|

|

|

In the 1760s, says Divinity School associate professor Catherine Brekus, “literally hundreds of people” flocked to the house of a poor Newport, Rhode Island, schoolteacher named Sarah Osborn. What began as a small women’s prayer group, Brekus notes, grew into a religious revival with events more on the scale of modern-day rock concerts. Historians don’t know exactly how the meetings reached such levels; at the time ministers claimed that God had ordained them. But thanks to their popularity, Osborn, an early evangelical, took on pop-star status in Newport both as a powerful spiritual leader and as a committed Christian—in the face of extreme adversity and although she was a woman.

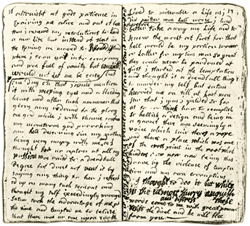

Brekus, at work on a book with the tentative title Sarah Osborn’s World: Popular Christianity in Early America, uses Osborn’s tale as a window into 18th-century American Christianity. Through Osborn, she explores both the typical female religious experience and women in religious leadership positions. Neither wealthy nor well-educated, Osborn was both an everywoman and an extraordinary one, accomplishing much within the bounds of a hierarchical and patriarchal society. What interests Brekus, an American religious historian, about the 18th century in general—and about Osborn in particular—is that she and her contemporaries “stand on the other side of a divide that is difficult to cross.” Profound changes in American culture, she argues, make it difficult for people today to understand someone like Osborn, who largely rejected the Enlightenment emphasis on reason and human potential, and believed, as a Calvinist, in predetermination. “She sees everything that happens to her as God’s will,” says Brekus, noting that modern-day readers are most troubled by the idea that Osborn believed that the tragedies she endured were divine punishment—and well deserved. Throughout her life Osborn suffered. She had a complicated relationship with her parents and contemplated suicide as a teenager. She married early to escape her family but her husband soon died, leaving her a young son. Her second husband had a breakdown (it’s unclear what sort) and she was left to care for him, her own child (who died at age 12), and several stepchildren. In her later years she developed a serious illness, possibly multiple sclerosis. When she died, her minister published some of her writings, acknowledging her unique place in Newport’s religious history. Osborn’s community saw her as a model, Brekus says, of “resignation and true Christian faith.” A “treasure trove” of Osborn’s writings—memoirs, devotional diaries, and correspondences, scattered among historical societies, research libraries, and universities in New England and Pennsylvania—form the basis for Brekus’s research. Unaware of those primary sources, modern historians have published next to nothing on Osborn. Brekus traveled around the Northeast, trying to piece together traces of the writings, and after much searching found some 1,500 pages. The pages reveal a great deal not about her daily life, which has only a marginal role in her journals, but about her spiritual awakening and her quest to inform others of the experience. Collectively, Brekus’s findings paint Osborn as a charismatic religious leader who spoke freely about being “born again” as a Christian and who regularly held religious gatherings at her home. But she was not a “preacher.” Osborn didn’t deliver sermons on biblical passages and was careful not to “move beyond her line” and usurp men’s function in the church, as she put it in a letter to Joseph Fish, a minister who questioned her religious activities. Osborn was, in fact, “very much an 18th-century woman,” Brekus notes—she read the Bible literally, including the passages that forbid women to preach. By recounting Osborn’s tale, Brekus, whose previous work includes the book Strangers and Pilgrims: Female Preaching in America, 1740–1845, shows that women did influence religious life, albeit informally, even before they were permitted to give sermons. Today they serve in the pulpits of many Protestant churches and in leadership positions in other faiths. Some denominations, however, continue to cite the same passages that kept Osborn from preaching. Her story, Brekus says, reveals the “possibilities and limitations” of women’s role in religion, past and present.—P.M.

|

|

phone: 773/702-2163 | fax: 773/702-8836 | uchicago-magazine@uchicago.edu

Investigations

Investigations