|

|

|

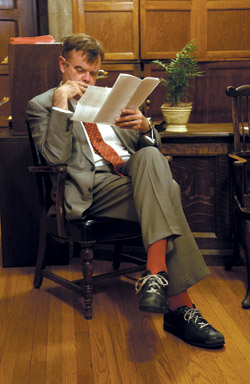

Well, look who’s coming through that door... He wore his trademark red socks, but Prairie Home Companion host Garrison Keillor was in a decidedly blue mood when he arrived at Rockefeller Memorial Chapel November 3. “I am a Democrat,” the public-radio icon told the near-capacity crowd. “I am a museum-quality Democrat, and I have spent my time this morning crouched in a fetal position.”

“But I’m over it,” he announced a few minutes later, turning his attention to the reason for his Chicago visit, part of a nonpartisan celebration honoring South Side native Gary Comer and his wife Frances, whose $21 million gift helped build the University of Chicago Comer Children’s Hospital, which opens in January. Founder of catalog giant Lands’ End—a Prairie Home Companion sponsor—Comer, said Keillor, has two great philanthropic interests: abrupt climate change and the city of Chicago. “When I heard that he was supporting a children’s hospital,” he deadpanned, “I thought it must be a hospital for children who had suffered from abrupt climate change—that is to say, winter.” With that, the Minnesota raconteur was off, rambling through memories of childhood injuries and remedies (a fall from a haymow, the application of Vaseline). “Somehow,” he told the Baby Boomer audience, “we survived the trauma of childhood,” only to experience the trauma of parenthood. “You hold this small, naked person in your hands, and, before you hand it over for its soles to be pricked, your own soul is pricked by the thought that a person has come into the world that you now love more than yourself,” a person for whom “you would run into shark-infested waters.” Rescuing the sentiment from cliché, he drawled: “One more reason to live in Minnesota.” Most parents don’t have to face sharks, but as Keillor’s stories of his young daughter’s medical emergencies made plain, they nevertheless end up doing things for their kids they wouldn’t dream of doing for anyone else. So what keeps them going? “Nothing you do for children is ever wasted,” he said. “Parents live on this belief. So do schoolteachers. And so do the people who endow children’s hospitals.” Again he offered a story. A few weeks earlier he’d emceed a University of Minnesota event to mark the 50th anniversary of the first open-heart surgery using cross circulation. At dinner the men and women who’d had the operation as children were asked to stand. As they stood there, “short, tall, slender, heavy, people from all walks of life,” he confessed, “you wanted to ask them, ‘What kind of life did you have, this miraculous life that you were given?’ And then you thought, ‘Life itself is good enough, just the gift itself.’” The parents of some of those grown-up children had practically camped outside the hospital to secure that gift, and “all of the great things” that come out of the Comer Children’s Hospital also “will be in great demand,” Keillor said, his mood shifting back to blue as he considered the relationship between supply and demand. When it comes to the national allocation of health-care dollars, he argued, “we have extended our own golden years rather than save the lives of children.” But it was getting late. “I think,” he concluded, looking up at Rockefeller’s Gothic arches, “we should close this by singing. We get so few chances to sing.” Hand held chest-high, he demonstrated the key of “about there,” then led his choir through two verses of “We Shall Overcome.”—M.R.Y. |

|

phone: 773/702-2163 | fax: 773/702-8836 | uchicago-magazine@uchicago.edu