Anatomy classic

By Jake Grubman, ’11

Image from Stanton A. Friedberg, MD, Rare Book Collection of Rush University Medical Center at the University of Chicago

In December 2009 the University Library announced it was buying 3,500 rare books from Rush University Medical Center, a purchase made possible by the bequest of late Oriental Institute professor Erica Reiner, PhD’55. Among the collection, dating from 1500 to the mid-1900s: editions of Hippocrates and Galen’s writings, a volume on botanical medicine, and the first work on plastic surgery.

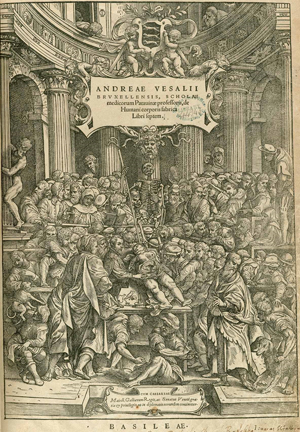

Robert Richards, PhD’78, the Morris Fishbein professor of the history of science and medicine, took notice of one title: the first edition of Andreas Vesalius’s De Humani Corporis Fabrica (On the Fabric of the Human Body), a seminal work of Renaissance-era anatomical illustrations. At right is the book’s title page, showing Vesalius dissecting a female cadaver.

The newly acquired Fabrica is the University’s second copy, and the marginalia of both provide insight into the books’ use. “I’m interested in how books were read in the Renaissance,” Richards says. “There are commonalities with the way students read today. It helps us know what was important.”

Printed in 1543, the Fabrica was remarkable both as a study and as a physical book. Its visual accuracy and complexity were unmatched in that period, and it would have been beyond the budgets of ordinary physicians. Instead, printed under Vesalius’s close watch, it was made for wealthy connoisseurs and elite physicians.

Originally 43 centimeters tall (a 1581 rebinding shortened the book), the Fabrica built on Galen’s medical studies, emphasizing contact with the human body to understand anatomy. Sometimes Vesalius used executed criminals as models. “If you look at the figures in the Vesalius and compare them with contemporary textbooks,” Richards says, “they’re quite clearly of organic material.”

With 420 diagrams—usually thought to be the work of Italian painter Titian’s studio—Vesalius corrected some of Galen’s conclusions: depicting blood vessels, for example, Vesalius noted their origin in the heart, not the liver. Still, he perpetuated some mistakes, relying on animal specimens to diagram parts of the human body—a cow’s eye stood in for a human one. “It’s interesting,” Richards says, “the ways in which even the most attentive scientist will have his vision shaped by anterior assumptions.”