|

Religion

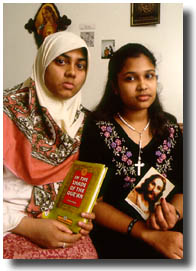

at Chicago is practiced in many ways, often by students who call

themselves more "spiritual" than "religious."

As my students and I clean up after the Thursday noon Eucharist

that has been a staple of the Episcopal campus ministry longer than

anyone can remember, we are careful—careful of the Salvadorian processional

cross our Catholic sisters and brothers use for their weekly mass;

careful of the hymnals used the day before in a weekly Divinity

School service; careful not to disturb the Muslim student who has

entered quietly, unrolled a prayer rug, and begun her midday devotion.

Passing Newberger Hillel Center on the way back to my office, the

aromas of its kosher lunch program scent the air. The signboards

of University Church and First Unitarian Church wear rainbow flag

decals signaling a welcome to lesbian, gay, and bisexual members

of the community. When campus ministers gather for their monthly

meeting, the circle includes as many women as men, more lay ministers

than ordained clergy, and representatives from a variety of practices,

including Asian American Students for Christ, Baha’i Students, U

of C Buddhist Association, and the independent evangelical Christian

congregation of University Community Church.

Catholics, Jews, Episcopalians, and the United Protestant Campus

Ministry maintain houses and full-time professional staffs offering

hospitality, worship, and programs. Lutherans, Baptists, and Unitarians

devote part-time clergy and lay leadership to campus ministry based

in local congregations. InterVarsity Christian Fellowship staff

coordinates student-led programs. This year’s religious preference

cards, optional forms returned by 25 percent of all registering

students, indicated that 29 percent identify themselves as Catholic;

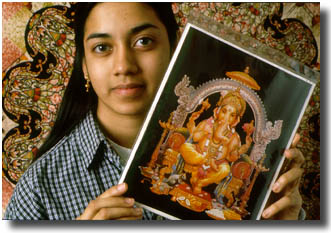

Jews and “mainline” Protestants number 12 percent; Lutherans, Episcopalians,

Muslims, and Buddhists each represent 2.5–3 percent; and Hindus

have grown to nearly 4 percent.

Catholics, Jews, Episcopalians, and the United Protestant Campus

Ministry maintain houses and full-time professional staffs offering

hospitality, worship, and programs. Lutherans, Baptists, and Unitarians

devote part-time clergy and lay leadership to campus ministry based

in local congregations. InterVarsity Christian Fellowship staff

coordinates student-led programs. This year’s religious preference

cards, optional forms returned by 25 percent of all registering

students, indicated that 29 percent identify themselves as Catholic;

Jews and “mainline” Protestants number 12 percent; Lutherans, Episcopalians,

Muslims, and Buddhists each represent 2.5–3 percent; and Hindus

have grown to nearly 4 percent.

|

These are visible expressions of campus religious diversity. Less

visible are a significant number who identify themselves as more

“spiritual” than “religious.” The present student generation is

probably no more or less spiritual than its recent predecessors,

though increasingly these seekers come to the quest with no previous

religious heritage to shed, except those vestigial remnants of civil

religion that survive in the culture at large.

Young adulthood is the point of conscious embarkation upon the

journey of our lifetimes: making meaning out of our existence. Colleges

and universities are acutely engaged in this launching, equipping

us with the intellectual and critical tools to examine everything.

Still, the campus is pretty hard ground; seed may fall here, and

may even take root for a while, but only the strong survive. And

this is as it should be. Religion spawned the universities and each

shares a common goal—the pursuit of truth, the search for ultimate

meaning.

|

The search takes many directions. That largely invisible cohort

of spiritual-but-not-religious students pursues a path worn smooth,

though they may believe themselves the first to walk it. Occasionally

one will ask for an hour in my office; a friend has suggested I

might be helpful. The student arrives with a defensively apologetic

explanation for his or her religionless status; my response attempts

to preserve the delicate uniqueness of this vantage while simultaneously

assuring that I can live with it. My role, as Anglican pastor Kenneth

Leech named it, is that of “soul friend.” It’s more than just listening,

offering counsel—though it may include both. It’s being with another

as that person encounters any of the many questions, pitfalls, or

pains that come of such exploration.

|

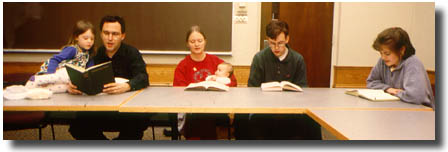

For others, this friendship is forged in long conversations over

beer at Jimmy’s or coffee in the Medici. Or in small groups who’ve

gathered to learn how to be women or men; lesbian or gay; African-,

Hispanic-, or Latino-American; or just how to be healthy, whole.

Whether students talk about their spirituality or not, it’s a significant

part of their lives. Introduced to ourselves as if for the first

time, we are often amazed, delighted, and frightened to discover

how complex we are. Set within so much diversity, we are challenged

to define ourselves. Given the variety we represent and the challenges

we present to one another, the true miracle is the high degree of

respect we experience here. With odd and statistically insignificant

exceptions, we are broadly tolerant, even appreciative of one another;

curiosity prevails over conversion.

Demographics on and off campus suggest that organized religious

life is changing drastically and traditional institutions stand

to be most radically affected. But the universal quest for meaning

is inherently spiritual. And if life at Chicago is indicative of

any broader trend, the future is rich with possibility. Those young

adults embarking on the search will likely find that, like learning

itself, this is a lifelong journey, and they’ll have lots of company

along the way, plenty of soul friends.

|