|

|

|

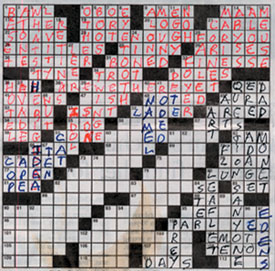

Competitive crossworders do it in ink. So can the

amateurs—taking pleasure in seeing where the words go wrong.

It’s true I’m a two- or three-grid-a-day player, downing the Tribune’s puzzles with the morning coffee and saving the New York Times for an end-of-day soporific. And it’s true I can recite the genre’s stalwarts, those odd, consonant- or vowel-heavy words that are money in the bank for Reagle and his fellow constructors. When, for example, was the last time you came across an etui or an ani, or even an SST, outside the friendly confines of a crossword grid? But I’m no Bill Clinton. According to Reagle, the former president is said to complete the Times Sunday challenge in ink, mistake-free, in about 20 minutes. Reagle adds that one of Clinton’s tricks is to use a lowercase e, its quick up-and-down curve shaving valuable nanoseconds off the time needed to pen the uppercase E’s four separate strokes. Still, like those hapless American Idol hopefuls who, because they can sing along to karaoke, dream of becoming the next Britney Spears, I’ve had moments—moving from 1 through 72 Across with hardly a bump, returning to 1 Down and filling in the vertical blanks nonstop—when it seemed possible to take it to the next level: to time myself. The second the clock radio gets pressed into service as stopwatch, the puzzle gets harder. Too many white squares, too few black boxes. A Sunday theme whose underlying wordplay doesn’t click, or a “well-known” quotation that spreads incomprehensibly from row to row. Then the puzzle morphs from fun to nightmare marathon, with me in ink-stained sneakers, straining forward but falling behind. So I’ve learned to take solace in hitting the wall. I love the way the same clue (a five-letter word for “lollipop cop”) that draws a blank at bedtime (“nanny”?) jumps out the next day with the clarity of a Monday morning quarterback (“Kojak”). Although it would be nice to have the right answer pop up precisely at the moment it’s needed, it’s comforting to know that my mental storage operates much like my bedroom closet: I may not be able to find that sweater today, but I know it’s in there somewhere. In the same way, a wrong bet placed on an ambiguous clue (is rain being used as a noun or a verb?) can be seen as a glass-half-empty defeat (a superimposed letter in all its proof of imperfection) or a glass- half-full advance (one step nearer the solution). There’s another reason to consider

the race as important as the finish line. A University of California

at Los Angeles study suggests that regularly working one’s

way through a crossword puzzle (or engaging in other forms of intellectual

stimulation) may stave off the onset of Alzheimer’s disease.

You can’t say that about watching American Idol.—M.R.Y.

|

|

phone: 773/702-2163 | fax: 773/702-8836 | uchicago-magazine@uchicago.edu