|

|

|||||||||

|

The call to the U of C radiology department came from Cooperstown the evening of June 4. They needed evidence, proof, X-rays. They needed them fast, and they needed them kept quiet. The urgency and secrecy had nothing to do with life or death, with patient confidentiality, with HIPAA run amuck. It had to do with history. The Baseball Hall of Fame had a hero with a hole in his honor.

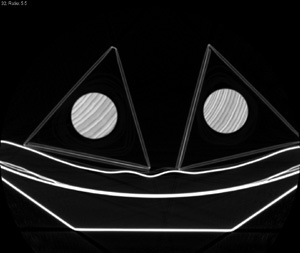

The whole sad tale began at Wrigley Field on June 3, when Chicago Cubs superstar Sammy Sosa hit a grounder to second base during the first inning of a game against the Tampa Bay Devil Rays. His bat shattered, and so did Sosa’s reputation: the broken bat had been hollowed out and filled with cork. Corked bats are illegal in Major League Baseball; bats should be solid wood. Scientists who take an interest in such things have found no real benefit from corked bats, but the superstition of their advantage in hitting balls farther and the rules against them persist. “Corked bats aren’t a mortal sin,” Robert Adair, Major League Baseball’s former official physicist, told a Nature writer, “just a venial one.” For almost any other player it would have been a minor infraction. But this was Sammy, the power hitter, all-around good guy, and shining glory of a team with an unsurpassed tradition of gloom. Before the game was over all 76 of his bats were confiscated from the locker room. They were X-rayed the next morning and found to be cork-free. That one shattered bat, however, cast a shadow of suspicion over a career that, at that point, included 505 home runs. Fortunately the Baseball Hall of Fame owned five of Sosa’s bats. Three were examined and found clean. But the two most important bats weren’t in Cooperstown. They were at Chicago’s Field Museum, part of a traveling exhibit called “Baseball as America.” Sosa had used one of those bats to hit his 500th home run and the other to hit home runs 64, 65, and 66 in his 1998 slugfest with St. Louis Cardinal Mark McGuire. “Think back to the race with McGuire,” says Richard Baron, the University’s radiology chair and the doctor brought in to diagnose the two crucial bats. “For the first time ever Roger Maris’s season record of 61 home runs was broken, and Sosa was neck-and-neck with McGuire. If he were ever going to use illegal aids, don’t you think he would do it then, when it mattered most?” So by 6:30 the morning after the call, Baron was at the Hospitals to meet a delegation from the Field Museum, the Hall of Fame, and Major League Baseball. They selected him for his proximity, radiological expertise, ability as chair to make things happen fast, and his lack of bias—he’s a Red Sox fan. “There was tension,” Baron says. “Oh, there was tension. They wanted to get it done. They wanted good news. Then they wanted to get the bats back before the exhibit opened.” The bats were carried into radiology in a cloth bag. Inside the bag each bat was protected by a cardboard box. A Field Museum curator donned latex gloves. She pulled the bats out one at a time, laying them diagonally on an X-ray machine. Milton Griffin, assistant director of imaging services—and a Cardinals fan—set the parameters, labeling each image as a lower extremity of one Richard Baron, and took the picture. “I’ve never imaged cork,” Baron says, “but I drink enough wine to know what cork would look like. We could tell right away that the bats were clean. Trust me,” he chuckles, “the baseball people were quite relieved. They were as relieved as families with a loved one on the table.” By then the museum and baseball staffers were ready to leave. They had the results they wanted, the bats in their boxes, and the boxes in the bag, and they hoped to get them back before any “Baseball as America” exhibit visitors noticed they were missing. But Baron wasn’t done. “It’s just my background to be thorough and detailed,” he explains. The X-rays may have been clear and quite convincing, but a radiograph is a composite. “It collapses everything into a two-dimensional image, so you can’t really see the internal structure.” He wanted to CT scan the bats. Instead of one image of the entire bat, a CT scan would produce cross-sectional slices right through the bat, like a stack of little pancakes, each four millimeters thick. “It would be apparent to anyone and absolutely persuasive that this was solid, homogenous wood.” The world’s first BatScan—taken without unpacking the bats—confirmed the initial diagnosis. That afternoon the League announced that the images showed “no evidence of cork or other materials banned by Major League Baseball.” The X-rays were published in newspapers and magazines. But the radiologists were more captivated by the CT slices. “You could see the grain, the gently curving lines of dark wood against a background of lighter wood,” Baron says. “It was beautiful.” Though he’s received more attention for his bat scans than for any life-saving image, “This is not how we normally spend our days,” he notes. Still, it was time well spent. “People teased us about doing something so silly, but in the end a lot of Americans think more about baseball than they do about health and medicine. They have faith in role models, and in our small way we helped restore some of that.” —John Easton

|

|

Contact

|