Nattering

nabobs of negativity have a strategy that works as well as positive thinking.

Too bad it doesn't work for everyone.

Nattering

nabobs of negativity have a strategy that works as well as positive thinking.

Too bad it doesn't work for everyone.

What if you

don't finish reading this article? What if you don't even start it? What if the

statistics don't add up? What if it fails miserably at conveying its point? What

if you dislike its protagonist-an unassuming psychologist in Wellesley, Massachusetts?

What if you think her research is dumb? What if you think it's not only dumb but

out-and-out wrong-and you're someone who would know because you have your own

doctorate in psychology? What if the Magazine's printer leaves out the

story's last page, or the entire issue gets shredded in the mail? What if the

damn thing is full of typos or modifiers misplaced in embarrassing places? What

if all this fretting irritates you so much that the last thing you want to do

is continue reading?

Now

for a plan of attack.

Now

for a plan of attack.

Although the Magazine

can't control whether you like Julie K. Norem, AB'82-much less whether the printer

or the post office gets its job done-we can control accuracy, cite convincing

evidence, and provide the "Letters" section for you to tell us where

we-or Norem-err. We can proofread, check facts, muster our creativity, give it

our all despite everything that could go wrong.

As

for whether this multiparagraph exercise irritates you-well, you're probably a

strategic optimist, so you wouldn't understand. For those who hear yourselves

in this assembly of worst-case scenarios and contingency plans, welcome to Norem's

favorite research population. You're a defensive pessimist.

It's

mid-June on the Wellesley College campus, and Norem, a specialist in personality

and social psychology, is reading aloud from her letters file. "This is a

typical one: 'Dear Dr. Norem, For seven years I've read almost every positive-thinking

book on the market, yet my attitude steadily grew worse. My self-condemnation

for being so negative led to depression, anxiety, and terribly low self-esteem.

"'Then I found your book yesterday,'"

Norem reads on. "'There's nothing wrong with me! There was nothing wrong

with mom and dad either! We are all defensive thinkers! I cannot tell you the

freedom and release I feel. I even brought out my Eeyore toy. I always hated Eeyore

because I thought he was so negative. Not so.'"

Since

Norem's book, The Positive Power of Negative Thinking, was published by

Basic Books last December, she's received a steady stream of grateful responses.

Many come from therapists and clinicians who treat fretful, anxious patients,

the kind of people whom others avoid because their negative harping can be both

depressing and counterproductive-or so it seems to more optimistic types. Norem's

correspondents recognize in her research a workable method for helping such people

manage their anxiety and tackle intimidating tasks.

The

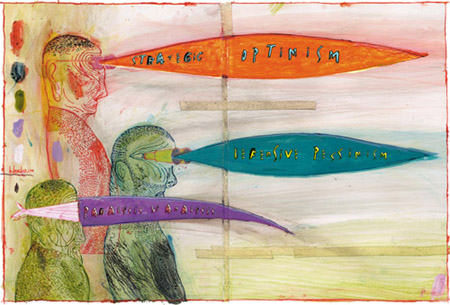

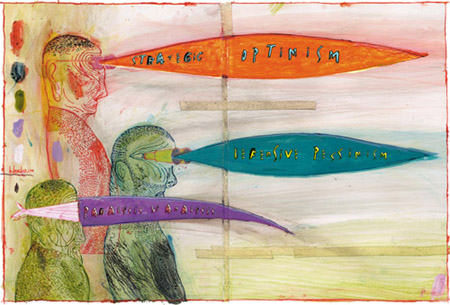

key to Norem's studies is where they begin. While her peers in academe divide

the world into positive and negative thinkers and preach the power of positive

thinking to the schlubs lumped in the negative camp, Norem draws different cross-sections,

leading her to make different recommendations. Rejecting "positive"

and "negative" as too general, she begins by looking at psychological

states, separating persons who are by nature anxious from those who aren't. Nonanxious

persons probably use what she calls strategic optimism.

Next

she seeks out those who are anxious about the future rather than those whose anxiety

stems from dwelling on the past-the latter are so-called dispositional pessimists

and are the subjects of most negative-thinking studies. Among the future-oriented

anxious group she distinguishes between those who can tolerate their anxiety enough

to accomplish their goals (defensive pessimists-Norem's specialty) and those who

are overwhelmed by it. Members of this last group tend to experience "premature

cognitive narrowing," or paralysis by analysis. They either avoid anxiety-inducing

situations entirely or subconsciously self-handicap by procrastinating or self-medicating

with drugs or alcohol when faced by daunting tasks.

Because

humans are complex creatures, it's possible to be more than one "type."

Which strategy you use, Norem explains, "depends. Everything depends"-on

the situation, on your environment, on what you consciously hope to achieve. In

any particular domain-work, social interaction, home life-about 25 to 30 percent

of Americans, Norem estimates, consistently use defensive pessimism, while 30

percent consistently use strategic optimism. That's roughly how subjects have

divided up in Norem's studies over 18 years. Her samples have ranged from 60 nursing

students to 498 Northeastern University undergraduates. (And the distinction about

nationality is important, Norem says, because Americans tend to insist on optimism.

In Asia defensive pessimism is more the norm. Since Norem's book was released

in Taiwan this past June - its title translated as I'm Pessimistic But I Achieve

- it's been selling like Starbucks.)

As for the

other 40 to 45 percent, we may be inconsistent in our strategy, flip-flopping

without noticing if one works better; we may have no strategy, avoiders and self-handicappers

who succumb to paralysis by analysis; or we still may be developing a strategy

because we lack experience in that domain or situation, as might be the case for

a parent preparing for her eldest child to go away for college.

Ultimately,

Norem says, it's all about goals. "A strategic optimist's unconscious goal

is not to become anxious. A defensive pessimist's unconscious goal is not to run

away." So defensive pessimists-who, despite being future focused, tend to

be very aware of their faults and past mistakes-conquer their urge to flee by

conjuring worst-case scenarios and a multitiered plan. But strategic optimists-who

are by nature positive about their past performance and confident in their continued

ability to do well-actively distract themselves from considering how they'll do

on the task ahead.

In her book Norem gives the

example of a strategic-optimist architect who reads travel brochures before big

presentations, while his defensive-pessimist partner is busy making extra photocopies

just in case. The self-handicapper, meanwhile, is still writing her presentation

in the taxi en route to the meeting, and the avoider sorts envelopes in the mail

room, too freaked out by the prospect of giving presentations to choose a career

that might require such a stressful unknown in the first place.

On

first impressions alone, one might conclude that Norem is a strategic optimist.

She's blond, has a confident stride, and on this particular day wears a brilliant

fuchsia blazer. Her book is written in a relaxed, chatty voice. She was recently

promoted to full professor. And while the prospect of developing an entirely new

psychometric methodology might lead a less confident researcher to stick with

laboratory experiments-Norem is among the first to study defensive pessimists,

so she's had to figure out the best questions to ask these new subjects-she has

created a solid portfolio of real-life and longitudinal studies.

Yet

her office has the tell-tale signs of a self-handicapper: piles of paper totter

on stacks of books, transparencies spill from three-ring binders. Of course, she's

one day away from her first sabbatical, so she may still be devising a strategy

for this situation.

When asked where she falls

on her research continuum, she first classifies herself as anxious (a fairly recent

self-discovery: "I've spent a lot of time and effort withholding anxious

feelings from myself"), then specifies her strategy by domain. At work, she's

a recovering self-handicapper striving to use defensive pessimism consistently.

"I can't think of a single time in my work life that I've been overprepared,"

she says. "It was a surprise to realize there was a more effective way of

dealing with things." At home she's a strategic optimist turned defensive

pessimist, the confident wife who never considered worst-case scenarios until

motherhood struck and her sense of control disintegrated in the peanut-butter-covered

faces of toddlers.

Telling a frazzled mother to

stop worrying and look on the bright side doesn't help her problem-solve, and

such advice, Norem has learned, is equally pointless for a defensive pessimist.

After

graduating from Chicago 20 years ago, Norem entered the University of Michigan's

graduate program in psychology, where she met professor Nancy Cantor, a defensive

pessimist who actually coined the term (and who is now chancellor of the University

of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign). Cantor taught Norem that, given the same situation,

some persons "see through the lens of anxiety and others don't."

After

graduating from Chicago 20 years ago, Norem entered the University of Michigan's

graduate program in psychology, where she met professor Nancy Cantor, a defensive

pessimist who actually coined the term (and who is now chancellor of the University

of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign). Cantor taught Norem that, given the same situation,

some persons "see through the lens of anxiety and others don't."

If

defensive pessimism was indeed a strategy for managing anxiety, Norem reasoned,

then interfering with it at critical points would demonstrate how the process

worked and whether it was as successful a strategy as positive thinking was typically

proclaimed to be. So she and Cantor ran a series of experiments intended to tinker

with defensive pessimists' thought processes. From a questionnaire similar to

that on page 51, they culled subjects who fell on the extreme ends of the defensive

pessimism/strategic optimism spectrum.

In one

study some defensive pessimists were asked to predict their performance on a standardized

test. Defensive pessimists, as part of their strategy and complicated self-concept,

tend to set low self-expectations before a task, building confidence by drawing

up contingency plans. Members of this group, true to form, expected to perform

poorly. Meanwhile, other defensive pessimists were simply assured that, given

their "records," they should expect to perform well on the test. These

subjects set significantly higher expectations for their performance than the

first group did. Norem guessed that, among these defensive pessimists, positive

expectations would cause complacency, resulting in a failure to use their tried-and-true

strategy for success. She was right: this group's performance fell well below

that of the first.

In another study strategic

optimists and defensive pessimists participated in a dart-throwing exercise. The

subjects were randomly assigned to prepare in one of three ways. The first group

engaged in what cognitive-behavioral therapists call "coping imagery,"

imagining something going wrong (such as hitting the researcher with a dart) and

taking steps to prevent it. The second group practiced what sports-psychologists

call "mastery," imagining a flawless performance. The third did a relaxation

exercise, distracting themselves by visualizing a peaceful scene such as a beach.

The study's defensive pessimists, Norem found, did best when they used coping

imagery. Their performance declined when they imagined performing perfectly, and

they did even worse when asked to behave like optimists and distract themselves.

In contrast, strategic optimists performed best after the relaxation exercise

and worst when they imagined things going wrong.

Norem

next wondered how forcing worrywarts to take their minds off their troubles by

keeping busy would affect their performance. She again provoked subjects' anxiety

with an aptitude test. Before the test some defensive pessimists were told to

outline possible outcomes; others were assigned random clerical work. The busywork,

Norem reasoned, would keep them from rehearsing worst-case scenarios. Her results

confirmed that suspicion: the second group's performance was considerably below

that of the first.

Worries, Norem concluded, are

exactly what defensive pessimists need on their minds. Trusting in their

abilities by setting high expectations or distracting themselves by "thinking

good thoughts" or staying busy can hinder their performance.

Because

life, unlike these experiments, doesn't exist in a laboratory, Norem tested her

findings in the real world. She asked 60 nursing students to outline their personal

goals, which ranged from "saving to buy a house" to "rescuing a

nephew from life on the streets." Subjects were equipped with beepers that

randomly reminded them five times a day to fill out a questionnaire about what

they were doing, whom they were with, how they felt, and whether their current

activity was relevant to their personal goals. Some subjects were also asked to

reflect on their progress toward those goals. At the study's end a semester later

the defensive pessimists-and only the defensive pessimists-who did the reflection

exercise reported less anxiety and more satisfaction. They also had made considerable

progress toward their goals.

Similar findings

came from Norem's longitudinal study of 90 members of the Wellesley Class of 1997,

whom she followed through various major life events beginning with the 1993 new-student

orientation. In each situation-entering college, choosing a major, graduating,

finding a job, engaging in intimate relationships, having a child, switching jobs

or careers-defensive pessimists' anxiety levels peaked before the event, as they

conjured frightening scenarios. Yet afterward they reported outcomes as successful

as those of strategic optimists.

Gaining

the tools to dig up our beloved Eeyore and finally understand him is no

small gift. And judging from the rubber necking in airports and on trains inspired

by a book whose proud purple and yellow cover touts the power of negative thinking,

Norem is onto something. Yet most researchers in personality and social psychology,

she notes with frustration, don't pay attention to her work. Those who do point

to her early longitudinal studies, which failed to prove that defensive pessimism

is an "adaptive" strategy-that is, one that leads to successful outcomes,

which she has now proven. Norem attributes this early failure to a lack of experience

with the methodology. Now that she's tenured and published-and has learned the

ropes of longitudinal studies-"I'm the token dissenter among the positive

psychologists at all the meetings," she jokes.

Gaining

the tools to dig up our beloved Eeyore and finally understand him is no

small gift. And judging from the rubber necking in airports and on trains inspired

by a book whose proud purple and yellow cover touts the power of negative thinking,

Norem is onto something. Yet most researchers in personality and social psychology,

she notes with frustration, don't pay attention to her work. Those who do point

to her early longitudinal studies, which failed to prove that defensive pessimism

is an "adaptive" strategy-that is, one that leads to successful outcomes,

which she has now proven. Norem attributes this early failure to a lack of experience

with the methodology. Now that she's tenured and published-and has learned the

ropes of longitudinal studies-"I'm the token dissenter among the positive

psychologists at all the meetings," she jokes.

And

there are many positive psychologists. Norem's research, in fact, calls into question

the methods of the positive-psychology movement that for the past two decades

has dominated academic research. The movement's emphasis on positive thinking

is intended, University of Pennsylvania psychologist Martin Seligman and its other

champions have said, to be an antidote to a field preoccupied with illness and

disorder.

Yet their work, argues Norem, inappropriately

lumps defensive pessimists in with other negative thinkers. Because defensive

pessimists report high anxiety levels and certainly sound pessimistic, they are

grouped with those who have negative dispositions and pessimistic attributional

styles, such as dwelling on the past and believing that nothing will ever go well-thoughts

defensive pessimists decidedly don't have. In fact, when anxiety is statistically

removed from pessimism studies, Norem has shown, defensive pessimists turn out

to be no more pessimistic than strategic optimists, who aren't dealing with anxiety

anyway.

Norem is not alone in studying negativity,

but her approach makes her distinct. At "The (Overlooked) Virtues of Negativity"

symposium, part of the American Psychological Association's 2000 meeting, she

was the only researcher focusing on strategy and process, goals and progress.

Being the odd person out hasn't affected Norem's

own disposition. Reflecting on her time at Chicago, she notes that she has very

few visual memories of people. "I think that's because I was listening to

rather than looking at them," she says. "We were always exploring an

idea for fun, over beer, over dinner. It was the only place I've ever been where

every discussion began with Aristotle."

Norem

credits Chicago for her persistence, and employing her defensive pessimism, she

focuses on the future. An interesting personality trait has shown up in the part

of her Wellesley Class of 1997 studies that tracks self-concept: the fear of being

an imposter. Until now, the "impostor phenomenon" has been accounted

for only anecdotally in psychology literature. Norem is intrigued. She's already

considering her next research population: a group of Illinois men about to become

fathers. She's devoting her sabbatical to reading everything she can find on impostors

and devising a methodology for her next longitudinal study. The big question for

the defensive pessimist in her now is, what if…?

![]() Contact

Contact

![]() About

the Magazine

About

the Magazine ![]() Alumni

Gateway

Alumni

Gateway ![]() Alumni

Directory

Alumni

Directory ![]() UChicago

UChicago![]() ©2002 The University

of Chicago® Magazine

©2002 The University

of Chicago® Magazine ![]() 5801 South Ellis Ave., Chicago, IL 60637

5801 South Ellis Ave., Chicago, IL 60637![]() fax: 773/702-0495

fax: 773/702-0495 ![]() uchicago-magazine@uchicago.edu

uchicago-magazine@uchicago.edu Nattering

nabobs of negativity have a strategy that works as well as positive thinking.

Too bad it doesn't work for everyone.

Nattering

nabobs of negativity have a strategy that works as well as positive thinking.

Too bad it doesn't work for everyone. Now

for a plan of attack.

Now

for a plan of attack. After

graduating from Chicago 20 years ago

After

graduating from Chicago 20 years ago Gaining

the tools to dig up our beloved Eeyore

Gaining

the tools to dig up our beloved Eeyore