The journey home

A father and sonís ride back from college, recalled in the authorís recent book, becomes immersed in meaning.

By Mark Freeman, PhDí86

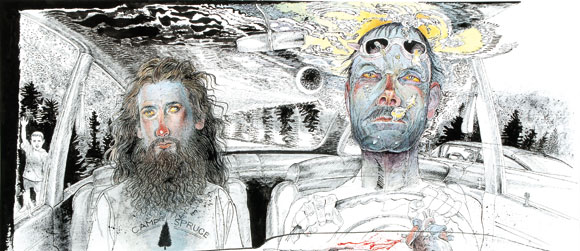

Illustrations by Jack Unruh

Adapted from Hindsight: The Promise and Peril of Looking Backward, Oxford University Press, 2010. Mark Freeman is a professor of psychology at the College of the Holy Cross.

My father could scarcely have imagined that I would someday be writing books. In fact, there was a sizable span of time during which the distinct possibility must have been raised in my family that, whatever I would do in life, it would be precious little. I don’t want to create the wrong impression here. It’s not as if I was condemned or considered a blot on the family name or some such thing; I was loved, cared for, played with, and all the rest. But my dad died very suddenly when I was quite young; I had just turned 20. And at that particular time, given the kind of life I seemed most interested in living, it simply wasn’t clear yet how everything would turn out.

Part of the problem was my age. I have two older brothers, one eight years older and one six. By the time I graduated from high school, they were each married, were beginning to build their own families, and, in general, were well on their way to becoming “established.” The oldest one had graduated from Georgetown and NYU Law and, despite having been something of a radical in college, which occasionally made for some rather heated exchanges with my father at the dinner table, had eventually gotten it together. And when he and his wife produced a beautiful baby girl early in July of 1975, in the bloom of summer, all of that tension seemed to melt away. As for my other brother, who had been valedictorian of his high-school class, who had graduated something-or-other cum laude from Yale, who had gotten married to a Wonderful Girl from a Good Family at age 21, who had gone on to Harvard Business School, only to land shortly thereafter at Procter and Gamble, where he would market diapers for the nation’s young and helpless, the only thing he was missing was a Purple Heart or a Presidential Medal of Honor. He was a dutiful son too. Not too long after I was appointed an assistant professor, he told me that he would have sooner thought I would be in jail than in a classroom. He said it with a smile, but on some level he meant it. Not only was I the baby of the family, who had been spoiled, “got away with murder,” and so on, but in his eyes at least I had been something of a wild man, who had already done some things that he himself would never have dreamed of doing, particularly given the much-mythicized wrath of my father.

The myth goes something like this: My two brothers, living under my dad’s reign of terror, had been forced to walk the straight and narrow path; when they were my age, there had been no room for shenanigans, back-talk, broken curfews, or anything else that gave the slightest hints of disobedience or disrespect. By the time I came along, my dad had mellowed a bit, the times were a-changing, and, by my brothers’ account, my life had been one great big fun-fest, in which I had been able to do everything they had not. Set in contrast to the clean-shaven family men my brothers had become, I must have seemed like a different kind of creature altogether. There is a picture of my father and me—I was around 18 at the time—in which we’re standing outside on a sunny winter day. He’s in a woolen coat, strong and serious, with a thick mustache, gazing sternly at the camera. I’m standing apart from him, in a two-tone suede jacket, hair halfway down my chest, with just the tiniest smirk on my face. In some ways, we were worlds apart.

I fear I might be giving the wrong impression again. It is true that my dad had a temper. He never, ever laid a hand on any of us, but the way he would sometimes yell at us, like he was ready to boil over with rage, would actually lead us to wish he would just whack us and get it over with. So there is no denying that he could be a pretty tough character. But he was also funny and charming, passionately in love with my mother, warm and affectionate with his children, playful with the family dog, greatly enamored of food and drink and nice clothes and traveling and dancing and many other things besides. For all of his rage and occasional sullenness, he was immensely entertaining, a larger-than-life figure with a great sense of humor. And he kissed me, or I kissed him, each and every night before bed, for as long as our lives intersected. There was tenderness and the smell of shaving lotion and a sense of real—albeit unspoken—connection. It was so long ago: 35 years now. Why did it have to be? Why? The death of a parent can leave wounds that never fully heal.

For a while, during my youth, everything no doubt seemed kind of touch-and-go to my parents. In tenth grade, an able but not exactly driven student, I became a member of a “gang” of sorts—not a chain-wielding, black-leather-jacket gang but a good-time gang, a bunch of guys who became bonded together in friendship and, every now and then, mayhem. We called ourselves the “Misty Mountain Maulers,” Misty Mountain having been taken from the pages of Tolkien’s The Hobbit. We had special shirts made up (I still have mine) and commenced what we called a “Viking Feast,” a bacchanalian food-and-drink fest which, as it turns out, we have held every year but two since 1971.

There were a few serious crises. I, for instance, was almost killed in a car accident the summer after 11th grade—intensive care unit, critical condition, lots of broken bones, the whole bit. My dad passed out cold the moment he saw me. I wouldn’t wish it upon anyone, but some good actually came of it. For one, some of the incessant squabbles my parents and I were accustomed to having, over topics ranging from my hair to my politics, vanished for a while; seeing their baby boy looking like a piece of raw meat, laying motionless in a hospital bed with tubes everywhere, they could only count their blessings that I had come out of the whole thing alive. For another, I myself learned that being at death’s door does give you some new things to think about.

The second crisis happened at the end of my senior year, when the founder of the Misty Mountain Maulers, who had gone on to MIT, where he became a basketball star, prankster, and budding intellectual in good standing, died, wasted, from cancer. The five remaining Maulers were thrown for a loop. We would still have our Viking Feasts, still play ball into the night, still drop sarcastic lines, and so on. But things were different. For a good while afterward, I was aimless, a kind of nomad, moving through people and places and things without quite being there. Much of that period is difficult to recall.

When I got to college at SUNY Binghamton the following fall, I took a few interesting courses, made some new friends, had a couple of short-lived but entertaining relationships, and spent a great deal of time listening to extremely loud music in the poster-strewn dorm I lived in with my frazzled roommate, who, rumor had it, had ingested so many powerful mind-altering substances that his hair and beard had just plain stopped growing. He did eventually go on to graduate school at Harvard to study architecture, so apparently he managed to retain some functioning brain cells beneath all that hair. In any case, things were OK back then, but as I can see now, in hindsight, just OK. I missed too many classes, which was a big mistake; I got so-so grades and was actually relieved about it; and I really didn’t connect at all to what I was learning. The D– I received on my first college essay had put some fear into me, and it was a bit disconcerting to try to learn the contents of an entire course in a night or two. But none of this had been enough to shock me into getting serious about school. So, the first year was OK, but again, just OK. Something was missing, and I could feel it in my gut even then.

Sophomore year was different. First, I had met someone—a free-thinking but serious anthropology major, interested in poetry and dance—who helped me get some of my priorities straight. In addition, I found myself gravitating toward an intellectual crowd, for whom Eastern philosophy and modern fiction were often the topics of the day. A group of us moved off campus the second semester of that year; as far as we were concerned, we had exhausted the dormitory scene and decided that living in a house together, communally, was a far more cool thing to do. We were all remarkably proud of that house, despite the fact that it was a dump. I, in particular, was so proud that I immediately invited my parents up for the weekend, so they could behold their independent, intellectually cutting-edge son’s wonderful new abode. My mother remained quiet, in a “This is nice, dear” sort of mode. My father, on the other hand, was horrified. Sleeping on an old mattress on the floor of my bedroom, which I had (unconsciously) painted the color of Howard Johnson’s—orange ceiling, turquoise walls—was one thing. The living room furniture (“Oh, the people down the street were throwing it out, Dad”) was another. My bearded, shoeless, yogi-like housemates, wafting about like so much vapor, was another still. My parents fled as soon as they possibly could.

But something strange and wonderful happened that spring, when my dad picked me up at school to take me home for summer vacation. The two of us were alone in a car for four hours—something that had never happened before. And he and I talked with one another, about college, about life, about ourselves, two men, father and son, making up for the strains and silences of a lifetime. He didn’t tell me straightaway—he was never given to that sort of direct disclosure—but right then and there he let me know, as best he could, that I was all right, even with my shaggy mane, weird friends, and dilapidated house. He could tell, I suppose, that I was in the process of heading somewhere and that I would probably turn out all right. When I was off working at a camp that summer I even received a letter from him, in which he basically said that it had been a pleasure to meet me and that he was confident that things were, in their own way, progressing nicely. He couldn’t possibly have had any idea at all about what I would do in the world, concretely. I didn’t either. But there were hints that it might be something. I do wish that he could have seen what; not unlike my brother with the jailbird fantasy of my future, he probably would have been quite surprised.

It was only a brief while after receiving that letter, that seal of approval, that I received a call in the camp’s kitchen from my oldest brother telling me that dad was gone. He had been at my uncle’s pool, swimming, and his heart had seized on him and wrenched his life away, just like that. Thirty-five years ago, this man I loved and in some ways barely knew, my father, who had just yesterday, or what seemed like it, sat and talked with me for the first time, who had uttered words that would echo through the years, speaking what I came to think of as “the presence of what is missing.” The ride home: this “incident,” such as it was, may appear entirely too fleeting and undefined to serve as a focal point for an exploration of hindsight. I cannot recall the details of our conversation, formative though it seems to have been. I cannot remember which car we drove or which route we took home or where we stopped to eat. It is all a blur; there is almost nothing. And some of what I do recall is, in a certain sense, impossible. As I look back, I can see the two of us in the front seat; I can see myself turning my head his way, leaning toward him. He doesn’t quite look back, his eyes remain on the road, but he’s fully there, doing what he can to connect with me. It is as if this picture is taken from the back seat, off to the side, or somewhere near there. There’s the steady hum of the road underneath, and the scenery flashes by, like time. Something is condensed in this scene, something unspeakable, that has raised it to the level of a kind of mythic moment, a founding moment, that ended up inaugurating an entirely different way of thinking about him, me, and the relationship between us.

An important fact ought to be acknowledged here. Had my dad not died, suddenly and inexplicably, two months later, this incident I have been at pains to recount would have had far less power and privilege in my history. It may simply have been a nice ride home, surprising and gratifying for the talk that took place, but not much more. That’s because there probably would have been lots of other events following in its wake; life would have simply gone on, like the flashing scenery, and that ride home would have receded like so many other scenes, falling backward into the past. But life didn’t simply go on; it came to a screeching halt. And as a result, the ride home, even amid its fleetingness, its lack of definition and clarity, has come to loom large in my memory. It has become a monument, a commemorative psychic edifice that I can sometimes enter.

It has become common knowledge that memory, far from reproducing past experience as it was, is constructive and imaginative, maybe even fictive, in its workings. Along these lines, it might therefore be suggested that I myself have created a fiction of sorts surrounding that ride home, transforming what might otherwise have been just another event into something extra important and meaningful—foundational, as I called it. In one sense, this is quite right: without my own imaginative reworking of what happened that fine spring day, without my desire to tell it this way rather than that, it would indeed have been just another event. For all I know, mothers and fathers and their college-age children were all around us, littering the highways, talking with one another, making contact. Isn’t that all we were doing?

Interpretations proliferate at this point. It could be that, in order for me to fend off the grim reality of my father having died without our ever really having the opportunity to make contact, I had to somehow convince myself that we did: after 20 years, something had happened, a breakthrough; boy, was I lucky. In this case, of course, much of what I have told you would deserve to be called illusory, more the product of a wish than a reality. Similarly, perhaps I have merely devised a means, through this yarn, to assuage some of my guilt and shame over the fact that, at the time of his death, I had done decidedly less than my brothers to make him proud. Maybe I had to convince myself that he could see that I was finally getting it together, that I had some promise and potential; to admit that he had seen nothing of the sort would have been too painful, too wasteful. Each of these interpretations presumes that I had somehow foisted meaning onto that car ride, that I had used it as a means of ensuring that there was—or that there appeared to be—some redeeming value to our lives together. I could have chosen any one of a number of things to serve in this role; not unlike the way dreams seem to work, according to Freud at any rate, maybe I just latched on to this particular scene because it somehow allowed me to do what was necessary to carry on with some measure of self-affirmation: I think I can make something of that car ride… .

All of this is possible. But there is another way entirely of understanding what has been done here. The fact is, I don’t really take much solace from that ride home. I’m certainly glad it happened, and in that sense I do feel “lucky.” But that incident, as I suggested a short while ago, is as much about what was, and is, missing as anything else. It is about what was missing from our relationship. There could have been so much—in a way, we proved it in that car—and yet there wasn’t nearly enough. I can still feel the presence of what we missed together. It is also about what is missing now. It’s been many years since that ride home, and in so much of what I have done since that time, particularly those things I might have been able to share with him or that might have made him proud or happy, he is right there, missing. Strictly speaking, it’s not so much him I miss, in the sense of a present being. Rather, I feel the presence of his absence. This in itself might serve to correct the idea that memory deals only with what has actually happened, with “events,” once there, now gone. Memory also deals with what didn’t happen and what couldn’t happen and what will never happen.

There is another way still of fleshing out this idea of the presence of what is missing, and it is here that I turn to the idea of poiesis. It is sometimes said that poetry seeks to make present what is absent in our ordinary, everyday encounters with the world. Or, to put the matter more philosophically, it is a making-present of the world in its absence; it is thus seen to provide a kind of “supplement” to ordinary experience, serving to draw out features of the world that would otherwise go unnoticed. But a kind of puzzle is at work here. If it is assumed that these features go totally unnoticed and that absence is essentially complete, then poetry can be nothing more than the fashioning of illusions, replacing absence with presence. Not unlike what was said earlier regarding that view of memory, which speaks of foisting meanings onto the past, it would have to be considered one more defensive maneuver, one more attempt to fend off meaninglessness. This is possible too: it could be that the meaning of poems, like the meaning of my ride home with my dad, is merely a matter of wishes, that things could be other than the way they are.

But it could also be that absence is not complete and that the world of ordinary experience bears within its absence a certain presence, a limited presence, which the poet, in turn, must try to bring to light. In a sense, you could say that poetry deals with what’s not there and there at the same time. From one angle, it’s about what is absent in presence; it’s about what’s often missing from our ordinary experience of things by virtue of its being “denied” or “threatened by circumstances.” From another angle, it’s about what’s present in absence, the existence of a certain potential, “waiting” to be disclosed. Along the lines being drawn here, there is nothing intrinsically defensive or illusory at all about poems. On the contrary: they may very well serve as vehicles of disclosure and revelation, not so much “giving” meaning to experience as allowing it to emerge.

The same basic thing may be said about hindsight. A short while ago, I flirted with the possibility that the ride home with my dad, ordinary as it was in many ways, might simply be serving as an occasion for me to do some psychological patch-up work. I also acknowledged that, had that ride home not been followed by death, its story might have been told quite differently. Indeed, it may not have been told at all. But what my dad’s death seemed to do was activate the poetic function of memory, such that I would return to that ride home and try to disclose what was there, waiting. The incident itself, as a historical event, was filled with a kind of diffuse, unspecified potential. It could have been played out in a wide variety of different ways, from the most ordinary and unmemorable all the way to the most extraordinary and memorable. It all depends on what follows. The reason the balance has in this case been tipped to the latter is clear enough. If only that ride could have remained in its ordinariness, pleasant and good, father and son, going home for the summer. But it has become filled with an urgency that will always remain. This urgency is not something I put there. Rather, it is something that exists in the very fabric of this story I have been trying to tell. Writing, of this sort, can be strange. Even though I have tried here to “create” something—an image, you could call it, of a significant incident—there is no feeling at all that this image is merely a weakened replica of the real or that it is merely imaginary. In fact, nothing is more real.