|

|

| Spy guy After 30 years with the Central Intelligence Agency, Richard Schroeder, AM’65, PhD’75, bids his secret identity adieu.

He doesn’t stand out in the International Spy Museum crowd. Dressed in typical Washington, DC, business casual—herringbone sport coat, brown slacks—the 61-year-old gentleman sits quietly through an introductory film in the auditorium’s back row. Moving into the gallery space, he views one exhibit after another, maintaining a low profile among the tourists and local visitors. But listen as he inspects James Bond’s Aston Martin DB5 on display. The license plates are about to rotate, he predicts. Within seconds the plates flip on cue, changing their numbers. His own work car, he admits, lacked the spinning feature. As far as fictional spies go, he says, “I like Bond, but no blond has ever tried to seduce me.” Now heads are turning. Who is this guy? His commentary’s better than the museum captions. He’s a guy who describes Psychology of Intelligence Analysis as a “wonderful little read,” whose regular vocabulary includes phrases like “settle on a rendezvous,” whose résumé boasts top-secret clearance, and who long kept his profession from his friends. Meet Richard Schroeder, AM’65, PhD’75, an intelligence officer with the Central Intelligence Agency for 30 years, including several assignments abroad during the Cold War. “Intelligence officers have to steal secrets, record secrets, and get secrets...back to headquarters,” Schroeder explains. “A lot of what you’re doing is kind of like magic.” Since his September 2003 retirement, he has applied his espionage expertise as a CIA consultant, a professor, and a member of the new Spy Museum’s board of advisers. “For my entire career I was undercover, so I couldn’t really talk,” he notes. Lips now unsealed, he can share some stories, deleting details such as his specific location. So in late October we rendezvous in DC. Schroeder picks me up outside Dupont Circle’s Tabard Inn. I climb into his shiny black Miata. With his salt-and-pepper hair, mustache, and beard, he’s more Sean Connery than Pierce Brosnan.

Maneuvering us out of the city and toward the CIA’s Langley, Virginia, campus, he bemoans the barricades blocking Pennsylvania Avenue. “You got all the cop cars and the darn security,” he complains, sounding like any disgruntled driver. That’s part of Schroeder’s magic—he seems an everyman, just another husband, father, civil servant working for some indistinguishable government agency. Even his son was shocked to learn the truth as a teenager. His reaction, Schroeder recalls, was “hysterical laughter. Who imagines daddy’s a big-time CIA guy?” Schroeder himself didn’t imagine such a high-risk future. In fact, he planned to enter academe. Growing up in Massachusetts and Ohio, scholarly surroundings were the norm with a German-professor father and a librarian mother. Languages were big, and Schroeder spent a college summer on an immersion program in Germany. After graduating with degrees in French and history from Kent State University, he headed to Chicago on a Woodrow Wilson fellowship, an honor that earned the Army ROTC member a four-year deferment. Schroeder put his military respite to good use, both in and out of the classroom. By his third year in Hyde Park he had completed his master’s in European history and married Leah Elizabeth Webb, another Woodrow Wilson fellow. Leah, AM’68, got her master’s in political science, and he began researching his doctoral dissertation. Before he could finish, time was up. Commissioned as a second lieutenant in Army intelligence, Schroeder first had to attend infantry school. Thanks to his history background, he next landed a DC post, predicting what various countries would look like in 2000. Life was good. Leah was working on Capitol Hill; they enjoyed the city. But it was 1969. By the following January, he had shipped off to Vietnam. Picked to do secret analysis of Vietnamese activity in Laos and Cambodia, in collaboration with the CIA, he made it through his tour physically unscathed. When Schroeder got home in fall 1970, however, he and the country had changed. The Kent State riots had taken place, with four war protesters killed at his alma mater. Society seemed polarized. Furthermore, “the bottom had fallen out of the academic market, and there were no jobs,” he recalls. He returned to his dissertation and applied to the CIA, figuring he’d produce analyst reports similar to his Army ones for “the premier organization” in the intelligence community. In 1972 he entered the agency—a change in career path he could tell only his immediate family about. It proved a good fit. “I felt it was much more concrete and constructive,” he says. “Research was too theoretical anyway. Instead of a desk person I’m a street person.” Formed in 1947 from the Office of Strategic Services, the CIA was designed as an independent federal agency tasked with supplying national security intelligence to senior policy makers. Identifying potential threats and then digging for information, employees work in three directorates: intelligence, science and technology, and operations. Schroeder chose to pursue operations, which focuses on information gathering, often abroad. As an officer in its clandestine service his main responsibility was recruiting agents—foreigners who provide secrets about their countries. He was trained in “spotting sources, eliciting information, persuading people to cooperate, writing reports.” He compares the position’s duties with those of an investigative reporter. “Only, the thing is, if your source gets caught, he gets thrown into a shredder or an oven.” He learned the espionage craft on his first overseas tour in Western Europe in 1975, the same year he earned his doctorate in modern military history. Leah, leaving behind a representative’s chief-of-staff position, and their new son, Michael, came along. Schroeder explains, “I told friends I was a member of the local diplomatic establishment in the town, dealing with the host country.” He had to wear two hats, working late into the night. During the day, he says, “you stamp visas, do diplomat things, go to cocktail parties.” After hours he’d do spy things. “Your real job is meeting with agents.” Against the backdrop of the Cold War, “the hard targets were the Russians, Eastern Europeans, Chinese, and North Koreans,” Schroeder says. “You were really out there on the front lines.” The agency, he adds, expected spouses to join the fight, sometimes putting their careers on hold. “When we got to a new post,” Leah recalls in a recent e-mail, “I had to ‘reinvent myself,’ as Rick is fond of saying.” She helped maintain his cover story, volunteering and entertaining. He laughs, “I can remember showing a Russian KGB officer All the President’s Men.”

After three years his family headed home in 1978. Leah took up lobbying; he supported officers abroad from CIA’s Langley headquarters. He told neighbors, “I’m working for the U.S. government, and I do foreign affairs.” A two-and-a-half-year European tour followed in 1982, with Leah and Michael in tow. Next Schroeder managed the headquarters branch of overseas programs; Leah became a trade association’s vice president for governmental affairs. When an opportunity arose for him in 1990, they packed their bags again. One year later the Soviet Union collapsed. Michael’s high school closed. The local movie theater and Burger King shut down. The American community left town. While Michael finished up at a Maryland boarding school, Schroeder and Leah remained so he could oversee a field office. Three years later they moved back too. “I decided I’d like to do something different,” he says, and in 1995 he accepted a colleague’s offer to work at the agency’s Office of Congressional Affairs. “I’d always been interested in Congress,” he explains, “because my wife had been on the Hill.” He signed on as one of two operations officers serving as liaisons to the Senate and House committees that monitor the agency. Not long into the job the CIA came under investigation for its ties to a Guatemalan colonel implicated in a U.S. citizen’s death. Schroeder had to coordinate hearings probing agency activity in Central America and write the CIA’s official record of such inquiries. Over the next three years he handled briefings on the Middle East and Europe, POW/MIA cases, and counterterrorism. In 1998 Schroeder became deputy director of the CIA’s Center for the Study of Intelligence, making him one of about 100 top mangers in the agency. The center’s scope includes publishing journals and books, declassifying historical documents, sponsoring conferences and seminars, and placing officers at universities. “That got me back, for the first time in 20 years, in the academic atmosphere.” The job also put him at the helm of the agency’s museum, which houses its permanent collection of artifacts and photographs. From there Schroeder rounded out his career, becoming CIA chair and political-science professor at the National Defense University’s Industrial College of the Armed Forces. He loved academia and in 1999 picked up an adjunct position at Georgetown University’s Edmund A. Walsh School of Foreign Service, teaching courses on strategic intelligence and technology. Having come full circle, he decided to stay at Georgetown after reluctantly handing over his staff CIA badge—a transaction the agency requires when officers turn 60. He confesses, “I was sad to retire.”

For Schroeder, life as an ordinary guy is hardly humdrum. He had long promised his mother he’d write for her series Missouri Heritage Readers, cultural books geared to adult-literacy education. Drawing on his military-history background, his contribution, Missouri at Sea (University of Missouri Press, 2004), recounts warships named after the Show-Me State. Then there’s the International Spy Museum, which he helped get off the ground by providing developers and staff with strategic advice on exhibition concepts, themes, and programs. He continues to advise the museum on new exhibits. He regularly regales his Georgetown students with spy stories and espionage tips. And he travels with Leah, now a private school’s development director, and Michael, formerly an Army military policeman and now studying architecture at Northern Virginia Community College. Still, when the outside world seems a little lacking in excitement, Schroeder can zip over to the CIA. That’s the plan today, and we’re minutes from the agency museum. Closed to the public, he describes it as “the best museum you’ve never seen.” Flashing his green badge (and relaying my Social Security number), he rolls his two-seater through the gate. As a consultant, Schroeder returns regularly to the leafy campus. “In the ’90s we thought we could afford a much smaller intelligence community,” he explains. “After 9/11 the demand exploded, and there weren’t any experienced people. Suddenly you had a small, overstretched agency,” and retirees were called in. Of course, consulting isn’t the same as being a big-time CIA guy. While parking Schroeder’s mood turns nostalgic. “I stayed to the last possible second,” he says, then perks up to share an inside joke. His vanity license plates may not flip, but they do offer a clue to his agency ties, reading OXCART, the code name for the original supersonic, high-altitude reconnaissance aircraft. The CIA developed the spy plane before the Air Force rechristened it the SR-71 Blackbird.

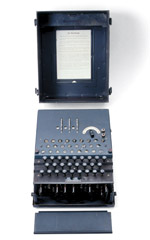

We pass through the historical entrance and more security. Inside the museum, surrounded by tools of the trade, Schroeder launches into his lesson. “We tend to have small teams of people working in shops around the world,” he explains. “We’re the guys out there trying to get the information that you can’t get any other way.” They rely on high- and low-tech gadgets. In display cases he points to items straight from the trenches: a compass masked as a button, a camera hidden in a matchbook, playing cards with a concealed map. “Another way you can steal secrets is by listening in,” he says from experience. For example, there’s a woodblock—“the kind of thing I’ve used in the field”—that officers stick under a desk or a chair. Blending in with the furniture, the battery-operated device has a receiver and a transmitter. “You send a signal to turn it on.” Next on his useful-equipment list is a briefcase scanner that copies secret documents on the go. Scores of artifacts later, we find ourselves out in the hall. It’s lunchtime, and Schroeder spots familiar faces as we stroll around the CIA, slowly making our way to the exit. He waves or stops to shake hands with students and former colleagues. One tall man, a senior analyst, briskly walks the other direction after learning I’m a journalist. Perhaps joking, he states, “You don’t know me.” These days Schroeder’s past is out in the open, his cover pushed back to when he joined the CIA, meaning his secret identity is no longer secret. Telling friends the truth, he recalls, “most of them said, ‘Oh, I always knew that.’ Of course most of them didn’t.” Leah still finds divulging the secret difficult: It “became so second nature to me that when he became ‘overt’ and could say where he worked, I still had great difficulty doing it, and I absolutely could not write it in this e-mail!” The contrast between then and now is illustrated in the difference between the agency’s museum and the public one downtown, where we head next. For starters, the International Spy Museum houses Zola, an upscale restaurant that, unlike the CIA cafeteria, is a place to see and be seen. We slide into one of the booths, whose red leather back extends to the ceiling. “This looks like an agent meeting,” museum executive director and former operations officer Peter Earnest says, stopping by to visit. The comment prompts the retirees to reminisce. They had met with agents in restaurants. One kept his notebook in his lap, the other on the table.

The discussion turns to the current state of affairs: what’s good to eat here. Both on the South Beach Diet, they recommend the chicken salad and the burger sans bun. Earnest then leaves us to our meal, but not before underscoring Schroeder’s contribution to the museum. “He has a wonderful command of intelligence history—not only history, but how it works,” he says. Of the board members he’s best “able to put [artifacts] in context.” The skill came in handy as the museum’s investors looked for experts to ensure they presented espionage in a thoughtful manner, separating fact from fiction. Following a briefing at the CIA, they invited Schroeder to serve as an adviser. “I started working with them when this place was rubble.” Opened in 2002, the 68,000 square-foot museum revitalized F Street, in DC’s historic Penn Quarter. Its permanent collection contains many items similar to those in the CIA’s modest galleries, but interactive exhibits and special effects create a theme-park feel. As we check out the displays after lunch, flashing lights reflect off Schroeder’s glasses. With plenty of pop-culture references from Get Smart to James Bond, the place seems geared to the MTV generation (founder Milton Maltz also helped create the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and Museum). But here real-life spies intrigue, and a crowd fills one of the last exhibit rooms, listening to true stories of double agents. Bad seeds aside, Schroeder defends the CIA against criticism and denounces those who reveal officers’ identities for political reasons, as happened to Valerie Plame. He believes President Bush’s call for creating a director of national intelligence—part of a post-9/11 revamping effort—is unnecessary. “We already have one,” he says of the agency’s director of central intelligence who also has limited control over the larger information-collecting community. Still, he knows the CIA and espionage have their faults: “It’s never perfect because it all deals with humans.” He’s not above wearing such a message on his sleeve at the agency’s gym—“My friends went to Iraq to look for WMD and all they found was this lousy T-shirt.” It’s a fashion statement, he concedes, not all his fellow exercisers appreciate. To minimize mistakes and to make room for new recruits, intelligence officers eventually retire. For Schroeder, it’s just as well. “I don’t want to go out now and stand on the corner in the rain at midnight, meeting an agent,” he admits, then zooms off in his sports car to rendezvous with Leah in the Virginia suburbs. Espionage equipment photographs courtesy International Spy Museum. |

|

phone: 773/702-2163 | fax: 773/702-8836 | uchicago-magazine@uchicago.edu