In Turkey's Amuq

Valley researchers from the Oriental Institute focus on

big-picture patterns of the ancient world.

It was September in the Amuq Valley,

and the cotton was bursting its husks. On both sides of

the road stretched a sea of green flecked with white. Riding

north in a big Ford van, Jesse Casana, AM'00, stared out

the window, ignoring his colleagues' chatter. Whenever he

traveled in the Amuq, he seemed to lose himself in the landscape.

Sometimes he leaned his head out the window, like a dog

muzzling the wind, to get a closer look.

He was not admiring the scenery. He was

studying it, sizing it up, looking for clues to its past.

He was doing archaeology on the fly. Casana is a Ph.D. student

in Chicago's Department of Near Eastern Languages &

Civilizations and a researcher at the Oriental Institute

(OI). Usually his fieldwork was more systematic. He and

his colleagues tramped along a predetermined course, scrambling

up hillsides, cutting through olive groves, scanning the

ground for the residue of ancient civilizations. But even

from a passing car, a few scattered stones or broken roof

tiles glimpsed in a field might reveal the site of an ancient

village or hamlet. "There is so much out there,"

Casana explained, "a lot of our finds end up being

opportunistic."

|

|

Chicago

researcher Jesse Casana (right) and his Turkish colleague

Merih Erek stand above the Amuq.

|

There are two kinds of archaeology. One

is the work of pick and shovel, wheelbarrow and trowel.

It is expensive and time-consuming. Excavating an ancient

town or city requires dozens of workers to haul and sift.

It commits the young archaeologist to weeks of toil in a

hole ten meters by ten. It is what most people think of

as archaeology: Heinrich Schliemann exhuming the burnt layers

of Troy, Indiana Jones saving the Lost Ark. But some archaeologists

find it, well, limiting. Instead of pouring their energies

into one spot, they study the whole landscape, ranging widely,

by foot and motor; increasingly they gaze down from above

with the help of aerial and satellite photography. They

are searching for deeper landscapes, and the land is a palimpsest

that they read for the long-ago stories that humans have

written and rewritten into it. They look for broad settlement

patterns—not just the cities, but smaller communities

and farmsteads, as well as the roads, canals, river channels,

and fields that lay between. They investigate the forces

that shaped the landscape, including erosion, deforestation,

and the expansion and contraction of agriculture.

Even to an experienced eye, the endless

rows of cotton revealed little. But Casana had a trick in

his field bag. As Hanifi Topal, his cheerful Turkish driver,

headed north, Casana switched on his Global Positioning

System (GPS)—an instrument about twice the size of

a cell phone that could fix his position to within about

ten meters-and thrust it out the window. Back in Chicago

he had pored over black-and-white satellite photos from

the U.S. Geological Survey. The photos, taken by American

spy satellites in the 1960s and 1970s, reveal blemishes—archaeological

sites—on the valley's surface. From space even very

small sites show up as variations of light and shadow or

a slight discoloring of the soil. Site No. 290, on the photos

a dark circle about 150 meters across, lay invisible under

the cotton, but Casana was homing in on its coordinates.

"We're about a kilometer away," he announced.

The van crossed an irrigation canal, stopped, and everyone

piled out.

Casana's team that day included three

American graduate students, a Turkish professor of archaeology,

and a Turkish undergraduate. Casana had gathered them for

their diverse interests and expertise: one knew the Paleolithic,

another ancient Rome, still another the later Islamic period.

Following the GPS like a divining rod, Casana led them through

a ditch and across a bare field toward the cotton's edge.

He wore a floppy brimmed white hat, a long-sleeved white

shirt, and loose khaki trousers. The heavy Amuq clay clung

to his hiking boots. The GPS told the archaeologists they

were 160 meters away. When at last they waded into the cotton,

they found the ground littered with broken pottery. Casana

stooped and quickly gathered a few pieces, piling them in

a cupped hand. "This might be an early site,"

he exclaimed. Some sherds were dusky, others pale with daubs

of orange or black paint. "Look at this," he said,

holding out a gray, gently curved piece. "This is great.

It's Chalcolithic pottery of the oldest period of occupation-6500

to 4500 B.C." It was rare to find a site this old on

the Amuq, he said. Most lie buried beneath too many feet

of sediment or at the bottom of mounds built up by later

civilizations. He crouched in the cotton and picked through

the scraps, cast up from the dawn of human history on the

Amuq. He was deep into the landscape and loving every minute.

|

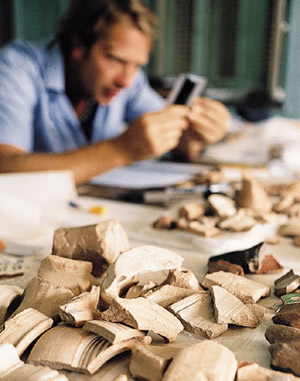

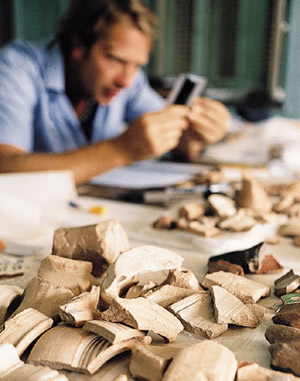

| Bryn Mawr grad

student Andrea DeGiorgi records sherds from Amuq sites. |

The Amuq

Valley lies in southern Turkey at the upper right-hand

corner of the Mediterranean Sea. It is a small patch of

the Fertile Crescent, the great arc through the Middle East

where agriculture and cities first appeared. To the east,

just over a range of hills, lies the upper Euphrates. The

Amuq is actually more plain than valley, a 30-mile-wide

expanse of cotton and wheat fields, irrigation ditches,

and scattered villages, bounded on three sides by hills

and mountains. The Orontes River loops through it, flowing

from its Syrian headwaters to the Mediterranean, but the

Orontes did not carve the valley. The Amuq is a rift valley,

formed by the same seismic shifts that opened up the Jordan

Valley and the Great Rift Valley of East Africa. Amuq, an

old name, comes from an Arabic word meaning deep.

(In Turkish the valley is usually called Amik Ovasi—ovasi

is Turkish for valley.)

Breaking the monotony of the plain are

many small, isolated hills. These are not natural features

but the sites of ancient towns and military fortresses,

built up slowly over hundreds and thousands of years. Some

are low enough to be cultivated by local farmers; others

jut 50 or 100 feet high. Not all are abandoned. In a few

places Turkish peasants live in concrete-block houses on

the buried ruins of Bronze Age towns. From almost anywhere

on the Amuq a dozen or more mounds are visible.

Blessed with rich soil, plenty of water,

and a mild climate, the Amuq has been prime real estate

since the beginning of agriculture. Humans have lived here

for perhaps 100,000 to 200,000 years, and it has been densely

inhabited for at least the past 8,000 years. In and around

the valley archaeologists have found the relics of Paleolithic

hunter-gatherers, Neolithic villages, Bronze Age kingdoms,

and outposts of the Roman Empire. At the plain's southeastern

corner, where the Orontes flows beneath a steep mountain

ridge, stood the ancient city of Antioch. Today it is called

Antakya and is the bustling capital of Turkey's Hatay province.

But until an earthquake destroyed the city in 526 A.D.,

Antioch was the greatest city of the Roman East. Its archaeological

museum has one of the world's finest collections of mosaics,

dug up from Roman palaces that still lie buried beneath

the modern city.

Among archaeologists the Amuq lacks the

allure of Mesopotamia, which lies hundreds of miles to the

southeast and is known as the heartland of cities. But it

has nonetheless attracted its share of attention. Between

1937 and 1949 the great British archaeologist Sir Leonard

Woolley excavated Tell Atchana, the capital of a small Bronze

Age kingdom. Woolley was drawn to the Amuq because it lay

at an ancient crossroads. To the north were the Hittites;

to the east, Babylon; to the south, Palestine and Egypt;

to the west, over the Beylan Pass, the Mediterranean and

the whole Greek world. "From the point of view of commerce,"

Woolley wrote in A Forgotten Kingdom (1953), the

Amuq was "the meeting-place of the Great Powers."

Chicago also sent teams to the Amuq.

Between 1932 and 1938 Robert Braidwood, PhD'43, the late

director emeritus of the Oriental Institute, explored the

valley, finding 178 archaeological sites and digging at

eight. But the gathering storm of World War II forced Braidwood

to abandon the Amuq. Woolley returned briefly after the

war but left for good in 1949. For decades no archaeologist

worked in the Amuq, in part because the political climate

had changed. In the 1930s the region was a Syrian province

administered by the French. After the war it became part

of Turkey, and Turkish officials steered archaeologists

farther east, where new dams on the upper Tigris and Euphrates

Rivers—part of an ambitious irrigation project—threatened

archaeological sites. "The Amuq Valley and Antioch

were put on the back burner, and nothing was done,"

said K. Aslihan Yener, a Turkish archaeologist and associate

professor at the Oriental Institute. "That entire region

fell asleep."

|

| Some sites,

like the village of Terzihöyük, or Tell Terzi,

are still inhabited. |

The region returned to the front burner

in 1995, when the OI started its Amuq Valley Regional Project.

Directed by Yener, the project revived, and enlarged, the

OI's interest in the Amuq. Working elsewhere in Turkey Yener

had developed an expertise in ancient mining and metallurgy.

The Amuq offered an opportunity to expand her studies to

fresh territory. She wanted to see, among other things,

what happened to the metals she had seen mined farther north

when they reached their markets. But the project was envisioned

as an ongoing effort that would encompass a range of archaeological

investigation. In addition to excavating some of the valley's

most important mounds—and revisiting Tell Atchana,

the Bronze-Age mound that Woolley excavated—archaeologists

would study the landscape to a degree that went far beyond

Braidwood's early survey. This part of the project fell

to Tony Wilkinson, another associate professor in the OI

and one of a rising generation of landscape archaeologists.

Born in England and trained in Canada

as a geomorphologist, Wilkinson has studied ancient landscapes

in Iraq, Syria, Turkey, and Yemen, where aerial photographs

helped him discover a Bronze Age civilization that no one

suspected could have existed so far south on the Arabian

Peninsula. In the Amuq Wilkinson is interested in long-term

changes in population and settlement. For him one important

story is the coalescing of settlement in the Bronze Age,

when centralized kingdoms emerged and people began living

exclusively in large fortified towns. He is also interested

in seeing how the Amuq changed as the valley came under

the sway of the great ancient empires, including the Assyrian

and the Roman. "We're looking at settlement changes,

changes in the ecological environment, changes in transport,

and how they all relate," he said.

At 53 Wilkinson is white-haired, energetic,

and given to expressions like "Right! Brilliant! Let's

go!" In fall 2002 he and two Chicago colleagues began

a project in Iran, which had barred Western archaeologists

since the Shah's fall in 1979, and in many ways he seems

to fit the Indiana Jones image of the intrepid archaeologist-adventurer.

In fact he is a pioneer of a kind of archaeology that has

become suddenly fashionable. "It's basically ancient

geography," he explained. "Traditionally archaeologists

have looked at specific archaeological sites and what's

in them. That's a narrow perspective. Our perspective gives

a much wider range of information on changing economies,

and especially how different areas interact with each other,

in terms of transport, agricultural production, and mineral

production."

Landscape archaeology is not new. Even

Schliemann's 19th-century study of Troy included the Trojan

plain. But landscape archaeology did not emerge as a separate

discipline until the late 1940s, when Harvard's George Willey

mapped ancient settlements, canals, and field systems in

Peru's Biru Valley. Then, beginning in the late 1950s, Robert

McCormick Adams, PhB'47, AM'52, PhD'56, later director of

the Oriental Institute, undertook a series of landscape

studies in Iraq. Adams, who went on to become secretary

of the Smithsonian Institution and is today an adjunct professor

in anthropology at the University of California-San Diego,

used aerial photographs to study remnants of the ancient

Mesopotamian landscape. He was able to determine what the

land looked like before and after cities began to form—how

scattered settlements gave way to urban centers. "That

was so popular it led other people all over the world to

begin similar kinds of studies," said Curtis Runnels,

a landscape archaeologist at Boston University and editor

of the Journal of Field Archaeology.

|

| Casana pulls

a Paleolithic stone tool from a layer of gravel. |

Casana, one of a half-dozen graduate

students who work with Wilkinson, is 27 years old and grew

up in Springfield, Virginia. "As a kid I was obsessed

with trying to find old stuff in parks or woods or wherever,"

he said. "I was always carting home boxes full of rocks

that I suspected might be stone tools, although I don't

think I ever found any. Sometimes I tried to make maps of

the places I went exploring. I always wanted to be an archaeologist.

Sometimes it was a paleontologist." During his first

season on the Amuq he took part in the excavation of an

older mound, Tell Kurdu. After that he began to work under

Wilkinson, gradually taking over much of the Amuq investigation.

The work has taken him over a lot of ground, sometimes by

car, more often on foot, in terrain that can be rugged and

steep but always full of surprises. "It's fast and

dirty and cheap," he told me over lunch one day in

Chicago. He was in the midst of planning his September fieldwork,

and he was brimming with enthusiasm. "We can go out

there and in a few weeks find stuff that challenges conventional

wisdom. We find a ton of things that people never knew existed."

I arrived in the Amuq in late August,

crossing over the Beylan Pass in a bus from Adana, a city

on the Mediterranean coast. The route was ancient but the

road was modern—a divided highway that wound down from

the pass to the flat green valley below. In the bus, which

was as sleek and modern as the highway, a young man wearing

a tie served Coke in plastic cups and squirted lemon-scented

lotion into the hands of the passengers. In Antakya I found

Casana and his colleagues living near the city center in

an aging four-story French colonial house, a few doors down

from the large buff-colored building that once housed the

French provincial administration and is today a pornographic

movie theater. Casana had rented the ground floor of the

house. It was cool and airy and cluttered with gear: cots

and sleeping bags, maps and satellite photos, reference

books, and plastic bags stuffed with broken pottery collected

the previous season.

|

| While the grad

student reaps clues to the past, an Arab family has

come to the Amuq to pick cotton. |

In the Amuq old civilizations reveal

themselves principally through their ceramics. Where people

have lived for long periods of time, the ground is usually

littered with broken pottery—fragments of water pitchers,

plates, bowls, cups, goblets, cooking pots, and large storage

vessels called pithoi. As fashion and technology

changed over time, so did the pottery, and by studying this

ancient refuse, archaeologists can determine with remarkable

accuracy when a site was inhabited. And while newer layers

of settlement cover older ones, the old does not usually

stay covered. After thousands of years, bits work their

way to the surface. Worms, burrowing animals, wind and rain,

tree roots, plows—these are some of the instruments

that turn the soil and bring up what is buried. Without

lifting a shovel or a trowel, an archaeologist can simply

examine this surface litter and know a site's full range

of occupation.

The day I reached town, Casana and his

crew were getting impatient. He had arrived in mid-August

with ambitious plans for two months of fieldwork. In the

Middle East, fieldwork generally takes place in the autumn,

after the summer heat has passed, and usually lasts only

a few weeks. Casana had hoped to spend much of the field

season exploring the hills around the Amuq, looking for

the kind of small, dispersed settlements he and others had

already found in abundance on the plain. But archaeology

is politically charged and fraught with obstacles. Much

archaeological effort, it turns out, is expended in a perpetual

quest for permits and endless wrangling with officials.

Casana's permits had hung up somewhere

in the Turkish Interior Ministry—he didn't know where

or why. So instead of spending their days covering new ground,

Casana's team stayed in Antakya and recorded the previous

year's potsherds. It was dull but necessary work. They emptied

plastic bags, measured the contents with calipers and diameter

charts, and made careful sketches on pale blue graph paper.

To a trained eye, the sherds were more than fragments; a

small slice of a rim or crook of a handle might blossom

in the imagination into a whole bowl or drinking cup. Laid

out on a table, the fragments spanned 8,000 years of human

history and many ages of the Amuq: Chalcolithic, Early Bronze,

Middle and Late Bronze, Iron Age, Hellenistic and Roman,

Late Roman and Early Byzantine, Middle Islamic.

|

|

Casana trods

a freshly plowed field above the Amuq.

|

One morning Casana and his colleagues

left on an excursion that was part reconnaissance, part

tourism. They stopped at site No. 290, filling in that blank

spot on the map of the Amuq. "I like to find a new

site every day," Casana said. "Otherwise I feel

I'm not really working." They also visited Tell Atchana,

where Woolley's old dig house still stood, an abandoned

two-story timber-frame building. Some of the ruins Woolley

unearthed had been left uncovered: mud brick walls built

in the Bronze Age and Woolley's "Stratification Pit,"

dug down more than 50 feet to the layers at the bottom of

Tell Atchana. This coming autumn Tell Atchana will be bustling

again as a team led by Yener and OI associate professor

David Schloen resume excavations. A single guard stood watch.

Then an old man hobbled up to see who the visitors were.

He wore sandals, a red-and-white head wrap, and baggy charcoal-gray

trousers with the crotch at the knees, a style favored by

older Turkish men. Ali Yalçin introduced himself

as one of Woolley's workers from the 1940s. "I was

just a zambil," he said—a boy who hauled

dirt in a basket. He leaned on his walking stick and grinned

a broad, toothless smile. "It was good work."

The permit

arrived at last, thanks to the intervention of the

U.S. embassy in Ankara. The next day Casana and the others

drove out of Antakya by 6:30, just as the city began to

stir. On one street corner men with shovels gathered in

the hope of work as day laborers. A man pushed a cart of

round, pretzel-like breads along the street. The archaeologists

drove east, following a two-lane road along the base of

the low, brown hills bordering the plain. They stopped at

the mouth of a small valley where a low hill, Casana explained,

was the mound of an Iron Age city. "I want to get some

early material, which might be hard to find and might not

be here at all."

The students set to work, prowling the

hill for bits of pottery. Casana led Merih Erek, a professor

at Mustafa Kemal University in Antakya, down to a gully

where a stream had cut through deep layers of alluvial gravel,

exposing the stones of an old Roman dam or mill foundation

and a later wall. Such discoveries were crucial; they would

allow Casana to date the alluvium and the erosion that had

produced it. The two archaeologists scrambled to the gully's

bottom, stood before a cut bank about 20 feet high, and

scanned the layers of gravel. Toward the bottom of the ban,

Casana noticed a piece of flint, hard and shiny against

the dull gray limestone gravel. He wiggled it free. It was

a "lithic," an old stone tool. Sometime about

100,000 years ago, in the Middle Paleolithic era, a scalloped

edge had been chipped into it by some ancient Amuqian. Casana

looked more closely at the layer. He spotted more flints

and pried them loose. The gravel was thick with lithics,

washed down from somewhere above. "It's likely there's

a Paleolithic site up the valley," he said. "It

might be hard to find, but it's probably there." He

turned to his Turkish colleague, who dreamed of finding

a Paleolithic cave. None had yet been found in the Amuq.

"What do you think?" Casana asked. Erek grinned.

"I am a very happy man."

An hour later they were grinding up a

narrow road past the squat, concrete-block houses of local

farmers and up into the side valley. The hills were parched

and brown, in sharp contrast to the irrigated fields of

the Amuq below. It would be more than a month before the

autumn rains arrived. Even the steepest slopes were a patchwork

of olive groves and small fields with wheat stubble, scraggly

cotton, melons, and tobacco. The previous year, Casana and

Wilkinson had begun exploring these hills, looking for archaeological

sites. In such rough, uneven terrain satellite photos were

of little use; they work best on the plain, where only slight

differences in uniformity stood out clearly. In hill county,

archaeologists were forced to use an old-fashioned method—walking.

Casana and the others spread out at 100-meter intervals

and set off in a ragged line up the valley, scanning the

ground as they trudged along.

|

|

Ali Yaçin worked as a dig boy for British archaeologist

Sir Leonard Woolley in the 1940s.

|

"It's a lot more systematic than

it looks," Casana said. "What we're trying to

do is just to sample this area of the landscape to see if

there are any sites on it. The problem is we have to cover

all parts of a valley, so we know where sites are, but also

so we know where sites aren't." They were looking for

any scrap of a human artifact—a broken roof tile, a

potsherd, maybe even a flint scraper. No matter how small,

an archaeological site would show up as a patch of broken

pottery, surrounded by a more diffuse "halo" of

potsherds. "When you're near a site," Casana said,

"you know it."

The ground was uneven, the slopes steep.

The sun blazed down, and a dry, constant wind blew from

the west. Communication became difficult. They were spread

out too far, and the wind was too loud, for shouting. Casana

tried hand signals, but mostly he used his cell phone. Everyone

carried a phone; it was an essential piece of field gear.

He dialed Alexandra Witsell, a Chicago grad student about

200 meters away. "If you see one sherd, look for more,"

he told her. "If you see more, we may be on to something."

The wind carried sounds up from below.

Somewhere a rooster crowed. A sheep bleated, a child shouted.

Suddenly Casana stopped and bent down. "Here's a little

bit," he said. He walked a few feet. "Here's another

little bit." He tossed aside two small orange chunks

of badly worn pottery and gazed up the slope. "I feel

there's something up there, and we're just skirting the

edge of it." He climbed through rows of spindly cotton

to the edge of an olive grove. A piece of a broken roof

tile lay in the dirt; he kicked it with the toe of his boot.

"These kinds of things are a lot more immobile,"

he said. He spotted a thick, slightly curved chunk of pale

orange ceramic, probably the broken rim of a storage jar.

The archaeological museum in Antakya had many of these giant

pithoi—fat, deep, and bigger than refrigerators.

Casana stood for a moment, puzzled.

"These are the kinds of places I

hate," he said. There were too few potsherds to make

a site, but too many to ignore. "Wait," he said

at last. "Look here." Thirty feet away, on a patch

of bare ground, lay a few small building stones, broken

roof tiles, and little stone cubes of Roman flooring, called

tesserae. "Yes, here it is," Casana said,

relieved. The scattered potsherds extended into the olive

grove, and he walked quickly around the perimeter of what

seemed the densest patch. AS 291, as he named it in his

notebook, was not large. "It's probably a little thing,

a farmstead, 50 meters or so, but it's real," he said.

"It's about the bottom end of what you find. It was

probably just a few houses." He pulled a plastic bag

from his shoulder sack and began to collect samples. "This

is very typical of the sites we've been recording the past

five years." He picked up a thin, delicately curved

piece of orange pottery. "It's early Roman, probably

the first or second century A.D.," he said, slipping

it into the bag. Özlem Dogan, the Turkish student,

hiked up to help. After ten minutes, they poured their bags

out and selected samples to keep. These were the ones that

seemed the most diagnostic—pieces that could be pinned

to a specific period. "Good," Casana said as he

fingered the sherds. "Very good." He held up a

heavy chunk of a pot rim. "What's this?" he asked.

"Pretty ugly." It went into the keep pile. "We

have to be pretty aggressive about culling this stuff in

the field," he said. "Otherwise we end up with

massive amounts of material." Then he sat down in the

shade and jotted some notes. He took coordinates from his

GPS. His phone rang. Asa Eger, another Chicago student on

the team, had found a second site in an olive grove a little

way up the valley. They had already found two new sites,

and it was barely lunchtime. "It's been a good morning,"

Casana said.

They ate a meal of feta cheese and bread

in the shade of some olive trees, then continued their tramp

up the valley, finding several more sites, collecting more

potsherds, taking careful notes. The next day they returned

and surveyed some of the higher slopes, struggling up a

steep, windswept hillside that yielded nothing but a view.

The Amuq plain stretched below, the cotton shining bright

green in the morning light. "Our objective is to understand

the whole landscape," Casana said, standing with his

back to the wind. "We have to sample the whole area,

the steep rocky hillsides, the streambeds. We have to demonstrate

where there aren't sites. A lot of my colleagues don't like

this part." The wind boomed across the hills, shaking

the wheat stubble. "How do they even get a plow up

here?"

|

|

A Cold War satellite map shows ancient mounds in the

Amuq.

|

After surveying the first valley, they

moved on to others. It was exhausting work. Tramping over

the hills left them sore and weary. But they were finding

new sites every day. Some were the size of hamlets and villages;

others were, in Casana's words, "crappy little farmsteads."

Slowly, however, they were filling in the landscape's story—a

story of dramatic change. Until late in the first millennium

B.C., most people in the Amuq lived in a few large towns

and villages. Then they spread out, moving into smaller

and more dispersed settlements, into villages, hamlets,

and crappy little farmsteads. Casana and others had found

dispersed settlements on the plain itself. Now, exploring

the small valleys in the fringe of hills, they discovered

that the expansion had been upwards as well. "Virtually

all the sites date to the first century A.D.," Casana

said. "By then, there's a huge population in these

villages." The settlements seem to have flourished

until the eighth or early ninth century. By the tenth or

11th, most were abandoned.

Another part of the story involved environmental

change. As people dispersed on the Amuq and moved into the

surrounding hills, there was an increase in erosion that

lasted for hundreds of years. But Casana couldn't yet say

why. Did farmers cause the erosion by cutting forests and

clearing new fields? Or did erosion increase when farmers

abandoned terraces on steep slopes? Many basic questions

eluded explanation. Why did settlement patterns change in

the first place? What compelled people who had lived for

millennia in large walled towns to spread out into villages,

hamlets, and farmsteads, and then to abandon them centuries

later?

"There are a lot of unknowns,"

Casana said one afternoon, pausing on a high slope. "We

have all these small sites. There are hundreds of years

of occupation. It's hard to know what's going on."

Later, over dinner in an Antakya restaurant, he explained,

"The more you look into these questions, the more you

realize you can't really answer them. Our knowledge and

our methods are just too crude."

It was a problem that had long troubled

him. "All archaeology is like that," he said another

time. "What we want to know are things about action

and belief in the past, and what we have are potsherds on

the ground. Even if you dig them up it's still just more

stuff, unless you have texts, and even then it is fraught

with problems. How to reconstruct action from object is

one of the old central problems of archaeology. I try in

my own work to ask questions that the data can answer, but

it's hard. I can address something like when did settlement

become dispersed into the hills, but I can't really do much

more than to speculate and argue about why."

I stayed

about a week on the Amuq. By the time I left the

cotton pickers had arrived in the valley. They were mostly

poor Kurds and Arabs from eastern Turkey. They pitched canvas

tents next to the fields and collected wheat chaff and old

cotton stalks to burn for cooking fires. Far off in the

fields whole families were already at work, specks of color

bobbing in the green. Preoccupied with reading the Amuq's

past, the archaeologists barely seemed to notice the present.

They would stay on for another fortnight. Wilkinson joined

them, and they worked harder than ever, going out in the

morning, returning for lunch and rest, then going out a

second time in the afternoon. There was, Casana said later,

"So much to do, so little time."

|

|

Going to a site

Casana and Erek (in cap) are, as always, accompanied

by a Turkish official.

|

And so much ground to cover. They returned

to site No. 290 and found, beneath the cotton, a rare agate

stamp used to imprint the clay seal of a jar or basket.

(The archaeological museum in Antakya later claimed it for

its collections.) They crossed the Amuq and explored the

slopes and valleys of the Amanus Mountains on the plain's

north side, discovering settlements no higher than 600 meters,

which happens to be the ecological limit of olive cultivation.

Perhaps, they speculated, the dispersal of settlement around

the Amuq had been caused by farmers seeking to expand olive

production. They discovered that a site near the Beylan

Pass was older than had been thought, confirming that the

pass had been part of an ancient trading route to the Mediterranean.

And they found a site in a hard-to-reach forested area that

may have been a summer resort for wealthy Romans fleeing

the hot summers of the plain.

Wilkinson left in the third week of September,

heading to Iran, and Casana and the others ended their fieldwork.

They had hoped to do more, but they no longer had permission

to keep working. In any case they were exhausted. "The

season was a great success," Casana said back on campus,

where he is spending the year writing up his dissertation.

"Everybody got along, and we got a lot done."

But his thoughts were already racing ahead to his return

and further explorations in the mountains on the plain's

north side. "We found fascinating things up there,

and there is a lot we don't know about them," he said.

How dense were the settlements in the high valleys? What

were people doing there, anyway? Were there mines, quarries,

and roads? He also wanted to look harder for a Paleolithic

site. He and his colleagues had found plenty of stone tools

on the Amuq; maybe they could also find a cave where the

makers had lived. Someday, too, he dreamed of doing a full

archaeological survey within the city of Antakya, looking

for ruins of ancient Antioch. The buried Roman city is thought

to be inaccessible, but just driving around he had already

found bits of it on Antakya's outskirts, where new construction

is exposing-and destroying-archaeological sites. The search

for ancient landscapes led in all sorts of directions, and

to many more seasons on the Amuq.

![]() Contact

Contact

![]() About

the Magazine

About

the Magazine ![]() Alumni

Gateway

Alumni

Gateway ![]() Alumni

Directory

Alumni

Directory ![]() UChicago

UChicago![]() ©2003 The University

of Chicago® Magazine

©2003 The University

of Chicago® Magazine ![]() 5801 South Ellis Ave., Chicago, IL 60637

5801 South Ellis Ave., Chicago, IL 60637![]() fax: 773/702-0495

fax: 773/702-0495 ![]() uchicago-magazine@uchicago.edu

uchicago-magazine@uchicago.edu