|

"Golf,"

commented Mark Twain, "is a good walk spoiled." Though

many share Twain's love-hate relationship with the game, golf's

appeal has flourished in the past century. So has the body of literature

about it.

By Kimberly Sweet

English

writer—and golfer—A. A. Milne had this to say: “Golf is popular

simply because it is the best game in the world at which to be bad.”

He may very well have something there. But a close reading of the

texts on golf—and there are many—suggests that the game’s surge

in popularity during the late 19th century had more to do with sweeping

social change: increases in leisure time, a new middle-class interest

in the outdoors and physical fitness, im-proved railroad and highway

access to courses, and new technology that made golf equipment cheaper.

All told, writes University Archivist Daniel Meyer, AM’75, PhD’94,

“For men and women, college students and children alike, golf was

an irresistible new expression of the contemporary age.”

Meyer’s text accompanies

the exhibition Reading the Greens: Books on Golf from the Arthur

W. Schultz Collection, on display in the University Library’s

Department of Special Collections through August 7. Currently numbering

more than 1,600 items, the collection is a gift from Arthur W. Schultz,

AB’67, a life trustee of the University and author of In Praise

of America’s Collectors: Their Secrets Reveal How to Be a Successful

Collector (Santa Barbara Museum of Art, 1998).

The rule books, instructional

manuals, catalogs, novels, club yearbooks, magazines, and coffee-table

books in the collection document the rapid growth of the game of

golf in the last 100 years, especially in the United States and

Chicago. “These are vibrant and fascinating research materials,”

says Alice Schreyer, curator of Special Collections. “The collection

will be very useful to scholars who are looking for material that

reflects social and cultural life.” For example, she says, women

golfers played an important role in the game’s development, and

the books reflect their changing status. Books on country clubs

and landscaping contribute to architectural history, while instructional

texts depict changes in how information is conveyed.

|

The exhibition culled

from Schultz’s collection explores golf’s origins, rules, techniques,

and tools, while also taking a look at caddies, duffers, and pros.

Women in golf receive featured treatment, as do golf humorists and

authors from Bob Hope (Bob Hope’s Confessions of a Hooker: My

Lifelong Love Affair with Golf) to James Bond–creator Ian Fleming

(Goldfinger).

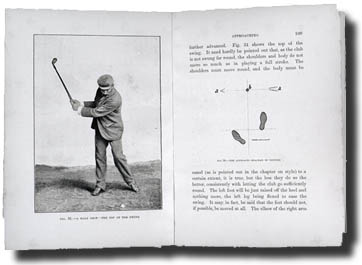

Instructional manuals

comprise perhaps the most popular genre of golf publications, according

to Meyer, who is also the associate curator of Special Collections.

William Park, Jr., two-time winner of the British Open and son of

the first Open champion, was the first professional player to write

such a book, The Game of Golf (1896). Other authors preferred

to address the sport’s mental aspects, with Alex J. Morrison offering

suggestions for mental imaging in Better Golf without Practice

(1940) and David C. Morley tackling the odd duo of Freud and golf

in Golf and the Mind (1978).

|

Though historians have

yet to pinpoint the origins of the game, and the Dutch seem to have

played a version called colf or colven as early as 1297, Scotland

is considered golf’s real homeland. The Scots were playing the sport

by the 15th century; by 1890, 387 British golf clubs had formed,

playing on 140 courses. From that era comes the oldest book on display,

the 1887 Golfing: A Handbook to the Royal and Ancient Game with

List of Clubs, Rules, & c. Also Golfing Sketches and Poems,

published in Edinburgh by W. & R. Chambers.

The first permanent

golf club in the United States—appropriately enough, with a Scottish

name—the St. Andrew’s Golf Club was established in 1888 in Yonkers,

New York. By 1900, the U.S. had 982 golf courses, and four decades

later that number had grown to more than 4,500.

Chicago more than kept

up with the pace. Scottish American Charles Blair Macdonald brought

golf to the Windy City in 1875. He founded the Chicago Golf Club

in 1893 and two years later, the club had built the nation’s first

18-hole golf course in suburban Wheaton. By the 1920s, an average

of one new course opened each month in the Chicago area. The exhibition

includes regional memorabilia such as books celebrating the centennials

of the Chicago Golf Club, the Skokie Country Club, and the Onwentsia

Club; yearbooks from several clubs; and issues of Chicagoland Golf

magazine.

An accompanying exhibit,

Maroons on the Greens: Golf at the University of Chicago,

includes golf pictures and stories from The Daily Maroon,

Cap and Gown, and the Special Collections archival files—not

to mention a ball used by the late GSB professor emeritus and Nobel

laureate George J. Stigler, PhD’38, to shoot one of his five holes-in-one.

Golf came to campus

in 1900 and received strong support from athletic director Amos

Alonzo Stagg, an avid golfer himself, until his retirement in 1933.

Student interest in the sport waxed and waned for another four decades

until the team ceased to exist in the mid-1970s. Just this spring,

though, a brand-new club of student golfers has taken to the links

at the Jackson Park course, the first course west of the Appalachians

to be open to the public and the place where the first University

Golf Club debuted.

|