|

|

|

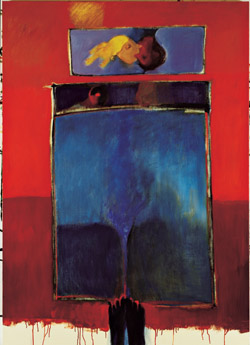

Open Mike Painter John Ransom Phillips, AB’60, PhD’66, takes a peek under the sheets in Bed as Autobiography. New York artist John Ransom Phillips remembers when he first started painting at 6 or 7 years old, about the age when “adults usually tell children not to paint trees that are blue, that trees are actually brown and green.” He found himself working “with a sensitivity to my own world, which I saw in conflict and contrast with the world surrounding me.” He’s long since escaped his childhood authority figures, but he’s still developing his own universe (also see pages 54–55). In his latest collection, published by the U of C Press, he tackles beds and all the activities they host, straying into themes of memory, past lives, and self-expression.—A.L.M.

On painting: I think that in my own experience I always start with an idea and the idea dictates the color, the composition, the space. The whole fabric of the painting evolves from the conception. I’m not at all a painter like Monet, who’s very much sensitive to the nuances, say, of light on the surface of a wall, and that becomes the subject, that becomes the idea of the painting. He starts with the sensuous image and then he develops the conception from that. ... From the concept, I then see the image, and when I see the image I see the actual color of the sheets, the color of the blankets, the pillows, I see my mother and father’s head and hair, and I see my own flesh. On beds: I began to think about the crib as a place, and I began to think about conception and the embryonic sac as a place that’s also like a bed. ... Then I began to think about my own bed as a place where you can dream, you can read, you can make love, you can do all kinds of things. I began to see that that could be a great unifying element in the series: the bed as a place in which the fundamental rights of passage take place; from life to death and, in my case, you even move on with other lives. But even in this life it’s where you were born and how you grow up and how you experience life, and [life] in its fullest is frequently experienced in the bed. In fact, even a casket is rather like a bed, isn’t it? On past lives: I’ve always felt a certain pull, physically a pull, when I’m in certain places or I meet certain people, and I never really examined it much until I started really exploring the possibility of having lived before. ... The whole purpose and capacity of getting back to previous lives is that they have lessons for this life. This is the important life—the life that we’re living. ... I don’t think that in the art world today, for example, past-life regressions and the expression of feelings are necessarily desirable subjects. And despite that, I have persisted in the objective—the end of my painting is the communication of feelings coupled with a vision about lives lived that have appropriate and important lessons for me in this life. So if there’s any lesson, it’s to be true to my vision. What’s next: I’m working on a new series on heaven, and heaven for me is here, on this world, now, and it’s when we are connected with other people and with this planet. And, by the same token, hell is when we feel disconnected or alienated or separate. |

|

phone: 773/702-2163 | fax: 773/702-8836 | uchicago-magazine@uchicago.edu

Arts

& Letters

Arts

& Letters