|

|

| Bursting at the seams That’s how Chicago arts faculty describe their programs. A new Center for Creative and Performing Arts could alleviate the overflow—and develop a model for nurturing the arts at a research institution.

Imagine an MFA student sharing a paint shop with undergraduates designing theater sets, showing them how to create a more realistic backdrop. Or, in a shared computer lab, musicians composing a score for a film student’s short movie. Or sculptors and photographers brainstorming ideas for an installation exhibit over coffee. Such collaboration pervades the University’s vision for a new Center for the Creative and Performing Arts, where Chicago’s interdisciplinary thinking can infuse artistic endeavors. The facility, planned for five to ten years from now, or whenever the University raises the $53 million (in 2003 dollars) needed for Phase I of the project, is still in the conceptual stage. But the idea of a center that encourages collaboration, where the arts are not only housed under the same roof but also share rooms—a carpentry, metal, paint, and costume shop; a lounge; a café; exhibit and theater space—has been germinating for several years. In fall 2000 then-provost Geoffrey Stone, JD’71, convened a faculty committee and an advisory group of faculty, students, and staff to study the arts on campus. Stone, the Harry Kalven Jr. distinguished service professor in the Law School and the College, began the project, he says, because of growing faculty and student interest in arts activities as well as “the absence of a clear sense of how these activities fit into the University’s larger mission.” A year later the committee released its recommendations, calling for both an Arts Planning Council, which formed shortly thereafter, and a new facility for “visual arts, music practice and rehearsal, and theater and performance.” The interdisciplinary focus, “the idea of bringing together people in the arts, that the whole would be bigger than the sum of its parts,” Stone says, emerged early on. Other colleges and universities—Chicago’s arts center steering committee visited Grinnell, Valparaiso, and Ohio State—have modern multidisciplinary arts facilities, where departments share the same building but have their own wings or sections. Chicago’s more cohesive plan (New York architects Hardy Holzman Pfeiffer Associates have designed a 182,000-square-foot conceptual blueprint, but bids for an actual building have not yet been placed), to provide departments their own areas plus some common space, appears to be a novel approach. The center’s steering committee particularly favors the plan’s “arts alley” featuring a café, lounge, and perhaps a glass roof. In such an area “students and faculty could gather informally,” an April 2004 report says, “and serendipitous transfers of ideas and insights could occur.” A shared shop would both reduce the square footage needed for the center and foster previously difficult or unimagined alliances. “Smart” classrooms, containing high-tech audio-visual and computer equipment, would double as rehearsal space. Seminar and lecture/screening rooms, a computer lab, and shared faculty offices would be used by multiple departments. As Humanities Dean Janel Mueller, who cochairs the steering committee with Associate Provost Mary Harvey, PhD’87, puts it, “We can create something both defining of the University of Chicago and on the forefront of arts development.” Mueller’s personal inspiration for an “arts village,” she says, comes from painter Lyonel Feininger (1871–1956), whose cubist townscapes of interwoven buildings and pedestrians evoke “a sense of a cluster of spaces, almost organically fused together,” portraying “solidity, intimacy, connectedness.” The time for such a village seems right: an integrated approach echoes the current art trend of mixing media. “Opera used to be where a number of the arts converged,” notes Mueller, the William Rainey Harper distinguished service professor in the College and a professor of English language & literature. Now, she says, the convergence occurs in installation and performance pieces. Committee member William Michel, AB’92, the University’s assistant vice president for student life, agrees. “The really interesting art happening today and into the future,” says Michel, who formerly directed University Theater, “is art that encompasses many different media at the same time, whether that be dance and film or theater and visual arts.”

Mixing media at Chicago, however, requires significant

effort. The disciplines are not only separated from each other but

also divided among themselves. Music, for one, lives mostly at Fulton

Hall, which holds professors’ offices, student practice rooms,

and a 100-seat concert hall. But performances for larger audiences

or needing a bigger stage take place across the quads at the 1,000-seat

Mandel Hall. University Theater (UT), meanwhile, is stationed on

the Reynolds Club’s third floor, but students rehearse in

Cobb and Bartlett, and UT’s shop for constructing sets and

costumes is in a former print shop at 50th Street and Cornell Avenue.

The Film Studies Center, where film research and screenings take

place, has Cobb Hall quarters, but most of the Committee on Cinema

and Media Studies faculty have offices in Gates-Blake. Meanwhile,

the Committee on the Visual Arts (COVA) resides at Midway Studios,

in the campus’s most southwest corner.

Midway Studios itself, though beloved for its sense of character and historical importance, is “falling apart,” says assistant professor Alison Ruttan, who teaches painting, drawing, and digital media. Once a communal haven for sculptor Lorado Taft, where he and other stone carvers lived, worked, ate, and partied, the building was always makeshift. In the 1920s and ’30s Taft had a carriage house, a three-story brick house, and a half-dozen other buildings literally picked up, dropped, and attached to each other at Ingleside Avenue and 60th Street. The resulting maze of white paint–flecked bedrooms-turned-studios, staircases to nowhere, and upstairs balconies that once faced outdoors was designated a national landmark in 1966. As campus arts grew, in 1977 the Women’s Board donated funds for a 2,150-square-foot addition, a two-story painting studio. In 2000–01 the University spent $300,000 to drive out the rats, mend the leaking roof, and secure the doors to the outside. The next year an ID-card-swipe entry was installed; before that students working after-hours had to call University police from a corner emergency phone to unlock the door. More recently new studios, a new classroom, and three editing and computer labs were added. Despite the improvements, the original structure—never meant for photography and painting, much less for today’s media and digital arts—needs a new roof, better air circulation, and updated technology. While Midway Studios has one black-and-white graduate-student darkroom, the color and undergraduate darkrooms are in Cobb, where the constant spilling of processing fluids has crumbled and softened the tile floors, and the few enlargers don’t meet the demand. By building a new arts center adjacent to Midway Studios’ landmark portions (the newer sections would be torn down), the University would be able to fix such problems, and a modern structure would accommodate COVA and other campus arts. Those other departments need updating too. More than 650 students take part in University Theater each year, producing 35 shows. Undergraduates can now concentrate in theater and performance studies, and the 30 related courses continue to fill up quickly. Student productions, held in either the 100–150-seat first-floor Reynolds Club theater or the 137-seat third-floor space, “sell out in ten minutes,” says UT director Heidi Coleman, “because the audience is so small.” Converted from a lounge to a black-box theater, the first-floor space has a low ceiling, preventing students from experimenting with lighting angles. Directors and designers should begin with a blank slate—“like a lab,” Coleman says—to “decide the actor-audience relationship, think about space and design, lighting, set, costumes.” To rehearse, students invade more than ten Cobb Hall classrooms every night, spending a half hour dragging chairs and desks out of the way (and later replacing them), performing in space one-third the usual stage size. The Cornell Avenue building that holds the shop, meanwhile, will be leased to the Hyde Park Arts Center, likely by summer 2005, and the University is still working to find a large enough interim replacement. In Fulton Hall the 100 music graduate students, 550 ensemble players, and many extracurricular vocal groups, bands, and chamber players need more practice rooms. At 3:15 on an April Thursday afternoon, some students play fluid classical piano, others practice a Broadway duet on scarred uprights or baby grands. Six of the ten available rooms are filled. “Most universities would have 30 to 40” such spaces, says Barbara Schubert, X’79, senior lecturer in music and director of performer programs. The rooms, meanwhile, aren’t meant to store instruments. Instead of the 68 degrees and high humidity ideal for piano maintenance, the building’s steam heat dries out the instruments, and when it gets too hot players open the windows, causing destructive temperature changes. “We’ve replaced a lot of our pianos” earlier than should be necessary, Schubert says. Although the Fulton Recital Hall holds 100 seats and Mandel Hall holds 1,000, the ideal setting for many student performances, she says, is 300–350 seats. The Fulton stage and audience are inadequate for chamber music and jazz X-tets, but in Mandel Hall—which has no air conditioning—players and audience get swallowed by the huge space. Film too needs better facilities and more space. About 30 undergraduates and 30 graduate students earn degrees from the Committee on Cinema and Media Studies (CMS) each year. As the committee and the Film Studies Center hold more public events, community members can’t easily find the center on Cobb’s third floor, and, when they do, the 125–150-seat theater is often SRO. During a recent Andy Warhol film series, including a rare double-screen projection of Chelsea Girls, “I had to turn people away,” says Julia Gibbs, assistant director of the Film Studies Center. About twice as many people showed up as the theater could fit. Film faculty, meanwhile, prefer not to screen videos or DVDs but films—as “they were meant to be shown,” Gibbs notes—but the center has no appropriate place to store sensitive negatives. A cold, dry vault is needed for teaching films and to begin an archival collection. The current vault in Cobb has already run out of shelf space, and humidity easily seeps in. Last July 4, says CMS chair James Lastra, campus construction crews accidentally turned a valve that heated the vault to over 100 degrees—double the ideal 50.

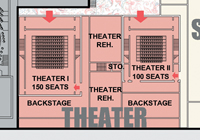

The new center won’t fulfill everyone’s wish list. Sculptor Herbert George’s undergraduate students, strewn about Midway Studios’ grassy courtyard a few minutes before class one April afternoon, sporting protective goggles as they pound hammers and chisels into gray alabaster or limestone, tick off Chicago’s material-arts deficiencies. “How about glass blowing? Or jewelry making? Or metal working?” suggests second-year Kathryn Tabb, garnering “yeah”s and nods from the others. While the first two requests didn’t make the new plans, metal-working tools did. “And where’s the pottery wheel? I’ve heard Harvard has pottery wheels in the dorms.” Ceramics isn’t on the list—it’s one of those tough choices the committee had to make, Michel says. But he hopes to find a pottery wheel elsewhere on campus for student use. (For the record, Harvard’s Quincy House and possibly another dorm, according to housing officials there, do offer pottery wheels.) Other departments see both pluses and minuses in the center’s blueprint. While Schubert is pleased that the plans contain about 20 temperature-controlled music practice rooms and rehearsal and office space, she worries that a 350-seat theater isn’t planned until Phase II of the project—a $33.5 million (in 2003 dollars) addition after Phase I is completed—and that instead of scrambling between two campus locations, she’ll now travel among three. Music, she frets, isn’t a big enough focus. “If the idea is that you’re bumping into people over coffee,” she says, “if you’re not there, you’re not part of the collaboration.” But overall, she stresses, the plan “presents a good step forward” for campus arts. Coleman is thrilled to see two correctly built

theaters (one seating 100, another seating 150) with appropriate

backstage and green rooms, more rehearsal and classroom space, scenery

and costume storage, and a new shop. But she too now has one more

work location, and she worries about sharing shop space. Undergraduates

building a set “play loud music, yell back and forth,”

she says. “The way a painter uses an open tool space is different

than the way theater uses it,” George agrees, and a graduate-student

sculptor might not prefer such a chaotic environment. Film will

still be based in Cobb, but, Gibbs says, “We got what we asked

for”: more screening space in a better public location and

the temperature-controlled film vault. Visual arts, meanwhile, will

get more studio, sculpture, painting, printmaking, photography,

projection, and exhibit space. A main point of the center, committee members say, is to boost the spectrum, caché, and knowledge of Chicago’s arts scene. Rather than promote “the traditional idea that arts are for recreational purposes or for self-exploration beyond one’s main studies,” Mueller says, Chicago should foster art as an end in itself. “Learning the thought process for painting and drawing and theater and music can enrich your life outside of your studies,” Michel adds, “but also provide you with a full skill set that complements what happens in the science labs and math class.” The heightened attention on the arts will benefit students. “The work that students do here is incredible,” Coleman says, “but they don’t know that. They’re proud and very serious, but they don’t know that it matters to anyone outside of here. Having a space designed for them shows respect for their work and encourages them to go further. They’re starting to realize that the University cares about the arts as much as they do, that it’s legitimate.” Adhering to a two-year-old University policy, construction on the Center for Creative and Performing Arts won’t begin until 85 percent of the funds are raised. But once built, like Midway Studios it will be a place for creativity, where spilling paint is OK, where students perform in the hallways. “It’s not pristine,” Michel says. “The energy of this building should come from people sitting in the lobby or carrying flats [for theater sets] through the hallway.” Crouching in Midway Studios’ courtyard, chipping away at his alabaster sculpture, first-year biology major Kyle Guzik has grand visions for Chicago’s arts scene. “This college has the finest biology, math, and economics programs in the world,” he says. “The arts program could be just as good. I’d like to see more of an arts community.” On that, there’s universal agreement.

|

|

phone: 773/702-2163 | fax: 773/702-8836 | uchicago-magazine@uchicago.edu