|

|

|||||||||

|

1913 The June issue was devoted to the 37 original faculty members still teaching at Chicago two decades later. Among the group was a lone female: Dean of Women Marion Talbot. Born in Switzerland in 1858, Talbot earned degrees from Boston University and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Previously an instructor at Wellesley, she came to Chicago as both the dean of women and an assistant professor of sanitary science; in 1894 she became a full professor of household administration. As dean she always lived in one of the women’s dormitories: the “Beatrice,” Snell, Kelly, or Green.

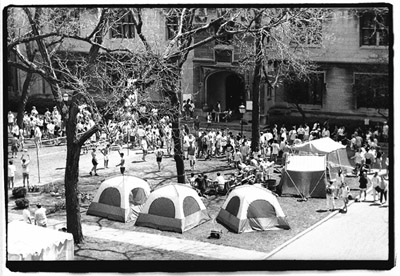

1953 In an excerpt from his lecture series “Hazards to Education in the United States,” Robert Maynard Hutchins imagined the ideal educational institution. In this “University of Utopia” professors would be free to elect their colleagues and determine their programs of study but would do so under careful scrutiny from the trustees, whose job would be not to operate but to criticize the university. Most important, all ideas—no matter how controversial—would be allowed expression. As Hutchins argued, “A university that is not controversial is not a university. A civilization in which there is not a continuous controversy about important issues, speculative and practical, is on the way to totalitarianism and death.” 1978 The summer issue included “The Academic Year in Review.” College tuition in 1977–78 was $4,095, and the University’s student population hovered near 7,850. Of those students, 510 lived in the “Shoreland Hotel,” which they shared with 40 permanent residents. The year was enlivened by a few celebrity visitors to campus, including Prince Charles in October and comedienne Joan Rivers in April. In December the acting president of Yale, Hanna Holborn Gray, was elected Chicago’s president. In May the College received more than 2,700 applications—the largest number since the late 1940s. On a less hopeful note, in June the 13-year Campaign for Chicago concluded $111.5 million short of its original $280 million goal. 1993 What many College students considered the biggest party of the year was canceled. “Sleepout”—the tradition of camping out on the main quadrangle over Mother’s Day weekend to secure an early registration time—was abolished. The change was made both to implement a system assigning registration slots according to class year and to alleviate safety concerns. Not only had drinking become a major component of Sleepout, but the undergraduates’ large tents and stakes damaged the quad’s sprinkler systems and grass. In an effort to get College administrators to change their minds before Mother’s Day, some students organized a protest. The demonstration at the flagpole drew about 100 students, or less than one-tenth of the 1,000-plus who slept out in 1992, Sleepout’s last stand. —D.G.R.

|

|

Contact

|