|

|

|||||||||

|

In a fascinating chapter of Mesmerized: Powers of Mind in Victorian Britain (Chicago, 1998) associate professor of history Alison Winter, AB’87, details how mesmerism was commonly used to treat chronic illness. Originally called “animal magnetism” and later “mesmerism” after its creator, Franz Anton Mesmer, the practice required the mesmerist (usually a man) to make “magnetic passes” over his subject (usually a woman) to bend her to his will. These passes—long, sweeping hand gestures over the surface of the subject’s skin—were close enough that each felt the body heat of the other, without actually touching. In the chapter, “Emanations from the Sickroom,” well-known Victorian intellectuals—and invalids—including poet Elizabeth Barrett Browning, mathematician Ada Lovelace, and journalist Harriet Martineau describe mesmerism’s power. Their accounts are so persuasive that a reader could be sucked into the Victorian mindset, convinced—for a while, anyway—that the technique had curing ability.

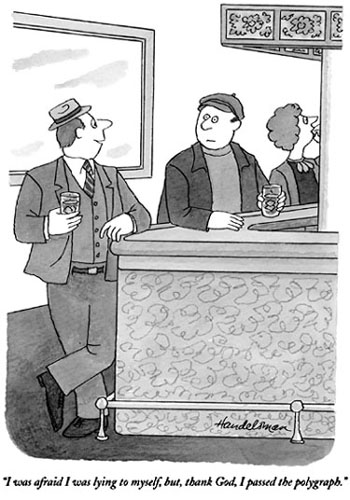

But Mesmerized is not at all concerned about whether mesmerism “worked.” Instead Winter, who earned her Ph.D. at the University of Cambridge in 1993, reconstructs the Victorian debate over mesmerism’s validity—a challenging task, given that when she started her research she considered the practice “totally ridiculous,” though as a historian she suspended such judgments. Taking a similarly nonjudgmental approach to her current project, Winter is exploring the notion of a “truth serum” or “truth technique.” Last year she received a Guggenheim fellowship to support her research, which traces the science of memory from the 19th century to the present. Her truth-sera account begins in the 1910s with Robert House, an obstetrician in Ferris, Texas. Like many country doctors of the time, House used scopolamine, or “twilight sleep,” to ease labor pains. He claimed that his patients, though seemingly incapacitated by the drug, could answer questions—and always spoke the truth. The example he gave to support his claim was hardly an issue worth lying about: when House asked the husband where the scale was (to weigh the newborn), he didn’t know, but the mother heard House and answered correctly that it was hanging on a nail in the kitchen. “Maybe she actually said something that was more of a revelation,” Winter speculates, “or maybe she said other stuff too,” but House was too decorous to include it in his account. Although truth sera have been associated with hostile police interrogations since the 1930s, House publicized his research for the opposite purpose: to exonerate the innocent. Convinced that the justice system was deeply corrupt, he gave “scopolamine interviews” to suspects protesting their innocence. Most courts rejected these interviews, which presented a “neat circular issue,” Winter explains. For the truth-sera testimony to be reliable, it would have to be given involuntarily; but involuntary testimony would violate the legal principle against compelling a suspect to testify, even in his own defense. Next Winter traces the psychiatric use of two synthesized “truth drugs,” sodium amytal and sodium pentothal, which made patients more communicative. During World War II these drugs were dispensed to treat a mental condition known as “battle exhaustion.” In a classic catch-22, military doctors were taught that the drugs were so powerful, patients who didn’t recover must be faking and were sent back to the front. If the treatment worked, the soldiers were considered better and also were sent back to the front. After the war the applications for these drugs changed yet again, when CIA researchers experimented with a “lie serum”—a “technique for fabricating memory and even an understanding of one's self”—to brainwash subjects. Winter’s chronological survey, which includes “truth technologies” such as polygraphs and forensic laboratories, concludes with the controversy over recovered memories—from eyewitness testimony to adult memories of childhood abuse—a subject that indirectly inspired the entire project. At the California Institute of Technology, where she taught from 1994 until 2001, Winter was often asked by her scientist colleagues to explain mesmerism in contemporary terms: “Was it like hypnotism is now?” “But hypnosis doesn’t have the broad cultural resonance that mesmerism had in the 19th century,” she says. The closest analogue, Winter decided, was the recovered memory debates, which were “incredibly important in the ‘80s and the early ‘90s.” Ferreting out the truth about truth technologies has been more difficult than Winter anticipated. Partly she was spoiled by the ease of researching the Victorians, who were obsessed with “documenting their own lives,” she says. Many wrote daily letters, preserved the letters in books, and willed the books to descendants. The increasingly tight control over contemporary U.S. government documents makes research more difficult: some CIA files that were once in the public domain, for example, have since been quietly withdrawn. —Carrie Golus, AB’91, AM’93

|

|

Contact

|