|

Today Marty

sits on a dozen boards and has been given five dozen honorary degrees

as well as the National Humanities Medal and the Medal of the American

Academy of Arts and Sciences. He is the George B. Caldwell senior

scholar-in-residence at the Park Ridge Center for the Study of Health,

Faith, and Ethics, and he directs the Public Religion Project at

the U of C, where in March he gained emeritus status as the Fairfax

M. Cone distinguished service professor.

Despite his

stature, despite the remarkable visibility, when you ask the man

with the name how he'd like to be remembered, he says, "That I was

a good teacher. That's been my great joy, where I've always gotten

the most pleasure."

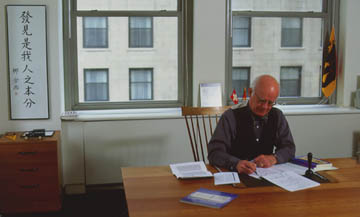

Entering Marty's

fifth-floor office at the Public Religion Project, across from the

Drake Hotel where Walton Street crosses Michigan Avenue, you spy

him before he sees you. He is seated at a table-framed within two

doorways, down a short hallway-reading, eating a bagel. In a sort

of telescopic fashion there he is: the man with the name. It is

a spacious corner office-glass all around, offering a lookout's

view of the rustling city streets, the honking cabs, and hurried

people. There are books and neatly arranged papers and framed, retro

posters of the old South Shore Line and a photo of Marty's father,

a Lutheran schoolteacher and organist.

You are dutifully

punctual, even fearfully early, because of Marty's reputation regarding

time. As in "Marty time"-reflecting, perhaps, the precision, organization,

and frugality genetically administered by his Swiss ancestry. Again,

the tales are legend. Days calibrated to the minute. His ability

to thrive on four, maybe five, hours of sleep. His 7-, 8- and 10-minute

naps scheduled throughout the day to refresh him-meticulously timed,

sometimes in full recline on his office floor, always a quick but

deep, reviving sleep. His knack for comfortably doing two, three

tasks at once.

This last habit

is especially unnerving to graduate students who diligently prepare

presentations then sweat through them-laboring insecurely-while

overseer Marty, last row of the classroom, appears distracted, preoccupied,

busily attending other tasks. He is reading, writing, checking his

mail, making notations in his checkbook, until the discourse is

complete. At which time he surgically dissects and masterfully elucidates

(in stunning detail) the presentation's strengths, weaknesses, finer

points, miscalculations.

You don't

want to be late.

But what you

find is that Marty greets you hospitably, warmly. When asked about

his achievements, he does not offer you a list of publications or

his curriculum vitae, his profile in Who's Who in the World, or

even the testimonials of those who nominated him (the list of nominators

itself a who's who) for the University of Chicago Alumni Medal,

which he proudly received at Reunion this year. Instead, he produces

a very, very long list of graduates on whose dissertations he is

listed as first adviser.

"I take more

pleasure," the professor explains, "in the fact that there are more

than 100 people I was thesis adviser to, more pleasure in a new

book by Scott Appleby or someone of his vintage, than one of my

own." R. Scott Appleby, AM'79, PhD'85, now director of the Cushwa

Center for the Study of American Catholicism at the University of

Notre Dame, was a research assistant under Marty and later worked

down the hall from him for more than five years while the two coedited

a landmark, six-volume study of religious fundamentalism around

the world.

"The grueling

schedule, the Marty pace, and the Marty quality," says Appleby,

"is not human." Yet what the protégé emphasizes is this: the Marty

parties, the ones for students at his 100-year-old home in the Chicago

suburb of Riverside, those Christmas and springtime festivities

with charades and door prizes; the hundreds, probably thousands

of letters of recommendations; the hundreds of scholars Marty has

guided as "unofficial mentor"; the countless number of people personally

helped. What Appleby emphasizes is that Marty "gives and gives and

gives to his students, far outspending them in generosity," that

he "is always thinking of other people, that everything is done

graciously, with a smile on his face, that service is very central

to what he does."

"Marty is not

God," Appleby told the 1996 gathering of the Society for the Scientific

Study of Religion, which gave the religious historian its career

achievement award that year. "But he is a condition of the possibility

for one. The workings of grace in him are powerfully transparent."

Indeed. This

past February more than 500 people helped Marty celebrate his 70th

birthday at a party co-hosted by his wife Harriet, Norman Lear,

and journalist Bill Moyers-who set aside some good-natured teasing

to say, "Martin Marty's God is a big-hearted God, and Martin Marty's

America does not shrink from, nor fear, the New World tribalism

that he himself saw coming 25 years ago. Perhaps his greatest contribution

is to remind us, over and over again, of the importance of telling

our stories of belief and practice, of hope and defeat, of loss

and the promise of redemption."

Given Marty's

accomplishments, given the intensity and fervor and dedication brought

to his life's work, to his teaching and writing, to his students

and colleagues and comrades in thought, the tireless productivity,

the drive and the will and the many applications of his knowledge

and gifts and wisdom, you expect to find a man less congenial, less

at peace, less serenely comfortable sitting back for an afternoon's

conversation. You also suspect that something has been neglected

or sacrificed in the pursuit of those many demands. Or that the

man's life has been charmed, tragedy free. Not so. On the contrary.

Marty married

Elsa Schumacher in 1952, the same year he was graduated from the

seminary and ordained. Despite the many demands imposed on the ambitious

scholar-teacher and despite the many callings from distant venues,

the young husband and father guarded and cherished his family time.

Saturdays especially were sacred days in the Marty household-an

extended family of six children, including two who joined the Martys

as foster children. This was in the mid-'60s when Marty, ministering

to migratory workers, grew close to and took in a 3-year-old boy

and 12-year-old girl. But there were others who came and stayed

and eventually moved on-two boys from Uganda, for example, and seven

or so adolescents who moved in, off-and-on, for various lengths

of time. "In the summertime," Marty recalls, "there'd be these sort

of inner-city strays living with us, kind of a UN under our roof."

Not only were

Saturdays devotedly reserved for family time, but the annual camping

trips became noteworthy expeditions, taking the Marty clan to 47

states, Canada, Mexico, and 13 European nations. Then there was

the 11-year period when the family retreated each summer to an island

harbor in Lake Michigan. But in the midst of these happily tumbling

years, Elsa was diagnosed with brain cancer, struggled for 10 months,

and died in September 1981.

At the urging

of a publisher Marty wrote A Cry of Absence: Reflections for

the Winter of the Heart, a personal meditation on those heartache

months of nursing Elsa. Now a classic in spirituality, the reflective

memoir and the response it generated has moved the scholar to write

other books dealing more personally with the Christian journey through

the contemporary landscape (including three collaborations with

his son Micah, a photographer).

In the midst

of this healing, Marty reconnected with a longtime friend, the widow

of his college roommate. He and Harriet, a mother of one, and a

musician and teacher who has better acquainted Marty with music,

the arts, and entertainment, were married in 1982-concrete evidence,

Marty has said, of the dramatic workings of providence in his life.

Harriet, it

seems, is the source of something you have heard about Marty, something

curious; because it is clear Marty is onto something-something that

makes him who he is, unique and special in the universe of scholars,

thinkers, theologians, writers. Appleby says it is because Marty

feels forgiven. Forgiven. You ask Marty if that is true, and what

he has been forgiven for. You ask about guilt and forgiveness.

He smiles and

tells a story about how one night Harriet had been troubled by some

things and how Marty suggested she not "take on the burden of all

this," to which she replied, "It would be helpful if you had a little

sense of guilt." Marty smiles again at the memory, then offers an

illuminating discourse on guilt and forgiveness, issues central

to Christian faith and redemption. He talks about the importance

of forgiving others-"a conscious willed act that comes in the form

of a gift, that becomes a way of life," he says, adding, "If you

see a person who does that habitually, you see a free person. If

I forgive you, it liberates me."

It is odd

that the subject has come up today, Marty says, because the Los

Angeles Times has just asked him to write a piece on forgiveness

and Bill Clinton, and he has recently contributed an essay to a

book dealing with forgiveness and the Holocaust. So he cites Paul

Tillich and he talks about Martin Luther's "core gospel of forgiveness"

and his attempts "to find a gracious God."

Then Marty

explains, "I make a great deal out of the words 'ordinary,' 'quotidian,'

'daily.' I believe very much in the sense of each day. There is

a Lutheran precept that we are born again every day, that we have

a new slate; and if you have made every effort at reparation and

reconciliation, and maybe talk to God a little, and if you then

wake up feeling guilty, it is your own fault. There is really no

reason to worry because each day takes care of itself."

You have heard

of people living in each moment and you have been told Marty is

one of these, that he has the ability to focus clearly and cleanly

on each task at hand, each student's problem, each puzzle begging

analysis, each demand on his time. Then he proceeds to the next.

He likes, he says, the word (if there is indeed such a word) "intrinsicality."

What he means, he explains, "is the integrity of each day, the intrinsic

worth of each act in each day, the intrinsic worth of the act you

are doing."

That, he says,

is the unifying principle at the center of his life. And as you

pursue that center, he tells you:

- that his

"model" has been Pope John XXIII, whom Hugo Rahner described as

"God's grave and merry person," an appellation Marty says he'd

gladly take as his own;

- that in

his role as a "public scholar" and "civic pedagogue" he has tried

to be "a fanatically faithful scholar";

- that his

"life quest" has been understanding and explaining the public

and religious pluralism and "what each takes from the other";

- that in

a life devoted to intellectual pursuits it is better "to be moored

rather than unmoored, to know where the port is"-his own "port"

being his "sense of roots," his "Nebraska Lutheran childhood"

to which he returns after venturing into "the cosmopolitan world

of academia, secularity, pluralism, and sophistication";

- and that

he is "not afraid of the home stretch."

This last derives

from a discussion of his "retirement" and whether or not he will

really be slowing down. "The ideal," Marty says, "would be to do

so; if virtuous, I would slow down." There are friends, he points

out, he'd like to spend "two hours with instead of 10 minutes,"

and he'd like "more balance between leisure and activity," recognizing

that "productivity and recreation are both virtues," and that there's

"a whole library of books on the shelf at home and I'd like to sit

on the porch and read through it."

But then there

was his spring project-a Divinity School conference on Narratives

in American Religion ("I love narrative. My theology is narrative,

is storied.") More books that "talk to the soul" to write. And more.

Yet more. Marty borrows a metaphor from an old friend who died at

age 102. "Life is a book of chapters," he says. "And I see my life

as a library book, one checked out long ago. The spine is now cracked,

the pages frayed. The book is well-read, perhaps long overdue, and

soon the library will call me in.

"But," he goes

on, "there's a new chapter, a new plot developing, new dramas, a

new set of assignments. I don't think anything is anticlimactic.

Each chapter surprises me. I look forward to the surprises in each

chapter."

The conversation

turns a bit, with Marty explaining how nervous he gets before preaching,

with him predicting trends in religion in the decades ahead, with

him talking about how he probably always knew he would teach and

write, about time management and his childhood and the day he and

a boyhood friend dropped in on Carl Sandburg. They were scolded

by Sandburg's wife and told the writer was busy upstairs, that they

should get along now. But soon the author himself came down and

scolded the boys and told them they were interrupting and intruding-before

inviting them up to his study for a gracious afternoon's talk.

This last is

an example, Marty says, of disponibilité, being flexible with one's

time, making oneself available to others. One of Marty's great gifts,

says Appleby, is captured in Eugen Rosenstock-Huessy's Respondeo

etsi Mutabor: "I respond even though I have to be changed."

In many ways,

you figure, Marty's life has been one of adapting, adjusting, responding,

being changed by the many ways he serves others, yet changing others

by the way he responds to them, to their questions, needs, requests,

petitions. Answering calls, God's calling.

Thinking of

the final call, you have to ask him, "Are you afraid of dying?"

To which Marty

responds smiling, deferring to Woody Allen: "I'm not afraid of dying.

I just don't want to be there when it happens." You both laugh;

Marty continues, "I could live with annihilation, extinction. We

will die, accidents happen, people will forget we ever lived. But

I am a terrible chicken about pain. And I do not, of course, look

forward to the painful decline of my powers. I saw my wife go through

brain cancer, and it's not a pretty sight."

Marty then

talks about the immortal soul, the difference between Greek and

Christian conceptions, the incomprehensibility of eternal life,

and how every morning he awakens at 4:57 a.m., three minutes before

the alarm is set to go off, and abides by "the Lutheran custom of

making the sign of the cross and saying a little prayer-a daily

reminder that you are mortal, that the body is mortal."

Of course,

it is clear to you-from the many people touched, the many words

written, the Divinity School's new Martin Marty Center to study

religion's role in public life and culture-that Marty's life is

richly layered, that his house has many rooms. And you know he has

found answers to questions still nagging you, that there is so much

more to learn from him. But you sense it is time for you to go,

time for him to get on with his life, to give his full attention

to the next task at hand. And as you walk away, looking back at

the professor returning to his office, you see and are glad that

the man with the name is inspiritingly human.

|