|

|

And

when? And why? And what's to be learned? Divinity School

professors Bernard McGinn and John Collins take an encyclopedic

approach to the end of the world.

|

|

|

|

|

The Encyclopedia

of Apocalypticism—1,500 pages of religious scholarship that

analyze how, when, and why humans since pagan antiquity have felt

compelled to imagine the world’s end—was born in a decidedly non-apocalyptic

moment: over Irish whiskey at Kitty O’Sheas, a Michigan Avenue pub.

There, one afternoon during the November 1994 American Academy of

Religion conference, Divinity School professor Bernard McGinn sat

down with an editor from the appropriately named Continuum Publishing

Company. Their conversation turned to the hype over the year 2000

and the significant amount of apocalyptic scholarship amassed during

the past 30 years. The time was right, they agreed, if not for the

end of the world, then at least for a standard reference chronicling

its coming.

Known among

his colleagues as “Mr. Apocalypse” for his more than 20-year immersion

in the subject, McGinn enlisted as coeditors Divinity School professor

John J. Collins, an expert on the origins of apocalyptic beliefs,

and Indiana University’s Stephen J. Stein, a former president of

the American Society of Church History. Taking a chronological rather

than alphabetical approach to the project, they chose to focus on

Western Judeo-Christian traditions, with some discussion of Islam.

Published this

past summer, the Encyclopedia charts the evolution of apocalyptic

thought in three volumes of 43 original essays by 42 international

scholars. Their sober research does not make apocalyptic predictions,

seek to validate or disprove certain theories, or, as the Library

Journal noted in its favorable review, offer fodder “for fans

of UFOs, crop circles, or the re-emergence of Atlantis or Mu.” Rather,

the essayists strive to illuminate how societies have struggled

with apocalyptic notions and reflected them in art, literature,

political rhetoric, and popular culture.

“Apocalypticism

isn’t going to go away,” says Stein. “What has kept these traditions

so powerful is our inherent desire to know what the future will

bring. These are deep, rich, powerful traditions that have continued

for hundreds of years and are as powerful as they ever have been

as the end of the millennium draws near.”

The

turn of a new millennium serves as a natural rallying point for

the apocalyptic faithful. Most current apocalyptic prophecies predict

the end’s arrival sometime between now and 2005, whether it’s marked

by Christ’s second coming, global tyranny, or natural disaster.

Though the word “millennium” can mean simply a span of 1,000 years,

for many people it invokes apocalyptic concerns, referring to the

1,000-year reign of Christ prophesied in the New Testament’s Book

of Revelation or to general cultural notions of a lengthy period

of perfection on earth. The

turn of a new millennium serves as a natural rallying point for

the apocalyptic faithful. Most current apocalyptic prophecies predict

the end’s arrival sometime between now and 2005, whether it’s marked

by Christ’s second coming, global tyranny, or natural disaster.

Though the word “millennium” can mean simply a span of 1,000 years,

for many people it invokes apocalyptic concerns, referring to the

1,000-year reign of Christ prophesied in the New Testament’s Book

of Revelation or to general cultural notions of a lengthy period

of perfection on earth.

“The year

2000 calls up issues of the meaning of history,” explains McGinn,

noting that the next 1,000-year period does not actually begin until

January 1, 2001. “The passage of the millennium has many people

thinking about whether the next millennium will bring a great crisis

in its early stage or a time of great human achievement.”

No wild-eyed

prophet himself, McGinn calls the millennial fever “overblown but

harmless,” and matter-of-factly says that “it’s a big mistake” to

read apocalyptic religious texts literally. Collins predicts that

“the world may well come to an end in the next 1,000 years, but

it will be the fault of humanity, not a divine plan.” And Stein

emphasizes his neutrality as a historian: “I’m not out to persuade

that some predictions are right and to debunk others.”

At the same

time, all three take their subject seriously. “These ideas are an

important part of history and still have power today,” says McGinn.

“It’s important to understand them and how to avoid their misuse.”

While every society weaves its own historical myths, he explains,

the three most prominent monotheistic religions—Judaism, Christianity,

and Islam—distinctly center on apocalyptic notions of a history

where God reveals himself at its beginning and its end. Without

an apocalyptic mentality, says Collins, “you wouldn’t have Christianity.”

Apocalypticism

thrived long before humanity faced the Y2K problem. Taken from the

ancient Greek apokalypsis—literally “an uncovering”—the word “apocalypse”

is defined by one standard English dictionary as “the expectation

of an imminent cosmic cataclysm in which God destroys the ruling

powers of evil and raises the righteous to life in a messianic kingdom.”

A more secular definition, writes Stein, generally refers to a “belief

in an imminent end to the present order, either through catastrophic

destruction and conflagration or through establishment of an ideal

society.”

While they

may differ in outcome, all apocalyptic tales comment on the future.

“There’s a very special temporal aspect to apocalyptic literature,”

says Divinity School professor Bruce Lincoln, who contributed an

essay on apocalyptic temporality. “It’s the sense of an immediate

future pressing on the present. It also expresses profound dissent

with the way things are.” Take the Book of Revelation, one of the

great apocalyptic touchstones. As Divinity School professor Adela

Yarbro Collins explains in her essay, the prophet John used symbolic

imagery and mythic language in Revelation both to comment on his

time and to transcend it. Through the story of a conflict between

a divine power and an evil beast, she says, John criticizes the

Roman emperor for fostering a growing inequality among his people.

Though some readers may look for a literal historical blueprint

in John’s writings, she argues that the texts are more truly symbolic

statements, full of details used primarily to make his rhetorical

points, just “as any artist would create a narrative vision.”

The typical

apocalyptic story, like Revelation, is one of good overcoming evil

in a dramatic, often violent struggle, with history culminating

in a day of individual or public judgment. “In apocalyptic literature,

religion is writ large,” says John Collins. “The supernatural overtones

are up front. Its powerful language and imagery provided the octane

in the fuel of early Christianity.”

Judaism, he

explains, first wove together and expanded the apocalyptic themes

of ancient cultures. The Torah borrows the idea of good versus evil

from Near Eastern combat myths, a moralizing tone from Persian myths

that envision a lasting division between light and dark, and a sense

of revelation from the Greeks and Romans, who presented a life beyond

this world. Judaism then adds angels, other netherworld emissaries,

and the idea that history is on a set course culminating in a resurrection

of the dead and a final day of judgment. Later, the Christians created

the expectation of Christ’s second coming, while the prophet Muhammad

made the goal of achieving justice on earth in preparation for the

coming judgment a central tenet of Islam.

Such dramatic

stories have provided inspiration for art and literature throughout

the centuries. “The phenomenon of the apocalypse is not just a matter

of theology but also of major cultural import,” says McGinn. Medieval

artisans, living in a time of church dominance and widespread epidemics,

produced some of the greatest works to capture the heightened sense

of doom and salvation found in the apocalypse. “Medieval folk lived

in a more or less constant state of apocalyptic expectation,” writes

McGinn, “difficult to understand for most of us today.”

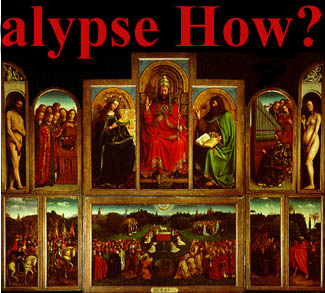

In her Encyclopedia

essay, U of C art history professor Linda Seidel examines one of

the period’s most ambitious works. In the Ghent Altarpiece—a

group of painted panels dating to the 15th century in St. Bavo’s

Cathedral in Ghent, Belgium—Jan Van Eyck depicted the prophet John’s

earthly paradise, New Jerusalem, in a lush scene that includes at

its center a bleeding lamb surrounded by angels and other holy figures.

Van Eyck’s work, Seidel concludes, spurred viewers of the day to

meditate on John’s words, lending them plausibility with recognizable

human, plant, and architectural images. The altarpiece, like much

apocalyptic art, she says, seeks to construct a “visual sense of

forecast or foreboding, the mood and mode of apocalyptic writing

wherein present and future are ineluctably intertwined.”

While the 20th

century’s apocalyptic appropriations may not always rely on fire

and brimstone, they are no less ominous. The Encyclopedia

cites Cat’s Cradle (1963) by Kurt Vonnegut, AM’71, as an

example of “annihilative apocalypse” for its imagined ice-nine substance

that destroys life by freezing all the earth’s water. Then there’s

Stanley Kubrick’s classic film Dr. Strangelove: Or How I Learned

to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb (1964) that, as Stephen D.

O’Leary of the University of Southern California writes, “demystified

the machineries of nuclear war and exposed the paradoxical absurdity

of the balance of terror.” Around the same time, O’Leary notes,

the rock band the Doors sang of violent passages to “the other side.”

In the 1990s, the Encyclopedia makes clear, apocalyptic rhetoric

has moved even further beyond the medieval priest’s pulpit: to the

Internet, where like-minded souls debate when the end will come;

to cable—witness televangelists like Jack Van Impe; and to the best-seller

lists, to which evangelical minister Pat Robertson’s The New

World Order—describing an Antichrist dictator aided by Jewish

bankers—ascended in 1991.

In its many

forms, apocalypticism has served many interests. The Encyclopedia

shows how it has provided hope for the oppressed, as when, during

their sixth-century Babylonian exile, the Jews drew strength from

biblical prophecy that their enemies would one day be overthrown.

For centuries, Christian church leaders have wielded apocalyptic

fears as a stick to encourage certain political and lifestyle changes

within the church government, clergy, and flock. During an 11th-century

campaign to restore moral purity to the clergy and church governance,

writes McGinn, Pope Gregory VII often warned that the need for change

became more important as the end drew nearer. Apocalypticism has

also provided an alternative religious framework. Stein chronicles

how, at the turn of the 19th century, German weaver and self-proclaimed

prophet George Rapp, along with 300 religious dissenters, founded

the pious Harmony Society to prepare for Christ’s second coming.

And contemporary scientists, the editors note, have employed apocalyptic

rhetoric to warn of the potential catastrophic consequences of global

warming, the AIDS epidemic, and nuclear war.

In the Encyclopedia’s

final, forward-looking essay, Divinity School professor emeritus

Martin Marty, PhD’56, notes the paradox of trying to ascertain the

future of a subject grounded in the idea that “the world as we know

it and time as we experience and reckon with it ultimately have

no future.” Marty suggests that there will always be a need for

such rhetoric as long as people are drawn to it through a sense

of duty-bound scriptural literalism, a need for mythopoeic fantasies,

or a desire to escape the present.

An apocalyptic

mentality may actually end up seeing us through the next millennium.

While some apocalyptic notions have been used to justify suicide

bombing and other destructive ends, John Collins maintains, the

overall effect of the apocalyptic impulse has been positive, providing

both “a store of hopeful imagery and the sense that problems will

eventually be overcome.”

|