Chicago:

Campus of the Big Ideas

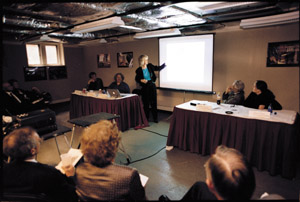

>> The

launch of The Chicago Initiative-the University's five-year, $2

billion fund-raising effort-was marked by an April 12 event that

focused on Chicago's intellectual initiatives.

|

9

|

In

the realm of the senses: how do we understand what we see,

hear, feel, smell, and taste? |

The

goal, said James Chandler, AM'72, PhD'78, the Barbara E. &

Richard J. Franke professor in English and director of Chicago's

Franke Institute for the Humanities, was to "try to make

sense of the senses." To that end, four scholars tackled

sound, smell, touch, and sight. (Taste, Chandler joked, would

have to wait for the post-symposia reception.)

|

|

|

Martha McClintock discusses chemosignals and pheromones:

smell.

|

We

are what we sense, suggested William Wimsatt, professor in philosophy.

Or are we? In the 1974 paper, "What Is It Like to Be a Bat?",

philosopher Thomas Nagel argued that a bat's conscious experience-a

world perceived through echoes of high-frequency sound signals-is

so different from the conscious experience of humans that we can

never fully imagine it. Yet, Wimsatt noted, human technology and

instrumentation "is very productively seen as an extension

of our senses," allowing us to experience the world in ways

that our physiology doesn't-in ways, for example, that mimic a

bat's sense of things.

Are

we culturally biased against certain senses? Take smell. "I

want to champion the causes of odor and communication," said

Martha McClintock, the David Lee Shillinglaw distinguished service

professor in psychology and director of the Institute for Mind

and Biology. In her research on chemosignals and pheromones, McClintock

said, she has tried to show how smell can "influence humans

positively." Most recently her team has demonstrated that

women prefer the odor of males to whom they are genetically similar-but

not identical-over those who are either nearly identical or completely

unfamiliar, work that may help explain how certain genes influence

mating choice.

Moving

from 21st-century experiments to 19th-century medical history,

Alison Winter, AB'87, associate professor in history, began with

a paradox: although nitrous oxide or "laughing gas"

was well known by the 1790s it wasn't until the mid-1840s that

the anesthesia began to be widely used to blunt the pain of the

surgeon's knife. Winter's tale of mesmerists and medicine argued

that anesthesia's adoption "was not a medical watershed as

much as a sea change in sensibility," the result of a change

in how humans felt about pain, "a different set of expectations

of what the senses could do and what we could do to the senses."

A

changing perception of the power of the senses was also the theme

limned by Tom Gunning, professor in art history and the Committee

on Cinema & Media Studies. The infancy of American cinema,

he said, coincided with a "deep-rooted suspicion of the visual

senses," a suspicion that prompted a 1915 Supreme Court censorship

ruling to inveigh against film as "capable of evil,"

especially where "susceptible publics"-women, children,

and the poor-were concerned. The Supreme Court's argument, Gunning

noted, implied that the new medium was exempt from the First Amendment

because it was more powerful than print and "the visual

might somehow overwhelm the verbal."

That

story from moving-picture days may seem quaint, but Gunning pointed

to a contemporary moral, arguing that "training the senses,

realizing their unique forms of knowledge," remains an important

task in the 21st century.

-M.R.Y.

1.

In

the beginning: what do our origins tell us about ourselves?

2.

Homo sapiens: are

we really rational creatures?

3.

Integrating the

physical and biological sciences: what lies ahead?

4.

Money,

services, or laws: how do we improve lives?

5.

Clones, genes, and

stem cells: can we find the path to the greatest good?

6.

How will technology change

the way we work and live?

7.

Why do we dig up

the past?

8.

Art for art's sake?

9.

In the realm of

the senses: how do we understand what we see, hear, feel, smell,

and taste?

10.

Can we protect

civil liberties in wartime?

CHICAGO

INITIATIVE GOALS

![]()