|

|

| The College has big

plans to send more students packing. New study-abroad

and foreign language programs aim to give every

undergrad a chance to trek. |

|

|

| by Charlotte Snow |

|

When she decided to spend her junior year abroad at the London

School of Economics, Heather Lowe, AB’97, had every intention

of applying her lessons stateside. But after studying the European

Union, the Law, Letters, & Society major delayed her graduation

to learn French—in France—so she could accept a Brussels,

Belgium–based European Parliament internship. When the internship

ended this past September, Lowe was asked to stay on as an assistant

to British representative Robert Sturdy.

“Studying abroad has shaped everything I have done since I

stepped off the plane at Heathrow,” says Lowe, via e-mail from

her Brussels post. “Studying at an excellent institution with

people from all over the globe, working in a London shop, living

on a farm in a tiny village in France, meeting many of the dignitaries

I had studied and the authors who wrote about them in Brussels—this

is what education and life is all about, gaining everything you

can from any experience.”

|

Lowe’s is exactly the spirit University administrators hope

new study-abroad and foreign-language initiatives will foster among

students in the College. In the past five years, the number of undergraduates

studying abroad has grown from 46 to more than 180, and Dean of

the College John W. Boyer, AM’69, PhD’75, wants that number

to keep growing. He has recently stepped up efforts to promote his

twin goals of seeing every undergraduate spend at least one quarter

abroad and at least a third of each graduating class attain fluency

in a foreign language.

Given changes in the undergraduate curriculum that will allow students

to take more electives, Boyer expressed confidence in his 1998 annual

report to the College faculty that these goals can be reached. “Perhaps

one of the most important innovations to come forth from the [curricular]

review,” he noted, “was a refocusing and expansion of

our efforts on second-language education and international education,

and, indeed, the conviction that we should view both of these areas

as closely and even inextricably linked. Cross-cultural and second-language

education are intellectual and instructional domains where I personally

believe we can properly and justifiably encourage our students to

use some of their additional free elective space with considerable

profit.”

Boyer has translated this belief into an expanding crop of international

options for College students. Already on the map are programs in

some 20 foreign cities. This academic year the College is launching

more in Toledo, Spain; Rome; Athens, Greece; Dublin, Ireland; Cologne,

Germany; and Tanzania, with plans to debut additional ones in Vienna,

Austria, and Buenos Aires, Argentina. Undergraduates are also heading

to destinations as far afield as China, Siberia, Bosnia, and India

via research fellowships or placements arranged by individual faculty

members.

Back

on campus, a $1.3-million grant from the Mellon Foundation will

help support, over the next five years, the hiring of specialists

in German, Russian, and either Chinese or Japanese; the renovation

of the campus language laboratory; the creation of new language

learning centers in residence halls; and the funding of new language

curriculum grants. By the end of this winter quarter, the College

expects to have completed a nationwide search for a new associate

dean for international and second-language education, who will oversee

all related initiatives on and off campus. And for six weeks this

summer, the College will host an intensive, Middlebury-style residential

language camp in French and Spanish. Back

on campus, a $1.3-million grant from the Mellon Foundation will

help support, over the next five years, the hiring of specialists

in German, Russian, and either Chinese or Japanese; the renovation

of the campus language laboratory; the creation of new language

learning centers in residence halls; and the funding of new language

curriculum grants. By the end of this winter quarter, the College

expects to have completed a nationwide search for a new associate

dean for international and second-language education, who will oversee

all related initiatives on and off campus. And for six weeks this

summer, the College will host an intensive, Middlebury-style residential

language camp in French and Spanish.

“These initiatives will complement what’s being offered

already,” says Nadine Di Vito, director of language programs

in the Department of Romance Languages and Literatures. “We’re

taking steps in the direction of showing students to what extent

language and cultural identity are intimately connected and allowing

them to take advantage of more programs that fit their life aspirations.”

Historically, the College has not been so enthusiastic in promoting

an international flair among its students. Rather, says Lewis Fortner,

associate dean of students in the College and director of undergraduate

foreign & domestic studies, the College has considered its own

soil the best seeding ground. While individual students have always

found ways to travel, work, and study abroad, and have successfully

petitioned for transfer credit upon their return, he says, it was

not until the mid-1980s, under Donald Levine, AB’50, AM’54,

PhD’57, as dean of the College, and Herman Sinaiko, AB’47,

PhD’61, as dean of students, that a formalized approach developed.

In the 1983–84 academic year, the College set up official study-abroad

programs and made financial aid available to all participants. Since

then, Fortner says, support for foreign study has gone “from

lukewarm to moderate to energetic.”

Fortner attributes the invigorated efforts to several factors.

He says the idea of going abroad is more acceptable to today’s

faculty, many more of whom studied abroad as undergraduates themselves.

Practically, a strong economy has helped students pay for travel

overseas, while the business world’s increased emphasis on

global transactions and communications makes the prospect of such

study attractive to more students. For the foreseeable future, Fortner

says, the College will remain intent on preparing students to live

and work in a shrinking world.

“Foreign study is valuable on many levels,” Fortner

explains. “It gives students a larger view of the world and

of America’s place in the world. A serious work or study experience

abroad represents a potent professional or academic credential down

the road. At a deeper level, its benefits are more personal: a wider

understanding of cultures and peoples and of oneself as a citizen

of the world.”

Chicago undergraduates can earn a ticket to this understanding

in several ways. They can cross borders to fulfill their civilization-studies

requirements, work toward a special language certificate, apply

a language-study grant awarded by the College, immerse themselves

in a different culture, or work for an international organization.

Regardless of the route chosen, students typically remain registered

in the College, pay regular College tuition plus a small administrative

fee, retain their eligibility for financial aid, and receive full

credit for their work. All programs—even those requiring competency

in a foreign language—are open to all students in all majors,

though those lasting a year are geared to third- and fourth-years.

They may be organized and staffed by Chicago alone or through partnerships

with foreign universities or with the two higher-education consortiums

to which Chicago belongs—the Associated Colleges of the Midwest

and the Committee on Institutional Cooperation.

Undergraduates who have already ventured out of Hyde Park suggest

that foreign-study opportunities should receive greater publicity

on campus and note that not all University departments make it easy

for students to complete their major requirements if they study

overseas. They also urge alumni living abroad to provide a support

network for students. Lowe’s internship in Brussels, for example,

was organized by Stephanie Rada-Zocco, AB’88, a former assistant

at the European Parliament. But overall, most participants seem

to agree that the experience can be life-changing.

“The benefits you receive cannot possibly be outweighed by

considerations like fulfilling requirements or becoming out of touch

with the U of C environment,” says third-year art-history concentrator

Claire Orenduff, now in Paris for the year. “It does take more

work to let everyone know that you’re still out there, and

to organize things at Chicago from across the ocean, but you can

stay in touch if you make the effort. I have grown in ways that

I wouldn’t have been able to conceptualize before coming here.”

Perhaps the College’s most innovative approach to grooming

cosmopolitan students has been its creation of a civilization-studies

sequence compressed into one quarter that allows undergraduates

to fulfill their Common Core requirements and at the same time experience

a foreign culture. The courses are taught abroad by Chicago faculty

and are open only to Chicago students.

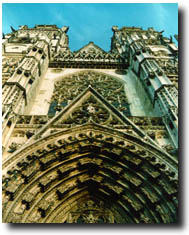

Philippe Desan, master of the humanities collegiate division, says

he came up with the idea as a way of teaching the civilization sequences

in context. He began in winter quarter 1997 by exporting Chicago

faculty members and about 25 undergraduates to Barcelona, Spain.

Desan then organized a similar course in Tours, France, which first

accepted students in spring 1998. This past autumn saw the addition

of Rome; an Athens venture will begin this spring. In the 1999–2000

academic year, students will have the option of Vienna and Buenos

Aires, and, in later years, Africa, the Middle East, and other South

American sites. Though the courses share a great deal with those

taught back in Chicago, Desan explains, “we also try to use

the culture at hand.” For example, in Tours the Renaissance

is emphasized because the city is located at the heart of a rich

artistic and cultural tradition that peaked during the 16th century.

“The greatest challenge is to ensure the programs’ academic

rigor,” says Desan. “We certainly want the students to

experience a different culture, but we also want to keep the same

intellectual standards. The courses taught are real U of C courses,

and my job has been to make certain we do not water down the academic

side.”

Chicago faculty have found the experience of teaching their life’s

work in its birthplace intense. Charles Cohen, professor of art

history and chair of the Committee on Visual Arts, taught in Rome

this past autumn. “It was almost sublime for me to be able

to view the works of art, walk the streets, and experience the piazzas

laid out in the Renaissance and Baroque with Chicago students,”

Cohen says. He recalls how he and his students spent a day in the

classroom discussing the rise of St. Peter’s Cathedral over

300 years, and then spent the next day on site experiencing its

space and interpreting its papal tombs.

“This is as complete a way as I can imagine to be introduced

to these central monuments of the Western tradition, though the

experience can be difficult and messy as well,” Cohen says.

“Churches can be cold and dark, works of art are not always

placed for ideal viewing, and half of Rome seemed to be under scaffolding.

But all this, along with aching feet and grumbling stomachs, is

often part of the experience, and I was perfectly happy to have

our students understand the difference between casual tourism and

really digging into the real stuff.”

Emily C. Chang, a third-year English concentrator, participated

in the Rome quarter and would definitely recommend the experience.

She enjoyed weekend trips to the island of Capri, Florence, Switzerland,

Venice, and Milan, and found the workload “just about the same

as a U of C class, maybe a little less.” Learning this way,

she says, “you realize that there’s so much more to life

than studying at the Reg.”

Other faculty and students will be packing soon for the spring

quarter in Athens. Christopher Faraone, chair of the Department

of Classical Languages and Literatures, will teach a course on the

history and material culture of Athens from Mycenaean to Byzantine

times. Faraone says his own experiences as an undergraduate traveling

in Egypt, Israel, and Greece “helped create in me a lifelong

interest in ancient history and archaeology.” He plans to arrange

field trips to archaeological sites or museums at least three times

a week and to require students to give on-site presentations on

sculptures, vase paintings, and monuments. He also hopes to set

up a Web site where students can post photos and notes so that family

and friends can follow their progress.

“I think the students will come away with a tremendous understanding

of how accidental features of topography, natural resources, and

climate intersect with history in very important ways,” he

predicts, noting that Athens’ small size allowed its citizens

to invent and practice direct democracy.

Gretchen Moeser, a third-year geophysical sciences major, has

signed on for the trip. Though nervous that she cannot speak “a

word of Greek,” she looks forward to experiencing a different

lifestyle and environment: “I’ve read pieces by Plato

and Socrates and about ancient Greece, but it will be interesting

to learn more about modern Greece and how Greece is still affected

by its history.”

Besides civilization studies, the gift of gab has provided many

students with a passport overseas. The foreign language proficiency

certificate, adopted in 1996, helps spur students to talk their

way abroad. The certificate requires at least two years of study

and was awarded to 47 undergraduates for the first time last year.

The certificates—noted on College transcripts—recognize

those students who have not concentrated in a foreign language but

yet have attained proficiency. The first group of recipients studied

French, German, Italian, or Spanish. They took advanced courses

and had to pass oral and written examinations each quarter, including

a formal competency exam adapted from the Georgetown University

School of Foreign Service. Each also studied for at least one quarter

abroad, living with host families while enrolled in an intensive

language class.

As another incentive, last summer the College began a new foreign

language acquisition grant program, which sent 25 undergraduates

to language institutes all over the world, where they studied Breton,

Chinese, Czech, French, Gaelic, German, Hindi, Italian, Korean,

Polish, Russian, or Spanish. The College plans to award 50 FLAG

grants this summer, 100 in 2000, and at least 200 beginning in 2001.

Additional overseas language learning takes place in affiliation

with foreign universities—including the University of Paris,

the University of Bologna, Freie Universität in Berlin, and

the University of Seville—where undergraduates can pursue intermediate

and advanced studies.

For Orenduff, one of her best memories in Paris so far is of being

invited by a friend’s neighbors to tea and managing to converse

with them in French. “Anytime I am forced to communicate in

French and am able to get my point across eventually, it feels great,”

she says. “There are actually times I find myself at a loss

to express an idea or concept in English that I have recently learned

to incorporate into my French vocabulary. You’re forced to

take a more severe, critical look at expression through words.”

But students don’t have to study civilizations or be bilingual

to see the world. They can enroll in classes at affiliated British

and Irish universities. Third-year chemistry concentrator Douglas

Higgins is now at the University of Edinburgh, where he has taken

up Scottish country dancing and “talked about and debated topics

ranging from politics to uses of sodium bicarbonate and its differences

from baking powder.” Still other options emphasize fieldwork

and research. This past fall, anthropology professor Russell Tuttle

directed the ACM’s semester-long Tanzania program. Five College

students, along with about 10 others, divided their time between

classroom work at the University of Dar es Salaam and fieldwork

in the northern region of Tanzania. They studied Swahili, human

evolution, and the ecology of the Serengeti Plain; explored independent

research topics; and lived in tent camps.

For students who want off the beaten paths, the College can arrange

more individually tailored experiences. In 1994, the College awarded

its first international traveling research fellowships to students

who used the money to study in China and Siberia. Last summer, 11

students worked for national and international human-rights organizations

through the Chicago Initiative on Human Rights. They included Elizabeth

M. Evenson, a fourth-year dual concentrator in public policy and

political science, who helped Physicians for Human Rights identify

war dead in Tuzla, Bosnia. After completing a two-year Marshall

scholarship studying international human rights law at the University

of Nottingham, she plans to attend law school.

“My time in Bosnia was incredibly eye-opening and will permanently

color my world view,” she says. “Having never seen war

before, when I now hear news accounts about conflict in any part

of the world, images of destroyed buildings and massive cemeteries

in Sarajevo, with grave markers clustered so thick you can’t

tell where one ends and the next begins, flood my mind. I don’t

think that I can ever again be indifferent to allegations of human-rights

violations and abuses in any part of the world now that I have faces,

names, and so many personal stories to go along with the headlines.”

The human-rights initiative also placed third-year philosophy

concentrator John Rory Eastburg in Bombay with VOICE, a grassroots

organization that teaches reading, math, and job skills to children

who work on the city’s train platforms. Eastburg, the president

of Chicago’s chapter of Amnesty International, was impressed

by how the efforts of just 20 staffers could benefit the lives of

as many as 400 children. The experience further convinced him that

economic and social rights “are absolutely necessary to the

concept of humanity, and that they are necessary for the real fulfillment

of more traditional civil and political rights.”

Spoken like a true citizen of the world.

|