The first wave of trauma surgeons who came through after the earthquake sometimes left explanatory notes on patients’ casts for the physicians who would come after them. (Photo courtesy Richard Cook)

After I talked to my aunt, I hitched a ride with some other doctors up to St. Marc, 100 or so kilometers north of Port-au-Prince, in an area largely untouched by the quake. I met up with the rest of the Harvard team, and we were able to arrange a makeshift operating room, a mini acute-care unit like you’d see in the States. Once we had it up and running, patients as far as Port-au-Prince—the ones that were able to survive the trip—came on the backs of mopeds or trucks or cars. It got to the point where we were doing 30 to 50 cases a day.

Amputations were difficult. In the United States, if a doctor says you need an amputation, that’s understood. In Haiti, even if a patient has no neurovascular function in their limb, if it appeared to be alive, Haitians did not want an amputation. People were saying, “The foreign doctors are here to cut off your limbs.” But being a Haitian who spoke Creole—someone who looked like them and was an orthopedic surgeon—I could say we were treating them the same way we treat patients in the States. I told them, “We’re not going to amputate any limbs without your permission.” It helped them trust us.

For me, the allure of medicine was always to have a profession that would be useful to people back home. When I got back to Boston, I told my wife that if I never end up practicing, I would still be one of the happiest guys in the world because I was able to do this.

Anthropologist Greg Beckett, AM’03, PhD’08, lived in Port-au-Prince between 2003 and 2006, studying crisis in contemporary Haiti. He was there during the 2004 coup that ousted Jean-Bertrand Aristide. An assistant professor in the College, he sees the earthquake as part of Haiti’s “long emergency.”

This is one of the worst disasters in modern history, and it renews our attention to the fact that emergency response is always most necessary in places with structural problems: deep poverty, social exclusion, weak infrastructure, political violence, unstable governments.

Haiti is a classic example of a layer upon layer upon layer of crisis: massive environmental crisis; complete collapse of the economy; weak, if not failed, state institutions. It’s often said that Haiti is the poorest country in the Western hemisphere, which is true, but it’s been the poorest country for decades. And it’s gotten poorer. Haiti’s GDP before the earthquake was less than half that of the second-poorest country, Nicaragua.

I think there will be a second and third wave of this crisis. The rainy season started early this year—it’s been raining almost every night since February, and it will continue through the summer. The mountains surrounding Port-au-Prince are completely denuded, so there are massive floods and mudslides. And people are living in makeshift shelters of cloth and wood. They don’t have floors. So surviving the rainy season will be an issue.

Then there’s the threat of a drug-resistant TB outbreak in the tent cities. And you’ve got conditions for the spread of malaria and dengue fever. And on top of that, food and water issues. All of this is delaying even a conversation about how to rebuild in Port-au-Prince.

You hear about the NGO-ization of Haiti; the effect is that the only groups that have provided food or water or electricity, or built a road, or dug a well, have been foreign nongovernmental groups. People fear that Haiti will slip into becoming a U.N. protectorate or a neocolony of the U.S. Neither the U.N. nor the U.S. wants that, and Haitians certainly wouldn’t accept it. It’s anathema to their nationalism, their deep-seated pride in the Haitian Revolution. Any direct foreign involvement in political affairs is immediately rendered illegitimate. But the fact is, the Haitian government can’t rebuild itself. It doesn’t have the funds, the equipment, the personnel. Matching the facts with the desire for a Haiti-led rebuilding will be a challenge.

But there’s a real moment right now to say, how do we prevent Haiti from being reproduced exactly as it has been for so long? The international community has committed itself to responding to this catastrophe. If Haiti simply gets rebuilt as the poorest country in the region, it would show a real lack of imagination and political will. This is the moment.