|

Lewis has no wish to raise Cobb to genius status. But he would

like more people to know about the man he describes as one of the

leaders of the Chicago school, “a group of Midwestern architects

who made great developments in structure and design.” And he

has been given the opportunity to do just that. Last year, some

40 years after he wrote his master’s thesis on Cobb’s

campus oeuvre, Lewis was commissioned by the Richard H. Driehaus

Foundation to produce a book on Cobb’s other buildings.

|

While the top floor of the Durand

Institute at Lake Forest College, according to Lewis, “has

obviously been much mauled,” the wood and the grand space

remain “Cobb at his best.” Lewis also notes similarities

to the architect’s work at the Yerkes Observatory, including

the way that Cobb used wood to emphasize the strong, graceful

lines of the room’s high-pitched ceiling.

|

Driehaus, the CEO of Driehaus Capital Management, Inc., first

became interested in Cobb when he bought the Cable House, a down-at-the-heels

mansion at 25 East Erie Street, built by Cobb and Frost in 1886

for Ransom R. Cable, the president of the Chicago, Rock Island and

Pacific Railway Company. While changing the building’s interior

to accommodate a contemporary lifestyle, Driehaus carefully restored

the exterior to its original grandeur. He asked the foundation’s

executive director, Sonia K. (“Sunny”) Fischer, AM’82,

to see if she could find more information on Cobb. Tracking down

Lewis’s thesis, Fischer called to ask him for a copy.

|

Not all of Cobb’s work was

completely successful, as this side view of the Durand Institute

demonstrates. Though the rectangular brace of windows provides

wonderful illumination of the interior space, it’s out

of scale with the two sets of windows below. “It would

be very beautiful if you could ignore the bottom two floors,”

laments Lewis. “Richardson would have done better.”

|

The attorney readily assented—on the condition that he be

given an insider’s tour of the restored Cable House. When Lewis

met Driehaus, the proud owner asked if he knew anyone who could

write a book on Cobb. The reply came quickly: If anyone did such

a book, “it ought to be me.”

Driehaus agreed, supplying funds to have Hyde Park photographer

Patricia Evans provide visual documentation of Cobb’s buildings

and to hire Lewis a research assistant—Ronn M. Daniel, an Illinois

Institute of Technology–trained architect and a U of C graduate

student in the history of culture. Soon after, Lewis and Daniel

began to track down material, visiting buildings in and around Chicago.

With 85 percent of the research complete, this summer Lewis was

about to embark on the book’s first draft. He hopes the project—which

incorporates his thesis but includes a great deal of new material—will

be done within a year.

Gathering information on Cobb and his non–U of C buildings

hasn’t been easy. “His papers are all gone,” Lewis

notes, and so the task has been one of reconstruction.

|

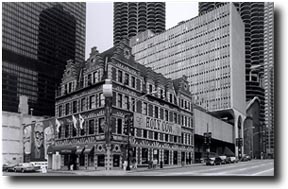

Like the current occupant of the

building at the southeast corner of North Dearborn and West

Kinzie Streets—Harry Caray’s Restaurant—Cobb’s

original client, a fuel oil and paint company, wanted a structure

that stood out. Cobb achieved that, using decorative details

from the Dutch Renaissance (patterned brick and stone and

stepped gables) for the warehouse cum office building.

|

Although it’s been especially hard to trace Cobb’s work

after he ended his connection with the University, accounts of Cobb’s

early years aren’t much more detailed. Born in Massachusetts

in 1859, he was one of the earliest students to complete an architecture

course—the nation’s first such formal course—offered

by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. A few months after

his 1880 graduation, he made the obligatory trip to Europe to see

the great buildings he had studied. Upon his return, he worked for

a few months at the Boston firm of Peabody and Stearns before heading

west in 1881 to Chicago, where he soon flourished.

Continued...

|