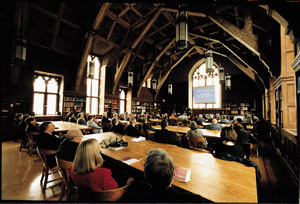

Chicago:

Campus of the Big Ideas

>> The

launch of The Chicago Initiative-the University's five-year, $2

billion fund-raising effort-was marked by an April 12 event that

focused on Chicago's intellectual initiatives.

|

5

|

Clones,

genes, and stem cells: can we find the path to the greatest

good? |

The quick response to this session's query-at least judging from

the panelists' takes on the topic-is, how can we know until we're

allowed to try?

Not

that a snappy rejoinder resolves it. Indeed the discussion raised

as many questions as it answered. Stem-cell research, noted Lainie

Ross, associate professor in pediatrics and the MacLean Center

for Clinical Medical Ethics, is still "at the real embryonic

stage-pun intended."

|

|

|

A

discussion of stem-cell research raised "Why not?"

questions.

|

For

the nonscientists in the audience, she reviewed the basic science

involved in "harvesting" stem cells, which can generate

and renew tissue and are present in every organ, including those

in the adult body. "The source matters," said Ross.

Embryonic stem cells can be procured from the inner cell mass

of a "blastocyst," an early-stage embryo, or from an

aborted fetus. Stem cells can also be obtained from the placenta,

and adult stem cells can be procured from many tissues in the

human adult patient. The more mature the organism from which the

stem cells are derived, the less malleable they are and the more

likely to induce an immune response if placed in another person's

body. Nevertheless, adult stem cells are much more "plastic"-and

hold more promise-than scientists once thought, but they're neither

as ubiquitous nor as "pluripotent" as embryonic stem

cells, which can grow into any kind of cell.

For

those who find it morally repugnant to start a human life only

to end it at blastocyst stage for research, the controversy is

a cut-and-dried issue: federal funding for research with embryos

should be banned. The National Academy of Science disagrees, supporting

embryonic stem-cell research for therapeutic purposes. Leaving

his scientist-colleagues to argue for therapeutic cloning, Robert

Richards, PhD'78, professor in history, philosophy, psychology,

and the College, instead questioned whether reproductive cloning

is such a bad thing after all: "Physicians already intervene

and thwart nature," parents already "design" their

babies by choosing mates with good looks and smarts, and "repugnance,"

he said, is an unreliable moral guide. "It's doubtful reproductive

cloning would be undertaken except for fertility reasons,"

and after much thought his view is, "Why not?"

Why

not? was the question of the afternoon. As a silver-haired gentleman

in the audience asked, "Why do legislators have to be involved

in scientific research at all?" The answer is economics.

Panel moderator Janet Davison Rowley, PhB'45, SB'46, MD'48, the

Blum-Riese distinguished service professor in medicine, reminded

attendees that no U.S. scientist can now get federal funding to

learn how embryonic stem cells "do what they do." She

warned of an impending "brain drain," as researchers

leave the U.S. for countries more open to their work. And Ross

noted the irony in scientists scurrying to private funding sources:

"Doesn't it make more sense to keep controversial research

in the public sphere, where you can maintain higher levels of

oversight?"

One

positive result of the controversy, noted Olufunmilayo Olopade,

an associate professor in medicine who studies the genetics of

cancer, is that researchers no longer assume they'll receive funding.

"We have to be honest with Congress and educate the public.

It's not enough to say we need this funding so we can cure every

disease imaginable. We're a long way from that." Whether

they'll be allowed to try is a question still to be answered.

-S.A.S.

1.

In

the beginning: what do our origins tell us about ourselves?

2.

Homo sapiens: are

we really rational creatures?

3.

Integrating the

physical and biological sciences: what lies ahead?

4.

Money,

services, or laws: how do we improve lives?

5.

Clones, genes, and

stem cells: can we find the path to the greatest good?

6.

How will technology change

the way we work and live?

7.

Why do we dig up

the past?

8.

Art for art's sake?

9.

In the realm of

the senses: how do we understand what we see, hear, feel, smell,

and taste?

10.

Can we protect

civil liberties in wartime?

CHICAGO

INITIATIVE GOALS

![]()