|

|

|||||||||

|

Curing the world, one epidemic at a time A Chicago-trained physician

applies his public-health expertise globally, tackling TB, AIDS,

and even youth violence.

Violence didn’t concern Slutkin while growing up in Chicago’s Albany Park and Rogers Park neighborhoods, or as an undergraduate at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, where he studied physiology and behavioral psychology. Enrolled at the Pritzker School of Medicine (“the dean told me that I was the first applicant from the Chicago Public Schools in many years”), in his first week he passed a murder site riding his bike back to his 53rd and Harper basement apartment. After med school he interned at the University of California, San Francisco. Offered the chief residency there in 1979, he first took time off to travel through Africa. “It was primarily adventure, curiosity, and basic interest in the continent,” he says. About ten friends—including two doctors, two mechanics, and “a couple of people who knew their way around”—rented a truck and spent nine months camping from northern to southern Africa. He saw “extraordinary poverty,” he says, and a “prevalence of illness beyond anything we’d ever seen.” The experience inspired him to take an infectious-disease fellowship after his residency. He worked part time for the city’s tuberculosis program, and when the program’s director retired in 1981, Slutkin, at 31, replaced him. “San Francisco had the highest rate of TB in the country by far,” he recalls, “and we had an epidemic on our hands,” mostly concentrated among Vietnamese refugees. “Surrounded by some really good people who could guide me,” Slutkin tried new approaches to the disease. His team kept personal tabs on all active TB patients, providing “directly observed therapy,” or actually watching people take their medication. They also doggedly treated multidrug-resistant patients, although the going theory was that such patients were less contagious. Short-course chemotherapy for TB, also new at the time, proved useful. And they trained Vietnamese, Cambodian, Laotian, and Central American community members to find and care for TB patients—an outreach approach that would be vital to his future work. Within four years the epidemic was curbed. In fact, of the dozen U.S. cities with exploding TB cases, San Francisco was one of the few to reverse the trend. Slutkin’s approach and the city’s TB training program became models. During this time Slutkin also made a few trips, with Medical Volunteers International, to Somalia, where 1 million refugees from the recent war with Ethiopia lived in 40 camps. After doctors stabilized acute diseases such as malaria and pneumonia, TB emerged as the dominant problem, and Slutkin helped set up clinics at the camps. But on a 1983 return flight to San Francisco, he found himself wondering why he was going back. By then San Francisco had only 500 TB cases, almost all on treatment, and Somalia had 25,000 to 50,000 cases, with maybe 4,000 treated. “It seemed to me that the job in San Francisco was done,” he says, “and the job in Somalia was undone.” So in 1985 he moved to Somalia. He lived in an aqal, a stick and dirt hut, and slept on the roof—to escape the heat and to see the stars. Six days a week he struggled to procure international funds and supplies and to persuade the refugees, who had little health-care knowledge, to visit the clinics. Some officials also seemed out of touch. When a cholera epidemic complicated the doctors’ efforts, Slutkin says, “a general offered to shoot all cholera patients.” Slutkin kept a journal of the daily, horrific deaths—someone drowned in sand, a child eaten by a shark. “I would not go to sleep at night until I had written it all out,” he says. He’s never reread it. Still, his international team managed to create a model refugee system. With six doctors, they trained 3,000 to 6,000 refugees in patient care. They stopped the TB. But psychologically, he “had to leave.” In 1987 he moved to Uganda as one of the first eight people to work on the World Health Organization’s (WHO) global AIDS project. Assigned to Uganda and 12 surrounding countries, Slutkin devised a method to track AIDS trends: at neonatal clinics he separated the women’s blood samples by age group, monitoring HIV trends in each group. His sentinel surveillance for HIV is still used globally to estimate AIDS infections. He also set up health-education, counseling, and testing programs, focusing a bit on condom distribution but more on norm changing. “Uganda was pretty much a stick-to-your-partner program.” And it worked. Uganda became the only African country ever to reverse its AIDS trend. The surrounding countries, Slutkin says, were “on their way,” but the program “basically stopped” with early 1990s WHO leadership changes and little international support. Frustrated, Slutkin moved to Washington, DC, in 1994. But he struggled internally over his next mission. After ten years of fighting critical shortages abroad, he says, he “had no interest in being a physician” in a country with so many doctors that they “fought over patients.” But one U.S. issue caught his eye.

Newspaper stories told of “children shooting other children

with guns. Now this was actual insanity,” he says, “that

a 12-year-old would shoot a 15-year-old, and that it was really

common.” He asked numerous cities’ officials and organizations

about their strategies to face such violence. “I wasn’t

hearing the kind of thing that we would think of at World Health

as a strategy. I was hearing about programs, I was hearing about

elements, but nothing that could actually add up to large-scale

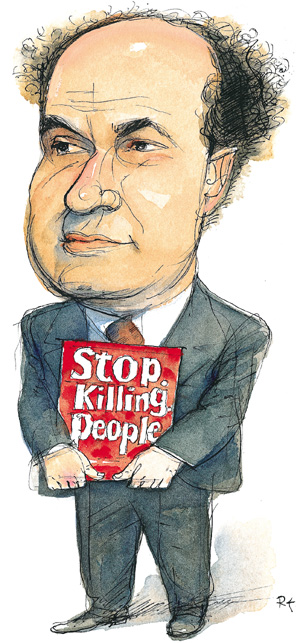

change.” So in 1995 he moved back to Chicago, which had more killings in 2001 than any other U.S. city. As a professor at the University of Illinois at Chicago’s School of Public Health, he began the Chicago Project for Violence Prevention. For five years he secured foundation, community, and government partners, researched tactics, and recruited outreach workers. In 2000 CeaseFire, the organization’s implementation arm, entered its first neighborhood, the West Side’s Garfield Park. CeaseFire gathers former gang members and drug users for outreach, builds trust in communities by helping residents with job, school, or money problems, and posts signs with blunt slogans—“Stop. Killing. People.” reads one. If CeaseFire workers learn that a teenager is planning to retaliate for his sister’s recent shooting, they’ll confront him, asking, “What can you possibly be thinking? Don’t you know you’re only going to hurt your mother even more?” It can lead to loud cussing matches. “It isn’t pretty,” Slutkin says, “but a lot of health care isn’t pretty.” Shootings in Garfield Park dropped

67 percent the first year, and months went by with no shootings

at all—unheard of at the time. Now in more neighborhoods,

CeaseFire averages 45 or 50 percent drops. Other cities are knocking

on Slutkin’s door: Baltimore, New Orleans, Los Angeles. And

the program, Slutkin believes, could expand internationally, wherever

“armed young men in disaffected, marginalized circumstances

have learned violence.” Once again, he’s created a model.—A.M.B.

|

|

Contact

|