|

|

|||||||||

|

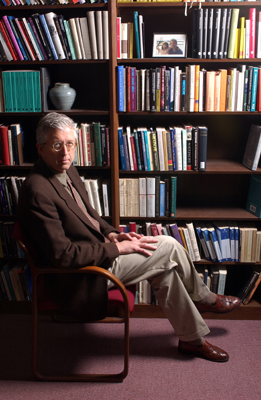

While postmodernists declare modernity dead, Robert Pippin says the movement—and its preeminent philosopher—are misunderstood. After working on a book called Hegel’s Practical Philosophy for 13 years, Robert Pippin says he needs just one more year—“to write a couple more chapters and link it all together.” For the Raymond W. and Martha Hilpert Gruner distinguished service professor in the philosophy department and chair of the Committee on Social Thought, 2003–04 should be the year. Pippin will be at the Wissenschaftskolleg zu Berlin—Berlin’s Institute for Advanced Study—trading ideas with 40 scholars from around the world.

Berlin suits Pippin, who, a month shy of 55, has taught at the Humboldt University, has given papers at other universities there, and sits on a German foundation’s advisory board. He began focusing on modern German philosophy as a second-year graduate student at Pennsylvania State University. His department had a week to nominate one person for “a big, two-year fellowship,” he says, “and all I had been working on at the time was Kant,” so he wrote his dissertation on Kant and Plato. Kant gave way to what he calls a typically German theme: “how to come to terms with a new form of life, modernity.” He continues, “It struck me that the more we learn about changes in human life after the 16th century”—when most scholars mark the onset of the modern world—“the clearer it becomes that [the change] was unprecedented and radical. It seemed important to try to figure out the role of philosophy in such an altered condition.” People began to value institutions such as private property, to question religion’s public role, and to adopt a Newtonian, scientific world view. And though many scholars believe such a shift is a subject for historians or sociologists, Pippin says, “It really goes to a deep normative question: what’s a reason or justification for action in one place at one historical time?” Two years before joining Chicago in 1992, Pippin—who this year earned a faculty award for excellence in graduate teaching—began his book on Hegel, considered the preeminent philosopher of modernity. He planned to write about the philosopher’s ethical and political theory but realized he’d first need to examine Hegel’s theoretical account of human agency. “I’m also trying to make Hegel responsive to contemporary ideas in philosophy,” he says—a topic he first broached in Modernism as a Philosophical Problem: On the Dissatisfactions of European High Culture (Blackwell Publishers, 1991; 2nd edition, 1999) and Idealism as Modernism: Hegelian Variations (Cambridge University Press, 1997). Hegel’s Practical Philosophy will extend and try to deepen such arguments. Hegel’s central question, according to Pippin, is: what is it to live a free life in the modern world? While Hegel, like Kant and Rousseau, believed that a necessary condition for living such a free life was the ability to recognize oneself in one’s thoughts and deeds, he didn’t believe it was a condition that one could satisfy as an individual. To Hegel, as Pippin puts it, “being able to lead a free, rational life is inseparable from participation in an ethical form of life, from offering justifications to others who accept or challenge them.” In other words, modern societies offer freedom but only within the context of communities—the modern family, the modern market, the liberal-democratic state. It’s a collective, jointly achieved rather than individual freedom. That communal focus has led to charges that Hegel undervalued individualism and crept into conformity. He was roundly criticized, foremost by Marx. “The standard Marxist account of modernity,” Pippin says, “is that it is the unleashing of an unsustainable form of life, capitalism.” Nietzsche and Heidegger, meanwhile, saw modernity as a kind of human regression, a spiritual loss. Such criticisms, Pippin argues, mischaracterize both Hegel and modernity. Their “sweeping rejection” overlooks what he sees as the movement’s possible advances. The rise of modern natural science, liberal democracies and rights protections, and the “beginning of the end of religious warfare” all resulted from the modern revolution. And these developments “don’t have the necessary fate assigned to them by postmodernism”—the school of thought, beginning in the 1970s, which claimed that modernity had ended and a new era had begun, that the promises of enlightenment had not been fulfilled. Postmodernists, Pippin says, are too quick to declare modernity dead. “Before we worry about the legitimacy of the modern project, we have to understand what it is. We’re just now beginning to understand what the modern world meant for humanity. It’s far too soon to be making apocalyptic pronouncements about its demise, its role in imperialism, and so forth.” Hegel’s modernity, according to Pippin, falls somewhere in between conformity and self-determining individualism. Hegel was the first thinker to consider art, literature, politics, and religion as aspects of philosophy, all with the same goal: a complete self-knowledge about what it is to be human. And in Hegelian fashion Pippin—who’s already explored the literature angle with Henry James and Modern Moral Life (Cambridge University Press, 2000)—plans to tackle modern art from such a philosophical perspective. “What happened in visual art in the 19th century?” he asks. “Why did figurative art cease to become the standard and avant-garde or conceptual experimentation become the norm?” Again, Pippin notes, “Most philosophers wouldn’t think of that as a philosophical question but rather one for art history.” For Hegel, though, art, along with religion and politics, were part of a “vast historical, systematically connected narrative.” When Pippin returns to Chicago he plans to apply this approach to post-Hegelian art, writing a book called After the Beautiful. It’s one project he’ll pursue with a $1.5 million Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Distinguished Achievement Award. The grant gives him three years to fly in speakers, hold seminars, and plan Chicago conferences and lecture series on his chosen subjects. “In a way I’ve become my own little foundation.” He also plans to write The Erotic Nietzsche: Philosophers without Philosophy. As the “prophet of the demise of the modern, enlightenment form of life,” Pippin says, Nietzsche declared that liberal-democratic institutions were failing as a way of life because of “the failure of desire”: liberal-democracies, he believed, could not excite and sustain the allegiance necessary to be reproducible. “I disagree with him, but I’m interested in the framework of the question”—that is, given the problem of desire as a shared enterprise, perhaps even a shared fantasy, under what circumstances does it originate, and how does it die? But first there’s that book on Hegel. —A.B.

|

|

Contact

|