Man of letters

Excerpts from Saul Bellow’s lifetime correspondence, including glimpses of Hyde Park and his University colleagues, make a vibrant addition to the writer’s canon.

Introduction By Richard G. Stern, Helen A. Regenstein professor emeritus of English language and literature, Committee on Interdisciplinary Studies in the Humanities, and the College

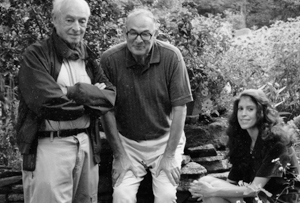

Photograph of Saul Bellow, Richard Stern, and Alane Rollings, courtesy of Janis Bellow. Copyright ©Janis Bellow.

The recent volume, Letters (Viking, 2010) by Saul Bellow, X’39, edited ably by novelist Benjamin Taylor, gives a vivid portrait of Bellow’s life, but anyone who knew him knows that the portrait is but one version of his remarkable life. One can read it and not guess, for instance, that Bellow spent 30 years at the University of Chicago, where he was an active member and sometime chair of the Committee on Social Thought.

Bellow’s letters are varied: some are love notes to various women, a few of whom he married; some describe the familiar early years of a writer’s life, searching for a foothold, searching for money; but the finest letters reveal what most of his friends relished—the wonderful, empathetic ability to enter a troubled existence and to ease it with wit, worldly and otherworldly wisdom.

The ability was the junior partner of the frankest sort of self-display, very critical and often very moving. Many distinguished people have suffered as much, traveled as much, and even been saluted as generously as Bellow, but few, if any, wrote letters as fascinating and moving as he did.

It is partially his style, his famous style, which carries these letters through. For Bellow, every person, every event, and every feeling had a verbal equivalent. His job was in part supplying that equivalent. That his senses were abnormally superior to ours—his hearing was acute, his eyesight exceptional, even his sense of smell was extraordinary—evoked in him unusual equations, so that he frequently spotted your troubles in the pallor of your skin or the color of your irises, decided that your spirits were revealed by the shirt you were wearing; all this makes the letters a kind of textbook of human understanding.

No one else could have written these letters, and they show that the great novelist was also not just a great letter writer but an extraordinary human being. His biography will reveal still another Bellow or two, but it will not contradict these letters; it will at worst include them as a vivid and important part of the writer’s existence.

Bellow’s letter to John U. Nef, X’17, in August 1962 officially began his three-decade association with the University of Chicago.

Dear Professor Nef,

To be invited to join the faculty of the Committee on Social Thought is a great honor. I gladly accept your offer. I am acquainted with the work of the Committee, and I am happy to know that you think I will be able to contribute something to it.

Stern and his wife, the poet Alane Rollings, AB’72, AM’75, were friends of Bellow’s.

Longtime friend Oscar Tarcov heard from Bellow as the author oriented himself to Hyde Park in October 1962.

Dear Oscar—

Having fled defeated from the scene of my own disorganization, I am here, organizing a new chaos. ...

(It’s very curious. I am not interfered with at all. My only work has been my own: Herzog. I should be finished soon. But Chicago is both depressing—dreadful!—and exhilarating. I am waiting to find out why I came here.)

In November 1962, Bellow gave sociologist Edward Shils, X’37—for 45 years a member of the Committee on Social Thought—a report on his haunts as a new arrival to the University.

Dear Edward,

Chicago has opened its arms. I’d like it to stay that way—open arms, not a closed embrace. Susan is very happy here. It would have been unfair and even dangerous to try to keep her on the farm. She has a taste for solitude, like me, but shouldn’t be encouraged. … As for me, I haven’t the smallest complaint to make of Chicago; my life here has been all together pleasant if disordered—but that’s normal with me. I’ve been working very hard, perhaps harder than I should, to finish Herzog. I don’t know whether the poor fellow can stand as much attention as I’ve devoted to him. The Committee has been splendid. I float in and out, have a talk with Father Kim. He tells me why he didn’t become a Communist; I tell him about modern literature. Then I walk on the Midway for the fresh air, and in the stacks for the stale, gaze at the bare shelves in the office and wonder what books [Friedrich von] Hayek kept. I see his cane, like a prop from Sherlock Holmes, hanging on the wall. […] They say he loved mountain climbing. He has left behind a Schnitz-lerian flavor which I very much enjoy. Elsewhere in the city, a certain number of spooks occasionally rise to haunt me. Bitter melancholy—one of my specialties—but sometimes I feel that certain of these old emotions have lost their hold. I realize they no longer have their ancient power. Good idea for a story: the Limbo of terrors which have lost their grip.

By December of ’62 the City Gray began to get a grip on Bellow, as he noted in a subsequent letter to Shils.

Dear Ed—

Susie and I thrive in Chicago, though it has been gloomy. I’m becoming accustomed to the blitzed look of Hyde Park. The vast amount of writing I’m able to do makes me immune to the Stygian darkness.

The death of Bellow’s friend Oscar Tarcov in October 1963 prompted an emotional letter to his son, Nathan Tarcov, now a member of the Committee on Social Thought.

Dear Nathan—

I am deeply, bitterly, sorry that I couldn’t attend your father’s funeral. Oscar and I had an unbroken friendship for thirty years, and since I was sometimes hasty and bad-tempered it was due to him that there were no breaks. I loved him very much, and I know that no son ever lost such a gentle, thoughtful father as you have lost. This is probably not a consoling thing to tell you but I’m sure it expresses what you feel, as well as my belief and feeling. Oscar’s sort of human being is very rare.

My friendship with him and with Isaac Rosenfeld goes back to 1933, when my mother died. I’m sure I brought to these relationships emotions caused by that death. I was seventeen—not much older than you. If I explain this to you, it’s not because I want to talk about myself. What I mean to say is that I have a very special feeling about your situation. I experienced something like it. I hope that you will find—perhaps you have found—such friends as I had on Lemoyne St. in 1933. Not in order to “replace” your father, you never will, but to be the sort of human being he was, one who knows the value of another man. He invested his life in relationships. In making such a choice a man sooner or later realizes that to love others is his answer to inevitable death. ... Perhaps you wondered why I was so attached to him. He never turned me away when I needed him. I hope I never failed him, either.

An October 1974 letter to author Philip Roth, AM’55, described the way Bellow devoured ideas.

Dear Philip—

I was highly entertained by your piece in the New York Review [of Books]. I didn’t quite agree—that’s too much to expect—but I shall slowly think over what you said. My anaconda method. I go into a long digestive stupor.

Bellow feared for the future of the Committee on Social Thought in December 1975, expressing to Shils his pride in and concern for what it might become.

My dear Ed:

[…] The Committee [on Social Thought], though you may not agree, is a very useful thing; it has developed several extraordinary students in recent years. It is no small achievement to turn out PhDs who know how to write English and are at home in several fields—intelligent people who have read Thucydides and Kant and Proust and who are not counterfeits or culture snobs. They will not disgrace the University of Chicago. I’ve met many graduates from other departments of whom the same cannot be said. I myself have not done all that might have been done for the Committee. I had books to write and problems to face, many of these arising from my own unsatisfactory character, but I have nevertheless taken my duties seriously. Now I think it is the University’s turn to be serious and to demonstrate that it considers the Committee to be something more than a celebrity showpiece. The celebrities are beginning to dodder in any case. Unless new appointments are made the Committee will cease to exist. In about five years it’ll be gone.

Congratulating friend and colleague Richard Stern on the birth of his son in October 1977, Bellow mentioned the pride and peril in his own literary fatherhood.

Dear Dick,

Congratulations! Another son. Wordsworth said, “Stern daughter” (“Ode to Duty”) but Gay came through with a boy. Well, a son is what the old folks used to call “a Gan-Eden-schlepper,” a puller-into Paradise. [...]

I’m glad to get your kind words about Herzog. What am I saying?—I swallow them with joy. That Herzog is all right. I hope his luck will last. Though I father interesting characters, it’s in the upbringing that they lose out.

Adapted from Letters by Saul Bellow, edited by Benjamin Taylor (Viking) © 2010. All rights reserved. Brackets added by Taylor; ellipses indicate text omitted by the Magazine.

WRITE THE EDITOR

DISCUSS THIS ARTICLE

E-MAIL THIS ARTICLE

SHARE THIS ARTICLE

RELATED READING

- “Dispatches and Details from a Life in Literature” (The New York Times, November 8, 2010)

- “Saul Bellow, Unbound” (Chicago Tribune, October 22, 2010)

- “The Whole Human Mess: On Saul Bellow” (The Nation, November 23, 2010)

RELATED VIDEO

- “Saul Bellow: The Man, the Writer” (Mind Online, June 1, 2007)